Location: Between St. Louis, MO and East St. Louis, IL

Type of Project: Section 106 Review

PRO Services: Adverse Impact Report

Commencement: 2012

Completion: 2012

In 2011, the Terminal Railroad Association (TRRA) obtained a federal grant to fund removal of remaining portions of the highway road deck and highway approaches to the MacArthur Bridge. The grant was governed by Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act, mandating review by both Illinois and Missouri preservation officials. On October 7, 2011, the Illinois Historic Preservation Agency (IHPA) sent a letter stating that the MacArthur Bridge was eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, triggering a Section 106 review.

In January 2012, TRRA engaged Preservation Research Office (PRO) determine whether the MacArthur Bridge met National Register of Historic Places criteria for eligibility, and to determine whether the proposed removal of the remainder of the road deck constituted an adverse impact. PRO determined that the bridge was eligible, but that removal of the already-compromised road deck would not adversely impact the historic character of the bridge or impede future National Register listing. PRO Director Michael Allen prepared the report with assistance from former intern Alyssa J. Stein.

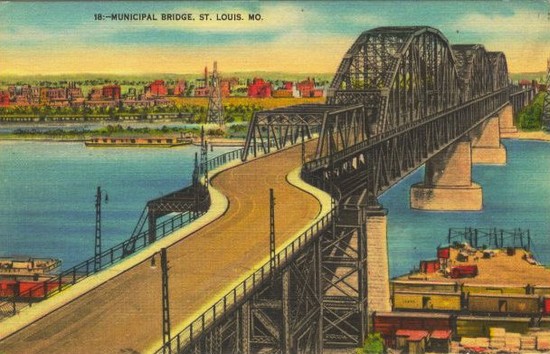

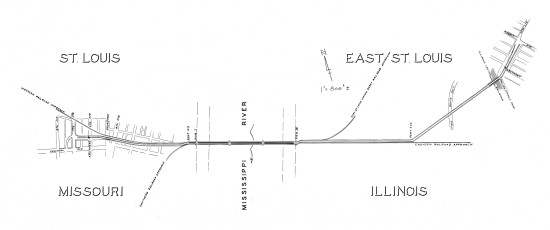

The MacArthur Bridge is a double-deck through truss bridge across the Mississippi River located south of the Gateway Arch at St. Louis, Missouri. The MacArthur Bridge and elevated track is the second-longest elevated steel structure across the Mississippi River. The bridge was built starting in 1909, and its vehicle deck opened upon completion of the western approaches in 1917 and its two-track railroad deck opened in 1930 after the south approach was completed.

The MacArthur Bridge and its approaches exemplify early twentieth century bridge construction and evince characteristics of the type of construction that define the visual form of the bridge system. The character-defining features of the bridge are those that are essential to its conveyance of the integrity aspects of design, materials, workmanship and feeling as defined by the National Register of Historic Places. These features need to be preserved to ensure that the MacArthur Bridge retains its integrity as a historic resource.

The following are 5 character-defining features of the MacArthur Bridge:

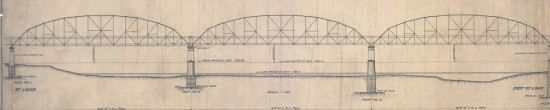

- Stone-Clad Piers: The four concrete piers with stone cladding that support the main span are essential to the bridge’s architectural character. The rusticated limestone facing and the profiles of the piers are integral to conveying the piers’ integrity.

- Three Through Pennsylvania Truss Spans: The three through Pennsylvania trusses identify the MacArthur Bridge as a large river crossing. These trusses are integral to the bridge appearance in their current form. The upper and lower chords, all struts, sub-struts, girders and pins are essential to the overall appearance of these trusses.

- Railroad Deck: The railroad deck over the continuous main spans defines the historic function of the bridge for railroad traffic. The structural floor beams, decking and railings that compose the deck element are all integral parts of this element.

- Railroad Approaches: The railroad approaches, including the western, southern, eastern, northern and south valley junction approaches are all integral to the railroad deck’s reading as a historic railroad crossing. These elements are secondary to the bridge character, but as part of the functional transportation system are significant elements.

- Structural Elements of Vehicle Deck: The structural elements of the road deck on the continuous main spans allow for the appearance of the original design of the bridge as double deck. The floor beams between upright struts are elements that define the intentional placement of a second deck on the bridge, and their maintenance allows for the MacArthur Bridge’s feeling, design, workmanship and materials to remain evident despite extensive alteration of the larger road system element.

The bridge was a significant road and rail bridge between St. Louis and the growing industrial city of East St. Louis to the east. From 1929 through 1955, the MacArthur Bridge carried United States Route 66, an association that clearly would make the bridge eligible for listing for that association alone.

The MacArthur Bridge is also the work of a master bridge designer, the firm of Boller & Hodge and its principal, Alfred Pancoast Boller. Boller was one of the nation’s premier designers of railroad river bridges, and his work spans the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The MacArthur Bridge was a rare project outside of the eastern part of the United States, and an undertaking that created the largest double-deck steel bridge in the world upon completion. While the record set by the MacArthur did not last long, the accomplishment is significant within the context of Boller’s career. The MacArthur is an important example of the late phase large-scale work of Boller, an established master bridge designer.

The MacArthur Bridge at St. Louis is a municipally-built double-deck highway and railroad bridge completed in 1917 as the longest single-span bridge over the Mississippi River with the longest simple spans constructed in the world. The City of St. Louis first approved bonds funding the construction of the Municipal Free Bridge, the original name for the bridge, in 1906. Engineering firm Boller & Hodge submitted plans for the bridge to the city in 1908, and construction began by 1909. The bridge consists of a main section of three through trusses of the Pennsylvania type, with separate road and rail approaches on each side of the river. The road deck opened in 1917, while the rail deck did not open to active traffic until 1940. In 1942, the city renamed the bridge for General Douglas MacArthur.

The reason for the bridge’s construction, railroad avoidance of the Terminal Railroad Association “arbitrary†at the Eads Bridge, was largely a moot point by the time that rail traffic utilized the bridge. However, the bridge crossing was necessary and well-travelled by rail and road. Road traffic increased when the bridge was included as part of U.S. Route 66 from 1929 through 1955. Yet the road deck’s deficient design—which included two quick turns at each end—made it a treacherous route, and the city closed the road deck in 1981. In 1989, in order to create the alignment for the MetroLink light rail system, the city of St. Louis swapped with the Terminal Railroad Association the MacArthur Bridge for the Eads Bridge. Since then, the Association has owned the bridge. The city has demolished parts of the road approaches. Today the active MacArthur Bridge is the 17th busiest railroad bridge in the United States.