by Emily Kozlowski

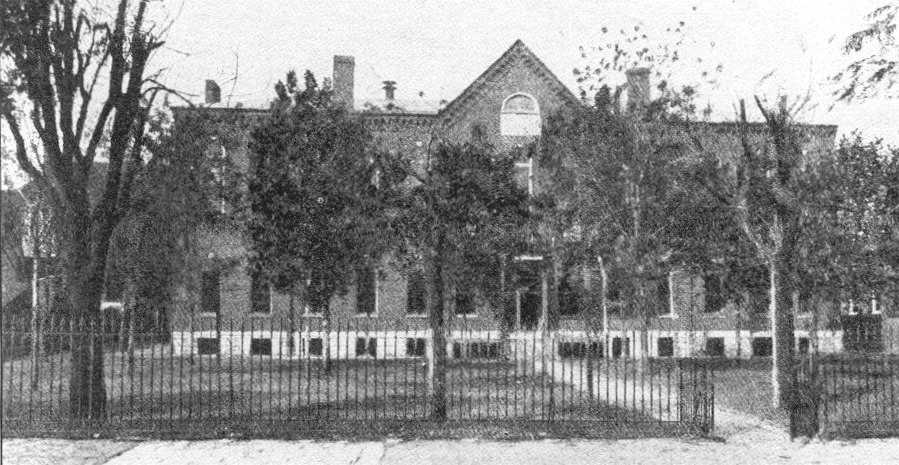

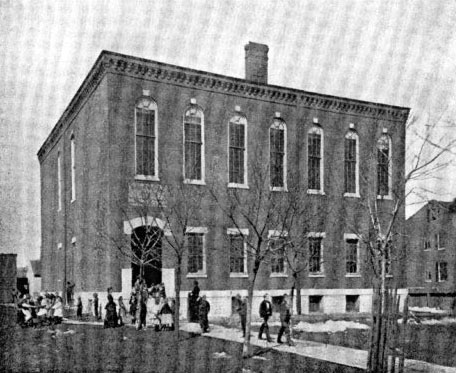

A quick pass down North 20th Street gives a glimpse of an unassuming brick school house, surrounded by a concrete lot and a chain-link fence. In front of the building is a small market and behind it is a residential street. Upon closer inspection, you begin to notice more. It is made of a deep red brick, thirteen bays wide, two stories tall, with a limestone clad foundation and a porch dressed in cast-iron.

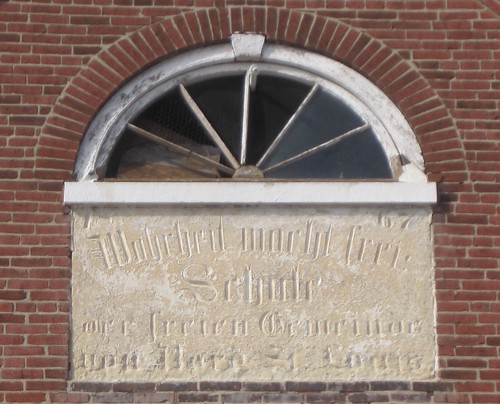

Most recently used by the Youth and Family Center, but abandoned since 2009, the building has since not received much attention. This is obvious, as water damage has accumulated and now whole sections of walls are quickly crumbling. In a matter of weeks, the building’s stability drastically worsened and in late February the roof over the gymnasium collapsed, pulling down much of the second floor. As bad it the building looks, its history that would surprise most, with connections that reach farther than St. Louis. An inscription on a limestone block above the main entrance reads “Warheit Macht Frei: Schule aud Die Freien Congregation von Nord St. Louis” or “Truth Makes One Free: School of the Free Thinkers of North St. Louis.” The building, dating back to 1867 and expanded greatly in 1883, once housed the German-American group, Die Freie Gemeinde.

In 2011, Preservation Research Office completed the National Register of Historic Places listing for the St. Louis Place Historic District. Working under the direction of then-Alderwoman April Ford-Griffin, we made special effort to extend the eastern boundary of the district to encompass this building. This effort allowed the building to be eligible for historic rehabilitation tax credits, and everyone was hopeful that it would be a prime candidate for rehabilitation.

Beginning in 1848, German intellectuals began fleeing their country after a series of failed political and economic revolutions. The United States saw a sharp influx of immigration as a result, with a large German community settling in St. Louis. (Think Dutchtown, Hyde Park, Anheuser-Busch, etc.) The Midwest in particular became a home to the Freie Gemeinde, a school of German thought with foundations in the Catholic and Protestant churches, from which it ultimately separated. Their main purpose was “to unite the foes of clericalism, official dishonesty and hypocrisy, and to unite the friends of truth, uprightness, and honesty.” It was a philosophy that embraced the individual instead of institution.

The Freie Gemeinde, which translates to “the free congregation,” believed that man has the basic right of applying knowledge of history and science to religion, choosing which aspects of faith are reasonable and which should be disregarded. The church fought against this individualized idea of religion, instead defining faith as an acceptance of dogma without question. The Freie Gemeinde also applied individuality to religious institution. They removed the hierarchal structure of the church, allowing for each congregation of Free Thought to exist on its own without a superior body. Churches came to be referred to as halls and a pastor or priest became a “speaker.” In a Freie Gemeinde Hall, the congregation attended lectures on subjects ranging from science to philosophy instead of the traditional sermon, even encouraging discussion during lectures. The group was ahead of their time and influential as immigrants in the Midwest. Today, the last remaining Freie Gemeinde exists in Sauk City, Wisconsin.

