by Michael R. Allen

The Chemical Building in 2005.

The Chemical Building in 2005.

Today’s news that the owners of the venerable Chemical Building at 8th and Olive streets have filed bankruptcy bring uncertainty to the future of their redevelopment plan. The welcome prospect that the name might not change to “Alexa” aside, the turn toward bankruptcy has some tongues wagging that downtown will have two big vacant buildings at the intersection for a long time. Diagonally across the intersection is the Arcade Building, now owned by a city agency after the Pyramid Companies declared bankruptcy and the building went to foreclosure auction.

Whether the molasses-slow market can absorb so much square footage of adaptively reused space is unknown. What is known is that taking a fully-occupied building like the Chemical and dumping all tenants before full financing is ready for rehabilitation is not a good idea (see also: Jefferson Arms). Had the developers waited, they might be waiting out the recession with a highly desirable low-rent refuge for small businesses.

The Union Trust Building today.

The Union Trust Building today.

No matter — the Chemical Building has an architectural history trump card that guarantees all is not lost. See, the as-built Chemical Building design by Boston-born Henry Ives Cobb triumphed over one by Chicago wunderkind Louis Sullivan. St. Louis was a remarkably receptive place for Louis Sullivan’s art, and the 700 block of Olive Street could have had side-by-side Sullivan. The Union Trust Building at 705 Olive had been completed in 1893, and its stunning round windows, exposed light well, terra cotta lions and monochromatic buff brick and terra cotta shaft all proudly brought Sullivan’s revolution to town. (The Wainwright Building of 1891 was no small achievement, but the local press took greater notice of the Union Trust.)

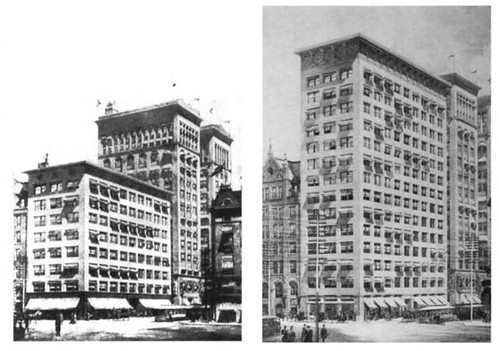

Two plans for the Chemical Building by Louis Sullivan, exhibited at the Third Annual Exposition of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1895.

Two plans for the Chemical Building by Louis Sullivan, exhibited at the Third Annual Exposition of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1895.

The Chemical National Bank planned a complementary, modern office building adjacent to the Union Trust. In 1894, the bank solicited the two proposals by Sullivan shown above. The difference between the two possible plans is primarily height; the gridded bodies are otherwise almost identical. With wide double windows, large round windows at the attic and a large overhanging cornice, the proposed buildings would have been very striking for both the time and place. However, their form certainly would have paled in comparison to the sheer genius of the Union Trust. Sullivan may have wished to touch his masterpiece with a gentler neighbor.

Instead of a gentle lesser work by Sullivan, the Chemical National Bank directors chose a rather bold 17-story design by Cobb. Cobb’s plan originally fronted only four bays on 8th Street, and was extended by five bays in 1903 from near-seamless plans by Mauran, Russell & Garden. Cobb’s building had a rather old-fashioned two-story cast iron base by Christopher & Simpson that was heavily ornamented in classically-derived foliated patterns. However, the upper floors were built out in a monotone of brick and Winkle terra cotta. The projecting trapezoidal bays, including a dramatic chamfered corner bay, emphasized the building’s height as much as the Union Trust’s piers. Yet the horizontal band courses dampened the effect of the bays, and the fenestration between the projecting bays was far from expressive of the building’s structural grid. The top two floors were clad in ornamented terra cotta.

Cobb tried to marry the Chicago School skyscraper with the nobility of traditional masonry ornament, and the result was panned in 1896 upon completion of the Chemical Building. With Sullivan looming next door, comparison was inevitable — and unfavorable. In 1896, an anonymous correspondent wrote in The Brickbuilder of the architect’s effort to express the Chemical Building: “He has left no quiet spot upon which we may rest the eye, and, although we may be awed by its great height, it lacks the simplicity and imposing grandeur of its neighbor, the Union Trust Building.”

The Chemical Building and the Union Trust Building, monochromatic neighbors from the 1890s.

Today, that assessment of the Chemical Building seems hasty. While Cobb’s work largely exhibits few progressive tendencies in an age of innovation — although it includes Chicago’s elegant Newberry Library (1893) — the Chemical Building is the architect’s strongest commercial design. The reference to Chicago’s long lost Tacoma Building by Holabird & Roche (1886-9) is obvious, but not the source of the Chemical Building’s design inspiration. Cobb could easily have mimicked Sullivan or other better-regarded luminaries of the Chicago School, but he chose instead to offer his own vision.

The Chemical Building’s red monotone is impressive and striking, and draws the eye toward itself with as much force as the Union trust or Wainwright. The Chemical Building is a fitting neighbor to the mighty Union Trust, and holds its own with a rather different statement about the tall building’s artistic potential. Together, the two buildings in their contrasting tones show us a full range of architectural imagination in the late 19th century. The Chemical Building’s horizons contrast effectively with the Union Trust’s swaggering vertical elements, reminding us that a tall office building is also a stack of floors where people work.

One without the other would be an incomplete range and, had the Chemical National Bank chose Sullivan to complete the block face to his measure, two of the same would not so powerfully urge the eye to fix on two powerful, beautiful masses. There is no doubt that the Chemical Building has good fortune on its side.