by Michael R. Allen

This is the fourth part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

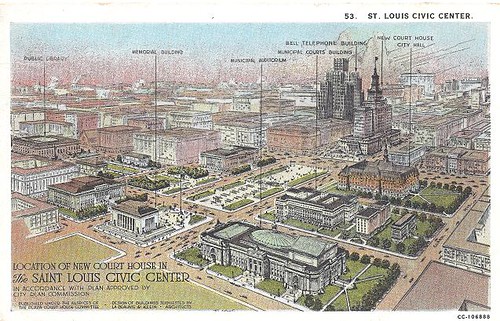

In 1919 the City Plan Commission published A Public Building Group Plan. The plan called for creation of green space on blocks between 12th, Market, 14th and Chestnut streets, with two blocks extending north to the Central Library on Olive between 13th and 14th Streets. The plan called the center spine between the library and the Municipal Courts building “the mall.” All around this park space would be new civic buildings, including a massive auditorium, a court house and others. To the west, a new plaza would be built across from Union Station. The plazas would be further adorned with fountains, an obelisk, and statues for a park environment devoid of nature fully designed as monumental space.

The title page of A Public Building Group Plan bore the name of the new City Engineer, Harland Bartholomew, whose persistence and commitment to City Beautiful principles breathed new life into St. Louis’ 15-year-old plan for a civic center. Bartholomew may not have authored every word, but his philosophy is evident throughout. In the introduction, the author states that “it behooves the city to so design its public buildings that these may faithfully and fittingly depict the civic spirit.” To Bartholomew, new public buildings were more than beautiful buildings in which government conducted affairs. These buildings were, at their best, symbols of civic commitment to imposing order and beauty on the urban condition. Bad public buildings were signs of urban chaos represented in St. Louis’ hodgepodge downtown fabric.

The report states that a public building group would be a monumental visual statement about St. Louis’ posture toward its physical fabric. In the report, a public buildings group is lauded as a “medium of good civic advertising†that would promote real estate development through property value increases on adjacent property. The civic center formed by a public buildings group would also become the “veritable heart of the city,” a place at which major traffic lines intersected and through which few human and vehicular traffic would not pass. This bustling depiction is not exactly what St. Louis would build.

The report’s pragmatic air underlies all of the triumphant language. Later on, the author makes clear that clearance of undesirable property was as much a goal of the civic center as was creation of an architectural city core:

Certainly the poor character of the majority of buildings between Twelfth, Eighteenth, Market and Olive streets is not merely a discredit to the city of St. Louis and an unpleasant daily reminder of the need for rehabilitation, but the present condition of this property represents a tremendous actual monetary loss to the city in the form of diminishing tax returns, which would be entirely overcome by the adoption and execution of the public-building group plan.

Not mentioned is that much of this real estate was owned and occupied by African-Americans restricted through the appalling racist practice of the St. Louis Metropolitan Real Estate Exchange from being able to buy property outside of the “exclusion zone” of downtown. The statement’s promise did not come to pass, as the real estate value was fairly static even after eventual construction of Memorial Plaza. Bartholomew’s words foreshadow the later appeals of developers seeking tax increment financing under Missouri’s postwar urban redevelopment law. Yet most development around the plaza would require public financing to complete.

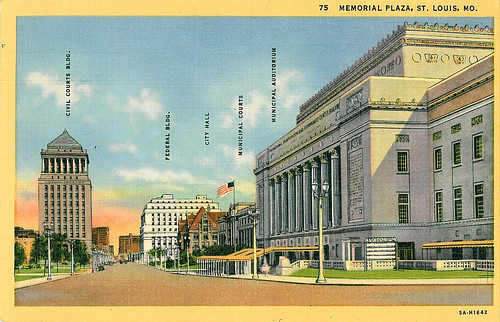

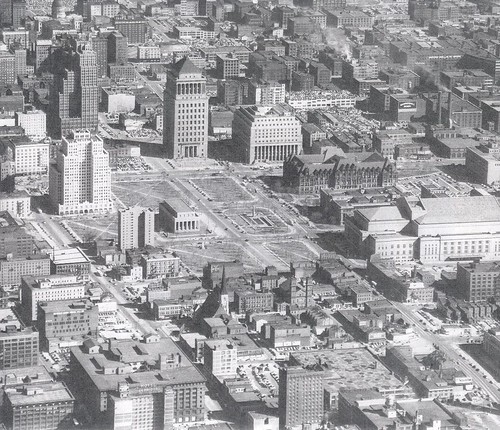

In 1923, voters approved the largest bond issue in the city’s history – an $87 million program of public improvements. Money for the civic center and all of its grand new buildings was included in several separate bonds. Major clearance and construction led to the grand transformation of western downtown anticipated since the turn of the century. The park plan put to bond issue created seven park blocks, with six grouped between Twelfth, Market, Fifteenth and Pine streets and a northern block between Thirteenth, Pine, Fourteenth and Olive streets. The collective park was named Memorial Plaza and dedicated to St. Louisans who lost their lives in the Big Parade of World War I. The center-most block was set aside for construction of a formal war memorial. This building would sit on an axis formed by the entrances of two existing civic buildings, the neoclassical Municipal Courts (1911, Isaac Taylor) on Market Street and the Italian Renaissance literary palace of the Central Library (1912, Cass Gilbert) on Olive Street.

