by Michael R. Allen

Now that I live south of Tower Grove Park and work at Cherokee and Jefferson, my daily path has taken me through Benton Park West’s grid of state streets. Some blocks and buildings are familiar from my previous years living in Tower Grove East, but others are new. The dense cavalcade of vernacular red-brick (and some frame) buildings seems unending, and any way to and from the office seems to be the perfect way.

Still, as an architectural historian who works in historic preservation, my eye tends to wander toward the broken, the changing and the potential-filled buildings. The streets around Cherokee Street are changing a lot, but not always in concert with the renewal that is changing Cherokee almost-universally for the better. As with the relationship between Manchester Avenue and the rest of Forest Park Southeast, the relationship between Cherokee Street and its surrounding neighborhoods evokes a sense of social and architectural division. Then, of course, within the streets around Cherokee blocks are different from each other in unforeseen ways.

This week a journey down Utah Street brought me into contact with two blocks in the midst of changes wrought by abandonment. The first of these is the 2700 block, between Iowa and California. On the south side of this block is a row of six houses marred by a vacant lot. Flat-roofed, with overhanging hoods and other elements, the brick houses are typical early twentieth century dwellings for this part of the city. Some people know these houses due to an unfortunate abnormality: several of these are crooked, sinking lop-sided below their lawns. The vacant lot marks the site of the first demolition, necessitated by a severe structural failure caused by subsidence. This demolition very likely won’t be the last.

Although these houses are contributing resources to the Gravois-Jefferson Historic Streetcar Suburb District, their preservation is doubtful. Currently, the house at 2746 stands boarded following a fire. Two doors over, the house at 2750 is boarded up and sports a sign placed on it by the city’s Building Division notifying people that it has been condemned for occupancy.

The vacant lot is owned by the city’s Land Reutilization Authority, but the other houses have private owners. The owners seem powerless to fight the tendentious pull of gravity on the building’s walls and porches. The slanted floors seem to be so bad that occupancy of the leaning houses is unfathomable, yet the flats inside continue to cycle tenants — until, I suspect, the conditions are so severe that condemnation occurs.

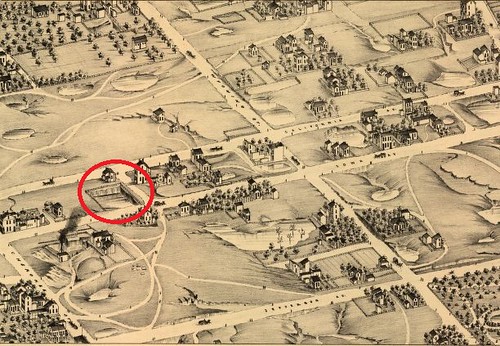

The subsidence of the houses on the 2700 block of Utah Street is not an accident. Much of the surrounding part of south St. Louis historically has been marked by Karst topography that included massive sinkholes, some of which drained into the area’s underground caves. Yet the 2700 block of Utah’s problem is man-made. The plate from Compton and Dry’s Pictorial St. Louis atlas of 1876 shows that the site of the houses was at the time a stone quarry, dug out deep. The western end of the block seems to be unexcavated, and today the two-story commercial building on that site does not sag like its neighbors. To the southeast, the plate shows an active quarrying operation.

The 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map, seen here, shows that the row of seven newly-built houses were alone on the south side of the block. These houses had been built atop the quarry site. Whatever method was used for fill was inadequate, and today the houses’ foundation walls — built of the same limestone that would have been extracted from the site — are descending toward the center of the earth. Any future development of the block will need to address the soil condition.

Four blocks to the west, I noticed another vacant building within a larger building group. At the southeast corner of Michigan and Utah is a group of four two-family buildings that step up along a street slope that rises toward the river. Built in 1905 by contractor Joseph D. Hesse, these red brick buildings are among the city’s short list of dwellings within attached rows. Each building sits on the sidewalk line, and is divided into two dwelling units. Such built density is rare in city neighborhoods, especially west of Jefferson Avenue.

The buildings have very plain flat-roofed forms. Yet their front elevations rise into stoic, low-relief corbelling that is further proof of the endless geometric possibilities of red brick masonry. Wooden hoods with sprung brackets likely came after construction and added a Craftsman element. Beyond a catalog of architectural characteristics, these buildings are unusual, well-detailed and excellently-sited.

