by Michael R. Allen

[Previous coverage: The Precarious Condition of Two Beautiful Houses on St. Louis Avenue, August 12, 2009]

The front elevation of the Bernhardt Winkelman House at 1936 St. Louis Avenue has become a quiet cultural icon for visitors to the near north side. No other front wall in that area may be as much-photographed, with a possible representational life without end. There is no doubt that the diminishing state of the built environment has enhanced the visibility of the three-story stone-faced house, but there also is a certain decorative quality possessed by the front elevation that is notable in its own right. To state that the façade is beloved would be an understatement, but also an assertion closer to the fact of the building’s status than any more formal descriptors. The Winkelman House, imperiled though it may be by current circumstance, may well be the popular emblem of the St. Louis Place neighborhood’s store of high-style residences.

Officially, the Winkelman House is a contributing resource in the Clemens House-Columbia Brewery Historic District (NR 7/22/1986). Built by German-born wholesale grocery merchant Bernhardt Winkelman c. 1873, the house contributes to two areas of significance identified in the 1986 amendment to the District nomination: Architecture and Ethnic Heritage. In 2009, owner Northside Regeneration LLC (which purchased the house in 2005) placed the property on its list of “Legacy Properties” identified for preservation — a list required as part of the city’s master redevelopment agreement with Northside Regeneration.

Today, after being severely damaged by brick thieves, the house stands in grave danger of being lost despite the fully intact primary elevation. Northside Regeneration now is exploring preservation of the remaining part of the house, including submission of an application for federal and state historic tax credits for the remaining portion. Whether the remains constitute a “building” eligible for those credits is less than a certainty, making the fate of the Winkelman House’s front an urgent preservation question. Although the façade’s preservation may now seem an artifact, and its restoration an act of architectural historical veneration, actually the façade still forms part of a cultural context.

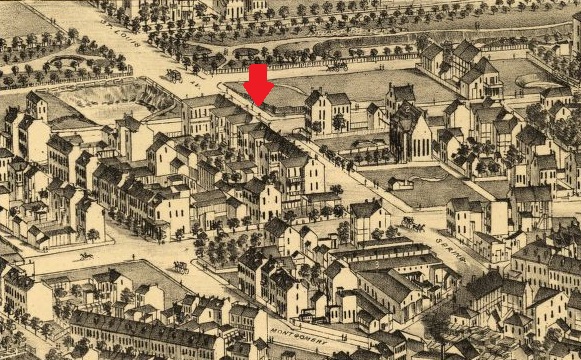

Bernhardt Winkelman was one of a number of prominent German-born businessmen who settled on St. Louis and Rauschenbach avenues around St. Louis Place Park. Many of these men came to St. Louis after the failed 1848 revolution, bringing democratic ideals and later playing a major role in the cause of abolition during the Civil War era. St. Louis Place had been platted by investors in 1850 ahead of annexation into the city in 1855. Originally the north-south park mall was intended as a private place, free from vehicular traffic, much like Regent’s Park in England (1811-25; John Nash, designer) and subsequent English and American “park†developments. However, investors deeded the park to the city of St. Louis, and streets were added on each side after 1865 to “[define] its character as a public park more clearly” according to Parks Commissioner Theodore Link in an 1877 report.

Consequently, the larger residences intended by the original plat ended up being built on St. Louis Avenue, which was somewhat removed from the public activity in the park. Some large residences were also built on the west side of Rauschenbach Avenue north of St. Louis Avenue from 1870 through 1912. Many residents along St. Louis and Rauschenbach avenues were leading members of North St. Louis’ business and professional communities, self-made German businessmen, industrialists, and professionals who built homes comparable in cost and style to those in more exclusive districts in South St. Louis and the West End. Most of the houses still stand, providing a physical richness to the story.

The Clemens House-Columbia Brewery Historic District amendment documentation, written by architectural historian and current Missouri Advisory Council on Historic Preservation Chairperson Mimi Stiritz, identifies the Winkelman House as one of only two stone-faced houses within the District and as a “particularly fine example” of a stone façade from the 1870s and notes the presence of Italianate, Second Empire and High Victorian Gothic elements. The sandstone facade is by far one of the most significant on St. Louis Avenue, and among the best examples of such a front in the city. Typical townhouse elevations in the Italianate and Second Empire styles consist of simple, straight stone fronts, wooden or sheet metal bracketed cornices, and high mansard or low hipped roofs. This house has a more complex form and Gothic arch forms elements popularized by then-contemporary work by Philadelphia’s Frank Furness and other architects.

