by Michael R. Allen

This is the third part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

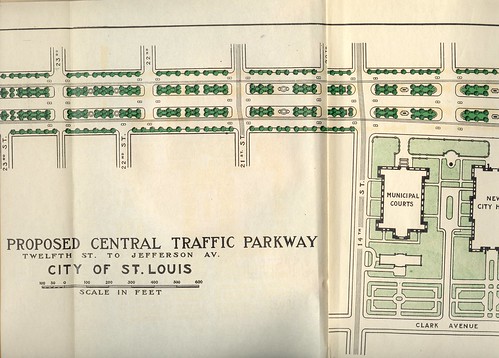

The 1907 Comprehensive Plan’s call for a civic plaza blossomed after the establishment in 1909 of a permanent City Plan Commission. In July 1912, the City Plan Commission recommended to the Board of Alderman a plan called the “Central Traffic-Parkway.” The published report was illustrated with many photographs of “the blighted district” located on Market and Chestnut streets downtown. Described as the initial step in building a greater city, the plan called for the clearance of every block between Market and Chestnut streets from 12th Street west to Jefferson, which would be 26th by number. On these blocks would be built a modern parkway, with divided lanes in each direction and ribbons of green space planted with uniform rows of trees and lawns. The parkway plan called for eventual extension to Grand Avenue. No mention was made of eastward extension.

Although more of a traffic way for automobiles than a true park system, the 1912 design and description were fully rooted in the City Beautiful notion of park function. The theory behind the plan was that the blight of the central city — blight of overcrowded buildings and congested small streets — needed to be supplanted by an orderly place of defined purpose. Here would be a modern space for both vehicular traffic and human recreation. In turn, the parkway would foster stronger property values in adjacent sections and lead to the construction of new tall buildings. This would be the spine of the renewed city, and it would transmit improvement in economy and morality.

The plan is rife with statements hostile to the conditions of the central city, such as this gem: “[e]very public spirited citizen of St. Louis has regretted the depressing influence of surroundings upon the stranger stepping out of Union Station.” Sure, the buildings were old and the restaurants less than five-star but the view from Union Station in 1912 showed a robust city with lots of economic activity. The plan bemoans the lack of park space: “There is not in all this central section a spot out of doors which offers rest.” Never mind that the commercial heart of the city might need to be a bit more restless than other parts, and that there might be people who liked it that way and many more who needed it that way.

The plan stated that there were 101,540 people within easy walking distance of the parkway who would benefit from the recreational opportunities on the parkway. To the north of downtown was the most densely populated part of St. Louis, with a density of 26,218 people per square mile. The city average was 11,193 people. To people living in the crowded central city, “Forest, O’Fallon and Carondelet parks are almost unknown countries” according to the plan.

These premises had a key flaw in that the path of the parkway would eradicate much of the residential population any parkway would have served, through direct demolition and the resulting fraying of community through construction of new buildings. The parkway itself was more of a barrier than a park for human leisure. The narrow park strips served more as medians for the large roadway than as accessible and usable green space. Besides, people living in the central city were dependent on the availability of goods, services and employment within a few blocks of home. They were unlikely to travel a dozen blocks to walk down a parkway.

After the city passed a new charter in 1914, the City Plan Commission endeavored to persuade voters to approve a referendum for the central traffic parkway. Predictably, the referendum had the strong support of business leaders, Mayor Henry Kiel, downtown property owners eager for higher land values, and Central west end residents anticipating an easy commute out of downtown and the dirty central city. Less predictable was the larger coalition of opponents. North and south side residents saw dubious value in the central parkway, while the largely poor and African-American residents of downtown and Mill Creek Valley saw the parkway as the elite’s means of eradicating their enclave. Few saw the linear parkway as true recreational space, or even as the civic center the city lacked. Instead, it seemed more like a roadway designed for the private benefit of adjacent property owners and West End residents. The rational planning agenda could not overcome deep opposition, and the referendum failed on the June 1915 ballot.

That might have been the end of the notion had it not been for Harland Bartholomew. In 1916, the City Plan Commission hired the young planner as its first staffer with the title of Engineer. Bartholomew was a dedicated proponent of City Beautiful. He considered central St. Louis congested, confusing, and lacking any grand open spaces. Bartholomew pointed out that a pedestrian could not approach City Hall but merely pass by the building. To this planner, the density around City Hall was not a hallmark of a metropolitan city but rather a symptom of a lack of the grandeur important cities should have. He aimed to revive the general idea of the civic plaza outlined in the 1907 Comprehensive Plan. Instead of a large roadway, he proposed the Public Buildings Plan with park space on existing blocks in the area immediately around City Hall and the new Central Library.

4 replies on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 3): The Central Traffic Parkway Plan of 1912”

Excellent and interesting posts, the nearsighted efforts continue to today. I will be surprised of the current 4.7 million dollar sustainable planning grant given to the region will produce anything usable. Some of the mistakes will take decades to correct, phasing out the wrong buildings, the wrong public spaces in the wrong places and so on. It is a complex discussion, but can be simplified to density, transit, walkability, and the formation of public space. I especially point to the 1956 St. Louis City Land Use Plan and pages 8 and 9. Page 8 showing existing commerce and Page 9 showing proposed commerce. It is the root of the problem that encompasses all of the above points of density, transit etc.

They have largely succeeded in creating the elitist goals of page 9, commerce controlled by a few insiders, commerce dependent upon the automobile, and what follows is the destruction of the city, transit and the urban environment.

It is an extension of the failed mall plans, which even today are ineffective for myriad reasons.

Of course all of the yes men and women, the insiders who agree with the agenda, who have been designated to manage the sustainable planning grant. The poorly conceived Gateway Mall is not likely to go away anytime soon.

I would also point to Ron Fagerstroms book, “Mill Creek Valley, A Soul of St. Louis” as another reference documenting the changes in this corridor and how they happened. (Used to be at Subterranean Books in U City and from the author in Lafayette Square, I think it is still available).

In any case Michael, nice posts, in depth and thought provoking.

There is something notably fascist about this imposed simplicity – the attempt to force a perhaps “scientific” order upon the supposed chaos of a naturally-evolving city.

All to often I find myself saying, ‘I wish stl was like this.’ It’s sad to think that it actually was…

It really is sad. While Burnham was designing a city in Chicago, we were playing whack-a-mole with minorities.