by Michael R. Allen

This is the seventh part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

At the end of the 1970s, after failing to build the winning design from the 1967 design competition, city leaders did not let the dream of a “completed” Gateway Mall die. There still were blocks of old buildings to clear and new corporate high-rises to attract. However, developer Donn Lipton seized the opportunity of city inaction and in February 1977 submitted a redevelopment plan for the blocks between Seventh and Tenth streets radically different than the Sasaki plan.

Lipton and architect Richard Claybour created a plan for attracting more development and creating park space, using the existing conditions of those blocks. The alleys of each block would become lively enclosed parks, surrounded by rehabilitated historic office buildings and a few new buildings. One could still have stood on the steps of the Civil Courts Building and have gotten an axial view to the Arch, but in the foreground would have been several blocks of integrated green space and vital activities. Here was the chance to take the reasonable idea that downtown needed better green space without using it to tamper with the urban qualities that made downtown what it was. On top of it all, immediate economic development would accompany the introduction of green space. Downtown business leaders submitted their own plan that month to raise $6 million in bonds to complete the mall. Proponents claimed that downtown would stagnate without the completion of the Gateway Mall east of Tucker.

Mayor James Conway appointed a task force including Lipton and downtown businesses men to study how best to proceed on the Gateway Mall. The task force hired Sasaski, Dawson & DeMay to complete a report that was completed in September 1978. Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay’s report threw a spanner in the works of the firm’s own earlier master plan by recommending Lipton’s plan as the most economically sensible plan for downtown. Downtown businessmen went on the offensive, however, and persuaded Mayor Conway to throw the task force report away and hire Sasaski again with the order to come up with a workable plan for an “active linear mall” between Seventh and Eleventh streets.

Sasaski’s new vision retained little from the 1967 proposal, instead relying on activating uses like a greenhouse between Broadway and Sixth, an aquarium between Seventh and Eighth and a museum between Eighth and Ninth. The one nod to Lipton was retention of the Western Union Building at the southwest corner of Ninth and Chestnut Streets. However, this preservation plan was based on the expense of relocating the telegram cables rather than interest in retaining any existing buildings. Downtown business leaders next commissioned HOK to plan the specifics of an $89 million Gateway Mall completion.

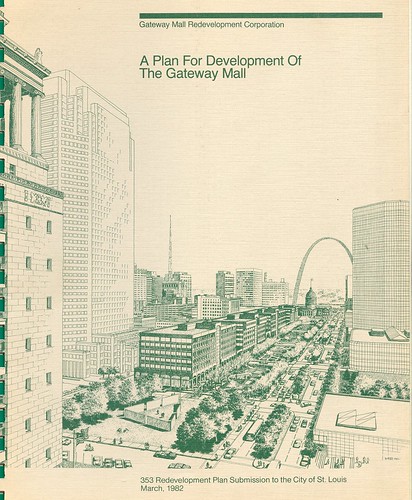

Alderman Bruce Sommer (D-6th), who represented downtown, opposed the new Sasaki plan and came out in support of Donn Lipton’s plan. In 1981, Lipton picked up more support when Vincent Schoemehl, Jr. was elected mayor. Schoemehl favored the Lipton plan, and his first action was to legally blight the blocks between Seventh to Tenth streets to open them to a formal Request for Proposals. Four plans submitted by the April 1982 deadline included one by Lipton similar to his 1977 plan and one by the new Gateway Mall Redevelopment Corporation that introduced the “half mall” concept.

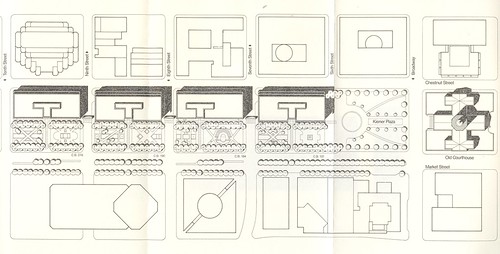

Downtown business leaders led by KMOX Chairman Robert Hyland formed the board of the new corporation and explained the abrupt change of plans: They had considered the options, and with declining city revenues had decided that creating park space alone was financially impossible. What was needed to make park space possible was income-generating activity. Instead of whole park blocks, the corporation wanted to build “half-mall†blocks that situated five-story office buildings on their northern ends and park space on the southern end and middle. The buildings would subsidize the park space and create thousands of square feet of desirable Class A office space. Restaurants and shops on the ground floor would direct pedestrians out onto the park blocks where they could frolic and reflect in a rigidly-designed landscape.

The Redevelopment Corporation made no bones about its chief purpose: “attracting more development.” Critics quickly pointed out that the blocks in question were already developed with buildings on their northern – and southern — halves. Why bother?

The result was predictable: civic leaders derided the Lipton plan as last-minute (even though it had actually been first in this recent round of planning debate) and insufficiently grand. They stood by the rationalist urban planning vision of order through total replacement, but with an almost absurd new twist of replacing urban building stock with new building stock to “complete” a linear open mall. After intense lobbying by labor interests caused Mayor Schoemehl to reverse his position, Schoemehl helped put together the new Pride Redevelopment Corporation. In October 1982, the Board of Aldermen approved a redevelopment agreement with Pride Redevelopment Corporation by a vote of 26-2.

