by Michael R. Allen

In the last few months, two project proposals — one for an apartment complex at Taylor and Chouteau and another for a vague commercial development along Kingshighway — in Forest Park Southeast have emerged which are both grossly out of scale and character with the historic architectural character of the neighborhood. These projects exhibit deficiencies in consideration of scale, ratio of surface parking to building footprints, form and materiality. Together, these projects would overwhelm the accumulated urbanity of Forest Park Southeast with the fly-by-night aesthetics of American suburbia. After all, good urbanism needs more than development and density to thrive — it requires beauty and the human scale.

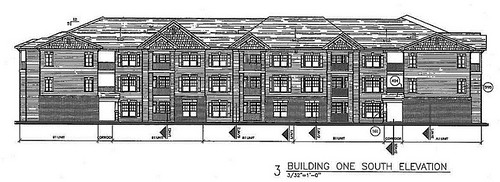

The first of these projects already has its first phase under construction. Tate Homes broke ground this year on “The Aventura at Forest Park,” a two-phase 202-unit apartment complex on Chouteau Avenue east of Taylor. The first building is under construction near the old Laclede Gas Pumping Station G, whose intriguing gasometer was sadly pulled from the city’s landscape in 2006. The second building will be built at the corner. Engulfing these buildings will be a whopping 371 parking spaces, built on surface lots rather than in a concealed structure. Tate Homes has built suburban projects including “Aventura at Indian Lake Village”, “Trails of Dickson” and “Turnberry Place,” among others. Hanley Station and Kirkwood Station Plaza are the developer’s better-designed, more urban projects.

Make no mistake: The designs of the apartment buildings are inappropriate to Forest Park Southeast, or any city neighborhood with accrued architectural fabric based on traditions of proportion, solid materials, color coordination and vernacular appropriation of style. The developers have a good program, and a bad design. These apartment buildings are of the same sort of confused, builders’ supply stock design as the apartment building at 3949 Lindell Boulevard that burned in a fire last month. These buildings are built with a material longevity of less than 50 years, and the exterior designs show that. Whatever stylistic details are tacked on are not sufficient to make these buildings beautiful.

Furthermore, the new apartment buildings do not address the intersection in any meaningful way. There are no storefronts at the corner, despite the fact that the other corners of the intersection have commercial storefronts. It is as if the developer took a building form designed to be places generically anywhere, and placed it on the site without contemplating the surrounding neighborhood fabric. In form and materials, the buildings make no attempt to harmonize. Architecture that fails to offer any commonality with its surroundings — setback, materials, use, form — is a failure unless the scale and treatment is monumental. Here, it is tepid even though the use and density of the project are good for the neighborhood. The failure is not the development, but the lack of mandated design standards.

There was a time when the intersection of Taylor and Chouteau was graced by buildings that offered qualities that fit the setting. Until demolition in 2005, the Walter Freund Bread Company stood at this intersection. The monolithic single-use bakery plant mitigated its bulk through use of human-scaled brick, use of relief to break up the expanses of wall plane and a harmonious proportion of solid to void in the wall plane. The Freund buildings were not exceptional early twentieth century industrial buildings, but fairly typical. Being typical meant that they were designed with the experience of the pedestrian in mind. These fireproof buildings were adaptable and should have been converted into housing. Yet the Forest Park Southeast Development Corporation chased the idea of new construction instead, and today that fantasy is becoming a lackluster reality.

A more spectacular blunder is the colossal commercial development that development company K2 has proposed for the western area of Forest Park Southeast’s northern section. Essentially, the project would level the ends of the blocks nearest Kingshighway, the site of the former Central Institute for the Deaf building now used by the St. Louis College of Health Careers, and some land that the Missouri Department of Transportation controls alongside I-64/US-40. Lost would be two single National Register-listed buildings, the Central Institute for the Deaf building (1951-4, William B. Ittner Inc.) and the exotic Lambskin Temple (1927, Nolte & Naumann) and well as 120 dwelling units within the National Register Forest Park Southeast Historic District. The plan replaces Drury Hotels’ invasive 2007 proposal for the same area.

Fortunately, the K2 plan seems to have no political support, but safeguards against its implementation are questionable as well. What real power does Forest Park Southeast have to stop it? Writing about the K2 proposal, NextSTL‘s Alex Ihnen urges neighborhoods to proactively create design visions. Ye the larger failing is not on a local basis. Residents of Forest Park Southeast should be able to look at the zoning ordinances of their city and know the scale and character of permissible development.

Yet Forest Park Southeast residents cannot wait on citywide zoning reform. Fortunately, there is an existing citywide ordinance that allows for progressive design regulations that are enforceable rather than politically malleable: the city’s preservation ordinance. The preservation ordinance allows Board of Aldermen to designate Local Historic Districts that codify design standards governing demolition, rehabilitation and new construction. While these are mechanisms enabled under preservation law, they are the city’s only easily-accessible tool for regulating the form and quality of new construction.