The stone of the front elevation appears to be Warrensburg blue-gray sandstone obtained from either the Pickel or Bruce quarries which both opened near Warrensburg, Missouri in 1867. The excellent condition of the stone suggests that it came from deep in the quarry where the finest grained stone was located. The stone was cut by the Pickel Cut Stone Company of St. Louis, and exhibits a level of relief and quality rare among remaining examples of Warrensburg sandstone-faced buildings. Warrensburg stone was used widely throughout the region, including on the Arkansas State Capitol. Houses around St. Louis Place Park generally used native limestone, including stone quarries by the Sheehan brothers on the south side of the 2200 block of St. Louis Avenue until the late 1880s. However many homes in the neighborhood made use of the soft blue-gray sandstone, including an Italianate residence at 1927 St. Louis Avenue (1879) that the city demolished in 2011.

By the early twentieth century, the St. Louis Place enclave was losing its fashionable status, and many residents moved to the Central West End and West End or to new north side subdvisions like Plymouth Park near O’Fallon Park (platted in 1906). Winkelman passed away during this transition. According to a 1913 St. Louis Post-Dispatch article published upon his death, Winkelman was a “wealthy grocer” with a substantial estate including the house on St. Louis Avenue and two other homes in a “Winkelman Place” (no street by that name exists). Possibly these residences were adjacent to the house.

The Beiderweiden Funeral Home purchased the residence from the estate and added one-story flat-roofed brick additions at the rear and on the west side. The western addition, with a fairly unremarkable front elevation, houses the funeral chapel, and is now completely destroyed. The property became the Beiderweiden North Chapel (the south chapel was located at Chippewa and Grand avenues). Use of former mansions as funeral homes after wealthy neighborhoods’ property values started depreciation was common in St. Louis. In St. Louis Place, another elaborate high-style stone-faced residence at 2223 St. Louis Avenue dating to 1887 became the Leidner Funeral Chapel in 1921, and was also expanded with a chapel wing (this one, however, was a refined Gothic Revival addition built by Charles P. Reichers).

The Winkelman House was in use for funeral services until 2005, when Northside Regeneration’s predecessor holding company Blairmont Associates LC acquired the property. As mentioned, when Northside Regeneration obtained public redevelopment rights to a 1500-acre area of north city that included the Winkelman House it filed a document stating that it planned to preserve the Winkelman House. While that promise has been on the table, illegal demolition destabilized the building to the point where the company obtained a demolition permit this summer. However Northside Regeneration has halted demolition to explore preservation.

Whether the façade is retained on site or salvaged and relocated, the Winkelman House is no longer what it was when a wealthy businessman built it. Today St. Louis Place has no elite grouped in mansions around a green lawn, and it lacks the building density that made the differences between the mansion-dwellers and the working-class residents around them so stark. The Winkelman House no longer reads as a mansion, but as a fragment of a changed and regenerating neighborhood (“regeneration” fits nicely with the developer’s own goals and rhetoric, too). Its preservation would definitely forge a “new kind of relationship to the people whose history is being represented,” to quote Dolores Hayden in The Power of Place. That relationship would render the sandstone façade a landmark of popular appreciation, freely visible to future generations as the gift of ours.

3 replies on “The Winkelman House on St. Louis Avenue: A Popular Emblem, Fading Away”

It’s sad isn’t it?. Paul McKee is dishonest as hell. Sometimes it is hard to read your posts.

One thing is clear, Paul McKee is a disaster for the Northside, he’s not going to regenerate anything except steal what he can of public monies so he can regenerate his pocketbook. It’s absurd the State of Missouri is giving him hundreds of thousands of dollars and he can’t do any more than let significant buildings crumble. (What does this mean for the more common buildings that make up the fabric of these neighborhoods?)

And where the hell is the city in all of this? This guy should be fined daily. In Lafayette Square if one paint chip is out of place they treat you like a felon.

This building is pitiful display of government failure if there ever was one.

Thanks for the research though, an interesting background to the building. It will be a miracle if it is saved though,

As I was researching the property, and found this blog post, I was actually surprised to find it is still partial standing. I’ll have to go back and capture what’s left.

Here is another photograph of the ‘Winkelman House’ linked to my Flickr below, taken in January, 2012. A trail of bricks caught my eye perhaps four blocks south and led me to Saint Louis Ave. At that point nobody had bothered to gather the bricks scattered across the lot and alley.

Thanks for the post!

http://www.flickr.com/photos/michaelbrennan/8239981836/in/photostream

Cheers,

Another Michael

From Paul McKee’s open letter last year: “McEagle made a commitment to the people of the Northside and to the historic preservationists that we will renovate, and reuse the historic and reinvent salvageable structures in the Northside area. We will stand tall and meet our commitments even when unforeseen problems occur.” Let’s see his company abide by this promise.