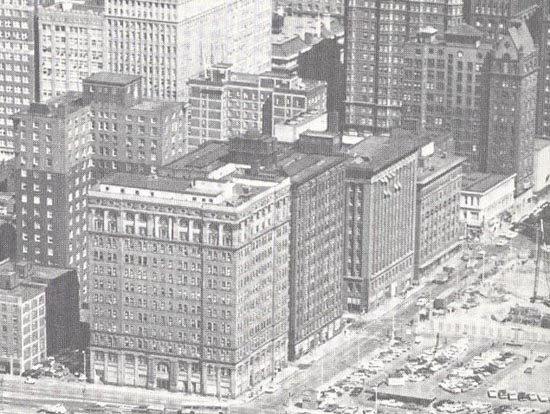

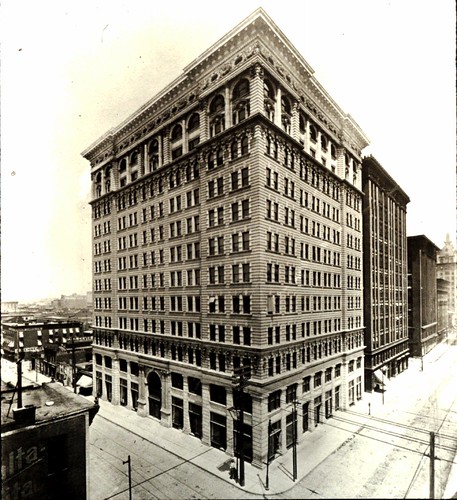

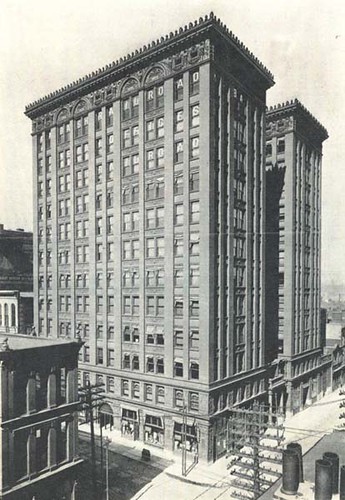

An arduous two-year battle followed to preserve the buildings in the mall’s path. Three large historic office buildings, the Title Guaranty, Buder and International buildings, were demolished by the end of 1984. (Landmarks Association of St. Louis had moved its office to the Title Guaranty Building to show its conviction in preservation of the buildings, was forced to relocate ahead of the wrecking ball.) Destruction of several smaller historic buildings, known as Real Estate Row, took place in the next two years. All of these buildings were deemed eligible for the National Register of Historic Places by the National Park Service. They provided visual context for the landmark Wainwright Building, although Mall proponents somehow declared the loss of context an improvement. However, preservationists created Market Preservation, Inc., a new advocacy organization that fought to save the buildings. Market Preservation lost the battle but waged the strongest preservation effort in the city’s history, and for good reason. The demolition of historic buildings for the mediocre Gateway One building and its anemic plaza inverted the whole purpose of parks: to provide public beauty. The public beauty of great architecture was destroyed to create a privately-controlled visual offense.

The half-mall block quickly garnered infamy. The office building built on the northern side of the block, Gateway One on the Mall (designed by Robert L. Boland, Inc.), was an uninspired mass that ended up being 15 stories and dwarfing the Wainwright Building. The park on the southern end was marked with plinths advertising the office building at Market Street, making it seem like an extension of the building’s private world. The block seemed like an intrusion into the Gateway Mall, not its logical completion.

Plans fizzled for developing the next block west in the same manner, although that block was cleared for use as surface parking lot. Kiener Plaza was extended west, with 6th Street closed, in 1986 to include postmodern Roman ruins with a cascade called the Morton D. May Amphitheater (designed by Team Four). How this related to the earlier statue of the runner in the circular fountain remains anyone’s guess.

Ending where he started with downtown planning, Mayor Schoemehl announced plans in 1992 to finally “complete” the Mall before he left office. He intended for the city to acquire the two blocks between 8th and 10th streets and to demolish remaining buildings, including the landmark Western Union Building. In 1994, the landscaped blocks opened and only added to the visual confusion.

With empty center lawns and flanking rows of trees (asymmetrical here), the plan seemed a rehash of the Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay plan. Upon seeing the plans, architect Gene Mackey called the mall a “series of unconnected, unrelated blocks.” So it was. A brief bright spot occurred in the winters of 1999 and 2000, when the city opened a highly popular temporary ice skating rink on the block east of the Serra sculpture.

7 replies on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 7): “Pride” and the Mall”

I really don’t understand the point of the gateway mall, besides knocking down old buildings. Why would you put a freaking park in the middle of the city? Really? Am I missing something here?

I think that green space in a Central Business District is just fine, when done well. Â The problem it, this wasn’t done well. Â It’s only been in recent years, with the addition of Citygarden, that we’ve finally started to see the mall even begin to reach its potential. Â The important thing to consider in current context is that downtown is now a thriving residential neighborhood in addition to the CBD.

Wow, this is amazingly depressing.

Attract jobs and suburbanites. That’s it.Â

Yeah, but as Michael pointed out Citygarden was some fine buildings. They were small, would have commanded low rents. Cities are about people and people like cheap rents in historic buildings. We have enough parks and green space. The Gateway Mall is a failure and will continue to be until its abandoned. Too bad we don’t have enough demand for new construction to abandon it. In this respect we are path dependent. The institutions that decide this was a good idea are still around and we don’t have the capacity to do otherwise.Â

Shit, your breaking my heart all over again. I lived through the debacle that was the Scheomehl admins Mall Plan. Seeing those beautiful buildings (which were at least partially occupied before the whole mess began) brought down for something so tawdry and utterly lacking in aesthetic appeal as what currently sits there was gut-wrenching. The whole Mall idea should have been aborted from the get go, but unfortunately there are always ignorant pols and the stoopid wealthy (whose taste is all in their mouths) running around like gadflies making a fuss over their pet projects. A horrible, shameful enterprise that never should have come to fruition.

It’s like getting kicked in the nuts…

So sad to see them go. Â What a shame. Â Those buildings would be so desired today. Â How do people who don’t see the value get into positions of power?