Over the years, each of the four buildings has ended up in different ownership. Alterations and upkeep vary, and the easternmost of these is now vacant and boarded. Geo St. Louis shows that the vacant building is owned by Gerald Cain of Jersey City, New Jersey. The distance from New Jersey to Utah (Street) is pretty vast, but hopefully not so far that the owner is unaware of this building’s condition.

Other blocks of Utah Street between Jefferson and Gravois offer more eclectic residential building groups, churches, single-entrance apartment buildings and corner storefronts. In fact, the relatively great number of corner storefronts is notable given that streetcar lines ran down Cherokee and Wyoming, not Utah, in the era of the streetcar. Yet Utah in Benton Park West would have been one block away from two different lines, making it a well-served street with a lot of pedestrian cross-traffic.

Today Utah Street retains the architectural character that all of this past activity helped shape. Abandonment disrupts the built environment as once did quarry-sites and unfinished streets, creating spatial and psychological differences between sites within the same small landscape. In The Arcades Project, Walter Benjamin reminds us that: “As theshold, the boundary stretches across streets; a new precinct begins like a step into the void …” Voids in the supposedly-continuous historic city evoke boundaries — between buildings on blocks of Utah Street, between blocks of Utah Street, between Utah and Cherokee streets, between Benton Park West and the rest of the city. Yet urban boundaries are always cast within a living whole. The impact of sinking houses or out-of-town owners’ landlording ripples through an entire network of relationships and perceptions to affect an entire city.

3 replies on “Two Blocks of Utah Street”

A quarry…I always wondered why so many of the buildings at that end of the street were leaning. Always loved that row of descending attached two-families, too.

I remember in the seventies when I rented “the leaner” along Missouri Ave across from Lafayette Park. It is gone now. I found out later from Compton and Dry it was sitting on an old sinkhole. Stabilizing these buildings on Utah is not impossible, but no doubt difficult.

The big worry is the encroaching demolition on the South side. The Utah row may have valid reasons for coming down, but I don’t think that can be said of other recent demos on the South Side (I am thinking of a sound commercial building on Cherokee and a residence on McKean not even a block from Grand Ave.

Both buildings were easy to save compared to this row on Utah. The process is so screwed up, these demo’s fly beneath the radar. I went through the building on Cherokee, it was fine, it needed rehab, but is was sound. It was a 3 story mansard with a newer replacement brick facade, easily fixed, even if not right away. The building on McKean was a two family, two story with a tree growing up and damaging the brickwork on the rear. It was basically minor damage, although it looked bad.

An overall process has to be put in place that at least protects the southside from the same predatory demolition that has made the northside a wasteland.

The demolition process is random and out of control. It should be part of overall city planning effort.

Particularly the demolition of the sound commercial corner building on Cherokee (and I think Nebraska) demonstrates the pure folly of government. They have issued numerous building permits just a few blocks away. it is clear Cherokee is reviving up and down its length.

Yet a sound building comes down. By making the demolition process so dependent upon aldermen you get fractured results like this demolition.

Until the overall demolition strategy is known city wide, it is impossible to know the direction of the city. If the city cannot even commit to saving easy, economically viable buildings like on Cherokee and McKean (across from Pius), how is it possible to expect them to even remotely care about the buildings on Utah?

Brother, ain’t that the truth. I live on Louisiana Ave. in Dutchtown, and two buildings, one a two-family flat on Louisiana, second (from S to N) in a row of four identical homes, the other a single family not 150 ft. around the corner from it on Meramec, were razed a few months ago. Both in good condition, with a fairly minor front parapet collapse on the Louisiana address, and missing window sashes and casings on the front elevation of the Meramec address. Both of these conditions were not a threat to the structure of either building, though it is likely that without some remediation in the future, the Louisiana address could have developed some structural problems. However, at the time they were pulled down, there appeared to be no outstanding issues with regard to the integrity of structure. It’s almost as if they were disappeared simply because they looked unattractive to anyone passing on Meramec. Since they were in the Gravois-Jefferson Streetcar Suburb N.H.D, and subject to conservation review, it’s a mystery to me how they managed to sneak in under these rules. Unless of course, someone with connections had a hand their demise. It’s a little distressing to see the same disease which started on the North Side spreading to the South Side. With scarcely a peep out of anyone.

The idealist in me wants to believe that this will change. But the cynic in me sees the problem getting worse.