Most of Forest Park Southeast has the historic building density typical of other neighborhoods that have adopted local historic district ordinances. In Forest Park Southeast, most of the neighborhood’s character comes from existing historic architecture, and the smaller number of vacant lots offer opportunities to enhance and extend that character. Local historic district ordinances need not mandate fake-historic architecture. In fact, one of the city’s oldest local historic district is the Central West End, where modern design like the building at 4545 Lindell Boulevard and Lester’s Sports Bar on Maryland has been encouraged by the standards.

The reason that neighborhoods adopt local historic district standards is not to mandate every new house look like a Victorian brick townhouse. The reason is to keep destructive projects like the K2 plan and insensitive new design like the Aventura out. Supporters of local historic district designation mostly want the maintenance of the human scale of building that makes neighborhoods experientially delightful. It’s pretty simple. Humans like beauty, and environments that are safe to walk.

In Soulard there is a great example of the sort of new construction that smart local historic district standards can create. At the southeast corner of allen and 8th streets is a two-story commercial row completed in 2008. While the building is clad in traditional red brick completely on three sides, the detailing is not copying from older styles. Instead, the brick corbelling, stone sills and recessed openings are adapting masonry construction traditions that come from the physical properties of the materials themselves. That is a lot different than the Aventura’s use of brick or siding, which is born out of a compositional confusion rather than material honesty.

The building in Soulard was built to have a pleasant and direct street interface, enlivened through the shadows cast by brick relief. Its material unit — brick — is warm and immediate to the passerby. The building’s proportions and materials harmonize with its neighbors. Still, there is no mistaking the row for a group of historic buildings. Their minimalism, modern windows and use of corrugated metal siding on the rear are very much of the current age. This building reaches back in time not to mimic but to continue design that responds to the psychology of its users. People like beauty, and materials like to be used in certain ways. There are time-honed ways to realize both of these things, and style is only a secondary issue.

A Forest Park Southeast local historic district could be flexible on style and material (brick need not be required), on standards for rehabbing and on building height. Yet the local historic district standards would ensure that the qualities that make the neighborhood a human-scaled place will come from both new and old buildings — each casting value and interest on each other. If Forest Park Southeast is “under siege,” as Ihnen states, there is an existing regulatory method to cast off the invasion of threats to scale and beauty.

7 replies on “Forest Park Southeast and the Human Scale”

That place in Soulard is awesome.

That K2 development looks atrocious. ‘Looks like a CVS, a gas station, and a chain motel. *sigh*

Nice write-up, I’ll only add that in addition to neighborhoods being more proactive in planning as well as stating desired development outcomes, I suggested that existing entities in the neighborhood – the Alderman, WUMCRC, Park Central – must be engaged and should make it clear that the K2 vision will not progress. Short of iron clad prohibition on demolition such as would be required here, the fail safe is political. Existing zoning, national register status, etc. mean that there are many barriers (tools for residents) to a developer enacting such a vision, but we have all witnessed local political leaders and entities find ways to outflank zoning and other seemingly formidable issues.

Has there been any official comment from the organizations or the alderman since your post?

Exactly.

The Aventura is bad enough, but the K2 plan is absolutely one of the most appalling and insane ideas to be proposed by any developer in recent memory. It is especially inappropriate for such a prominent location. A QT, a cheap chain motel, and what appears to be a Walgreens or another CVS in the stead of the Lambskin and several extant homes. How classy of the K2 nitwits to care so much about our City. The funny thing is that this is probably only “Phase 1”. The cookie-cutter sloburban office structures are most likely a “Phase 2”. Which means basically that the land on which they would have been sited will be a vacant and barren moonscape for the next twenty years. Because it is fairly unlikely that any tenants will be found to fill that space, unless it’s possible that they are designed to be offices for medical professionals. And since BJC has its own plans for improvement and expansion (some of which must surely include offices for doctors, etc.) I find any likelihood for medical use highly dubious.

The sad thing is that this is what gets proposed and built in the City these days because the mental midgets in City Hall–including the aldermen and mayor, of course–have allowed this kind of bullshit development for the last twenty years. So why would any developer propose a plan which took into account the existence of human beings? Or the extant design elements present in the surrounding neighborhoods? All of these developments are geared toward one thing, and one thing only: the machine we call the automobile.

Pathetic…and infuriating.

While I agree Forest Park Southeast residents can not wait for city wide zoning reforms. The arguments against K 2 are city wide. It is like the eight elements of a great neighborhood in San Francisco. http://www.sf-planning.org/index.aspx?page=1704 Those principles apply to other city neighborhoods.

In other words residents in Forest Park Southeast have every reason to share their concerns with other neighborhoods in the city, for not only does every project like this have a negative impact on the whole city, it also represents what can, and does happen in other neighborhoods.