by Michael R. Allen

On October 17, Grand Center, Inc. applied for a demolition permit for the curious hybrid building at 3808 Olive Street. Today, crews were “doing taps” — removing the connections between the building and the city’s water and gas lines. Soon, yet another small-scaled, perfectly usable building will disappear from the purported intersection of “art and life” — raising the question of what Grand Center has in store for other smaller buildings in the district.

On the face, perhaps the doomed building is a tricky concoction to admire. Yet the turret and stone-faced town house that rises above an appended, plain red brick storefront is every bit as beautiful today as it was when built in the 1880s. The storefront is an added bonus, that could be utilized or removed depending on future plans. In sound condition and potentially eligible for National Register of Historic Places designation (likely if the addition came off), the house with storefront addition should be marketed as a redevelopment opportunity.

Grand Center’s streets are notably absent of the small-scale, affordable buildings that incubate small businesses, artists’ studios and apartments. These are the building types whose graceful practicality define areas like Cherokee Street and the Central West End, whose street-level vitality outshines Grand Center’s cycles of big-show and dead-empty. While Grand Center has improved a lot lately, much of that change comes from smaller spaces on Locust Street and in retail storefronts that have generated commercial activities long absent from the mix.

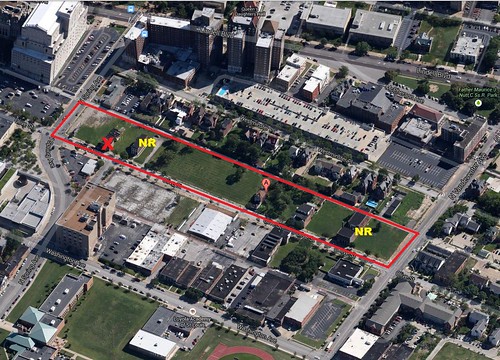

The 3700-3800 block of Olive Street is bereft of density, to be sure. From the Sim-City view, it may look like the sort of place to bulldoze and build again. Yet that approach would be utopian and short-sighted — although the view of cleared land from Spring to Vandeventer would be a very long, and anti-urban, view. Unfortunately, Grand Center has already started removing assets on this block, with nothing in their place to indicate demolition brings anything beneficial.

Rather than forecast utopian redevelopment, Grand Center might look at a building like 3808 Olive Street as an asset: a building with immediate economic utility, indelible architectural character and enduring contribution to a citywide sense of place. Neighbors of the building even include two buildings that are listed in the National register of Historic Places: the William Cuthbert Jones House (1886), designed by St. Louis architect Jerome B. Legg; and the former Lindell Telephone Exchange/Wolfner Memorial Library for the Blind (1899-1902), whose original Renaissance Revival front was designed by the not-so-insignificant firm of Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge. Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge also designed the Art Institute of Chicago (1893) and many other architecturally-renowned works in the US and Canada – a plus for a district that touts its concentration of works by important architects across time like Tadao Ando and William B. Ittner.

“Rightsizing†need not mean the casual removal of viable buildings on admittedly depleting blocks. Too often, however, that is how it is done. Effective rightsizing can be posing those remaining assets as catalysts for regeneration. In Grand Center, there is plenty of large-scale (ART), but not enough small-scale (LIFE) to make the district into anything approaching a real neighborhood. Retaining buildings like 3808 Olive Street and offering them for sale to small developers would be a step toward a compelling and complex urbanism.

Grand plans are invisible on vacant lots, and diminish feelings of safety as well as sense of place. Buildings are assets, even the small and weird ones. Buildings generate activities that tell people where they are –- and give them something to do. Grand Center needs these little buildings on Olive Street. The city can grow again, and we should not be throwing away any potential building block for our future.