The building at 2930 N. 21st Street was, at one time, referred to with a full German name – Freie Gemeinde von Nord St. Louis und Bremen. The first Freie Gemeinde group in the United States formed in St. Louis in 1850, a leading example to other congregations that sprang up across the country. This was the first community center in the neighborhood and boasted a library of over 3,000 books in German. It was a large meeting hall for discussions and education in philosophy, literature, science, and other topics.

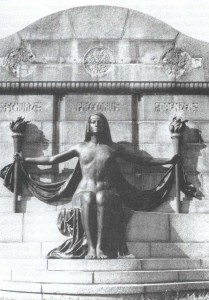

Three men associated with the Freie Gemeinde von Nord St. Louis, Preetorious, Danzer, and Schurtz are famous for their association with local German newspapers. As editors of the Westliche Post and the Anzeiger des Westens, they openly criticized religious oppression and slavery. The Naked Truth Monument in Compton Reservoir Park is dedicated to these three free thinking Germans. The bronze woman symbolizes truth, holding torches of enlightenment for both Germany and America. The inscription, in both English and German, tells of the German-Americans dedication to their adopted country. Just north, nestled between a market and a row of houses, the building where these men and many other German-Americans met and formed a community is crumbling and slipping away from public memory. Little does St. Louis know, the real monument is falling.

6 replies on “Old Free Thinkers’ School Falling in St. Louis Place”

It’s such a shame to see this legacy crumbling. I’m involved with the Ethical Society, which carries forth a related branch of thought in St. Louis, but I wish these old institutions could survive.

Do you think brick thieves are at play here?

Even with the damage in the rear in 2012 it sure seems to me it is being helped along given the appearance in 2009. Who owns it? I can’t recall the building off the top of my head. It reminds me of what happen to the Turnerverein in Hyde Park. But it took years and serious deterioration for that building to begin similar collapse as you are showing. I’m not saying it is not possible, but it looks suspect to me.

Isn’t this part of Paul McKee envelope? Actually isn’t St. Louis Place also part of that envelope?

Sad. It is also a matter of historical record that these newly American men and women played a huge part in keeping Missouri out of the CSA, during the Civil War. And to a very large extent, the grandchildren and great-grandchildren of these patriots have fled the City their ancestors so valiantly defended from tyranny and institutional ignorance. Interestingly enough, the Turnverein movement was also started somewhat before the Frei Gemeinde, and its founder, Friederich Jahn, who at one time was seen as a stout German patriot, was also the subject of political persecution during the turbulent (18)’40’s in Prussia and the allied German states. As well, and not so coincidentally, the theories of Karl Marx and Friederich Engels on political and economic functions in society were also ascendent during this time.

A tragic end for a handsome and historical building. Truly angers me that some rich f*** will probably end up with the plaque.

Ps: there is a monument to Friederich Jahn in Forest Park, just over the hill, to the N-NE of Shakespeare’s Glen, near the Art Museum. Wouldn’t it be nice if it were restored, and perhaps moved to a more prominent spot?

I’m pleased to see this article, sad as the occasion is. Through the initiative and leadership of the Preservation Research Center and the cooperation of the building owners (the Youth and Family Center), I have confidence that if the building itself cannot be saved and restored, at least its valuable artifacts will find a good public home in St. Louis. And if, for some reason, that can’t happen, there is a pretty good alternative — certainly better than the dark-side option mentioned by samizdat.

I am a member of the only surviving Freie Gemeinde (in Sauk City, Wisconsin) of the 200 or so that were established in the U.S. in the second half of the 19th century — of which, as the article notes, the St. Louis congregation was the first. Our small town location certainly helped us make it through the two World Wars with Germany, when anti-German sentiment was institutionalized (and made public policy) in many of this country’s large cities. (We have also adapted and made some strategic – if painful – compromises along the way, such as affiliating with the American Unitarian Association in 1955 to build membership and ward off the feds and the IRS, who, in the reactionary 1950s, didn’t need a whole lot of excuse to bar the Congregation’s doors — and go knocking on individual freethinkers’ doors — in the middle of the night.) We enjoy a historic (and National Register) building, Park Hall, built in 1884 by Wisconsin’s second most famous architect, Alfred Clas. (More at http://www.freecongregation.org) Like the Freie Gemeinde von Nord St. Louis, we have a sizeable library and archives; theirs are in the good hands, but deep caverns, of the State Historical Society; ours, for the most part, are on site. But enough of that: we aren’t greedy to have what truly belongs to St. Louis.

A question concerning the captions to the photos in the article: under the close-up of the inscribed stone, the caption says that it was “added in the 1883 expansion of the building.” But a very similar stone appears above the entrance in the photo of the “earliest northern section in 1867.” Might these two stones be one in the same? And is it possible that the original (1851) Freie Gemeinde von Nord St. Louis building, on 14th and Hebert Streets, had this same stone?

Howsoever the fate of the 20th Street building is decided, we in Sauk City stand in solidarity with those people and organizations of St. Louis who are making every effort to preserve and/or recognize this historic landmark.

It is sad that st louis has lost the somewhat spontaneous

intelletual activites fostered bythe German immigrants in the

19th century. We do have our univerities, which perhaps

collectively exceed the amateur status of the old days, but

the 19th century movement seemed much more interesting.

And the contrast between what the German immigrants did

compared to the Germans who stayed in Europe in the 20th

century is nothing short of amazing.