Type of Project: Building History/Recordation

PRO Services: National Register of Historic Places Nomination

Commencement: 2014

Status: Listed January 28, 2013

What looked like an eyesore to many viewers looked like a potential hub for creative uses to developer Eric Friedman. Friedman enlisted PRO’s Michael Allen to draft a National Register of Historic Places nomination for the abandoned Alligator Oil Clothing Company Buildings. Allen’s investigation found that the Alligator buildings unfolded a web of corporate and architectural history — showing that one can’t judge a group of buildings by its graffiti (a constant presence here), or its fire damage (which led to demolition of a wing), or its building type (factories aren’t well represented in the local annals of the National Register).

Today, the complex awaits a larger redevelopment, but has been incrementally improved to house deconstruction start-up Refab, which has used part of the complex for storage and retail operations. Without Friedman’s interest, the historic factory complex may well have been demolished. In fact, the city wrecked the historic smokestack — which had partially collapsed, but could have been restored as a visual anchor — in 2009.

The Alligator Oil Clothing Company Buildings are located in what is now called the Bevo neighborhood of St. Louis at 4153-7 Bingham Avenue in the southern portion of St. Louis, Missouri. The complex consists of four buildings and the ruins of a fifth building. The two main buildings consist of a four-story reinforced concrete factory building (1918) and a two-story reinforced concrete office and factory building (1919). Both buildings were designed by architect Leonhard Haeger, an accomplished architect whose practice included the landmark reinforced concrete Pevely Dairy Plant. To the north of the first building building is a one-story flat-roofed non-contributing support structure dating to c. 1960. To the east there is also a one-story warehouse dating to 1959. Connecting the two main buildings are the ruins of the fire-damaged addition from 1943. The loss of the addition returns the plant largely to its pre-1943 appearance.

The Alligator factory building is one of only six identified St. Louis buildings built between 1900 and 1920 to fully expose its concrete structure on the exterior, making it an outstanding example of reinforced concrete industrial design in St. Louis. The second building is a good example of the more conventional local practice of employing brick face cladding in reinforced concrete industrial architecture. Together, the Alligator Oil Clothing Company Buildings embody the range of treatments of reinforced concrete industrial architecture employed locally between 1900 and 1940, when Modern Movement architectural practice led to greater experimentation with exposed concrete surfaces. The period of significance begins with the 1918 issuance of the building permit for the first of the two buildings and ends with completion of the second building in 1920.

With burgeoning rail access to southern and southwestern cotton markets, St. Louis thrived as a center of garment manufacturing after the Civil War. By the early twentieth century, the city had a diversified garment industry that included manufacturers of dresses, suits, coats and uniforms as well as related shoe and millinery concerns. Yet among the producers of garments, none in St. Louis specialized in rain-repellent outerwear until the Ferguson Waterproof Company was incorporated before 1911, which later reorganized as the Alligator Oil Clothing Company in 1916.

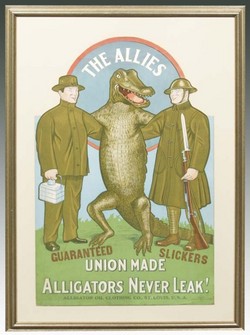

From 1916 through 1918, the company’s manufacturing took place in a two-story factory at 1118 S. Grand. World War I provided impetus for major corporate expansion and construction of the National register-listed plant. The United States Army purchased some three million Alligator raincoats for soldiers, according to an Alligator advertisement. All of these coats were made in St. Louis, and led to the company’s decision to relocate to a large, modern facility with sufficient capacity for large demand. The company’s new facility led to boastful advertising touting its wartime production and the assertion that Alligator’s coats were the only union-made rain gear in the nation. The company’s ads appeared nationally into the 1940s. In 1943, expansion of the plant led to Alligator opening New York and Los Angeles branch offices. During World War II, Alligator enjoyed substantial success as both a military and civilian supplier.

In 1966, clothing giant BVD, Inc. acquired Alligator, continuing production at the Bingham Avenue plant until 1971. In 1971, BVD sold the factory complex to Multiplex, Inc., a manufacturer of beverage dispensing equipment and water treatment systems for the foodservice industry. Multiplex left the plant by the late 1990s, and the buildings have been vacant since then.

Reinforced concrete frame construction appeared in St. Louis by 1900, used first for cold storage warehouse construction, but its use was not widespread until after 1905. Throughout the first decades of the use of reinforced concrete for industrial architecture, full display of the concrete structure on the exterior was rare, possibly due to the influence of the local brick industry. Yet local architects were quick to take advantage of rapid early advances in reinforced concrete technology in American architectural engineering. Two of the earliest industrial buildings in St. Louis to employ modern reinforced concrete structures came from prolific firm Mauran, Russell & Garden and are contributing resources in the Washington Avenue Historic District.

During World War I, around the time that the Alligator Oil Clothing Company Buildings were built, the nation witnessed construction of the largest functionalist concrete industrial complex built between 1900 and 1920. In March 1918, the United States Army commissioned architect Cass Gilbert to design a massive military depot and supply base in Brooklyn, New York. Gilbert’s design for the five million square foot complex turned reinforced concrete into both an expedient construction method and an aesthetic principle. In St. Louis, however, such open display of reinforced concrete structure would remain unusual even as World War I limited steel availability. Despite conservative architectural treatment of the form, the reinforced concrete daylight factory received positive local press.

Three years after completion of the new Pevely Dairy Plant, its neighbor across the street on Grand Avenue, the Alligator Oil Clothing Company, hired Pevely’s architect Haeger to design its new plant on Bingham Avenue. Alligator needed a large fireproof building with specialized production areas. Haeger designed the Alligator Oil Clothing Company factory to fully express its reinforced concrete construction. The building employs a structural system based on Turner’s “mushroom cap” system, and a daylight factory exterior fenestration pattern based on Kahn’s daylight factory model. Whether limited budget or artistic license led to Haeger’s decision to reveal the concrete structure on the exterior is unknown, but given the location on a secondary street the Alligator company may have felt that further expense on the façade was unnecessary.

With the exception of the presence of the 1959 addition and the loss of the smokestack, the current appearance of the plant is consistent with how the plant appeared prior to the construction of the 1943 addition. Through intact form, exposed concrete structural grid, sawtooth skylights and presence of steel sash windows, the original Alligator building conveys its historic use as a clothing manufacturing building. Its large footprint is consistent with the scale of garment industry buildings throughout the city, including around Washington Avenue downtown. The large floor plates with ample perimeter light aided the set-up of banks of sewing machines and work stations for clothing production. The P.D. George Company building reflects its historic use as an office, laboratory and production facility for varnishes and other by-products tied to the oil clothing process as well as part of the later expanded production of the Alligator Oil Clothing Company. Both buildings continue to clearly demonstrate the reinforced concrete structure that makes them significant works of local architecture.

National Register of Historic Places Nomination

Alligator Oil Clothing Company Buildings National Register Nomination