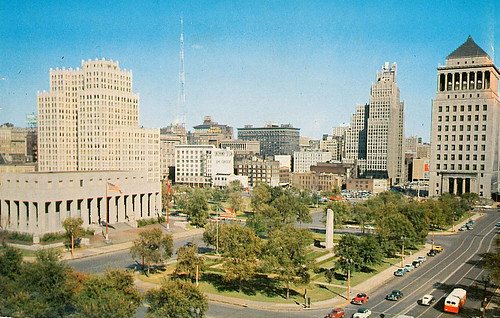

Not only did the bond issue offer the chance to build Memorial Plaza, but it included funds for completion of several major civic buildings to help form the long-anticipated group of public buildings. Upon passage of the bond issue, City Hall established the Plaza Commission to supervise the designs of these buildings. Contracts fell to different major firms, as was expected, and thus the buildings’ characters are not quite as harmonious as John Mauran and Harland Bartholomew had prophesized. The Civil Courts (1930, Kilpstein & Rathmann) at the east offered an eclectic tall visual anchor referencing the tomb of Masolaus, while its neighbor on the south was the streamline-Egyptian mass of the United States Courts and Customs House (1934, Mauran, Russell & Crowell). The Muncipal Auditorium at 14th and Market (1934, LaBeaume & Klein) freely mixed classical and Art Deco sensibilities, while the Soldiders’ Memorial at center (1938, Mauran, Russell & Crowell with Preston J. Bradshaw) brought a somber streamlined classicism heavier than its more eclectic neighbors. At the southeast corner, as it had been since before the idea of a civic center existed, was the older French Renaissance masterpiece of St. Louis City Hall (1898, Eckel & Mann with Harvey Ellis). Thus, Memorial Plaza’s wide views offered a visually and temporally discordant array of individually compelling works by the city’s major designers.

Memorial Plaza’s park blocks consisted of simple cross-plan paths and plantings of oak and other hardwood trees. The parks were ordered to reinforce the importance of the public buildings on users. There were few plantings, save short young trees, in the early years. The parks were subservient to the total vision of the public buildings grouping — pretty but static. Yet the purpose of these blocks was to serve as a memorial, so the visually simple character was appropriate. Decades later, upon maturity of the trees, the design intentions of the Memorial Plaza blocks seem very purposeful. Today Memorial Plaza is a well-defined and recognizable landscape.

In 1932, using funding from the bond issue, Aloe Plaza was completed across from Union Station. The park offered a stunning view of the terminal but little to do except gaze. The original modest landscaping plan for the plaza had consisted of trees planted around the perimeter of the block, and paired paths at center leading to and around a circular garden at the center of the block. Aloe Plaza was named for Louis P. Aloe, former president of the Board of Aldermen who had passed away in 1929.

In 1939, as part of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, an unrelated park was built between Market, Third, Chestnut and Fourth streets. This park was soon named Luther Ely Smith Square, after the attorney and civic leader who championed creation of the Memorial. To this day, this block is owned by the National Park Service although visually part of what became the mall. The Jefferson National Expansion Memorial itself consisted of huge park on the downtown riverfront, and should have been a warning of the future redundancy of more downtown green space. However, perhaps that redundancy was a small price to pay for the easy solution of land clearance. Downtown was aging and losing its businesses not just to other cities but to new suburbs. Parks — and parking for automobiles — were relatively easy and quick solutions for blocks of decaying buildings.

In 1940, the city added an amenity to the new park space by constructing Carl Milles’ controversial fountain The Meeting of the Waters on Aloe Plaza. The original plan was removed to make way for a new contour, which lowered the center of the block for a sunken plaza. In this plaza was the raised granite fountain base. The rest of the block was completed with a retaining wall at the north end and flared double paths leading outward from the fountain plaza to the east and west edges of the block. This formal plan remains intact, and the fountain is now a City Landmark protected under law.

As early as 1942, civic leaders began talking about the supposed need to connect Aloe and Memorial plazas with green space to “complete” the vision of the civic center. That year, the City Plan Commission released Saint Louis After World War II, a report whose recommendations included continuing downtown slum clearance and connecting the downtown parks with additional park space. Civic leaders and city government pushed for these new park blocks after the war’s end.

Part of the program for western extension of Memorial Plaza was construction of new housing — a vision that supplanted the civic center plan’s call for commercial real estate development. James L. Ford, Jr., Chairman of the Anti-Slum Commission established by the city, told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch in July 1945: “Our Plaza should be greatly enlarged and faced with decent and attractive multiple dwelling places located there by public or private funds [which] would offer an irresistible appeal because of its improvement over the old and its convenience to the life of the city.”

Yet St. Louis could not afford clearance with municipal funds alone. The 1949 federal housing act’s creation of federal loans for clearance of “blighted” areas allowed St. Louis leaders to contemplate financing of reconstruction of the area of downtown west of Memorial Plaza. The Ford Apartments at 14th and Pine, completed in 1950 and designed by Preston J. Bradshaw, did not utilize the new funds but inspired city leaders to undertake the larger Plaza Square project to the west.

Meantime, the city chartered the Urban Redevelopment Corporation (URC) to spearhead development of a four-block housing project bounded by Chestnut, 15th, Olive and 17th streets and a three-block extension of the Memorial Plaza between 15th and 18th streets. The Federal Home & Housing Authority gave the URC a conditional $2.6 million loan and $1.3 million grant so long as the city could pass a proposed $1.5 million bond issue to fund the Memorial Plaza extension. (The bond issue was predicated on retiring $825,000 in unspent Memorial Plaza bonds, making the overall debt to the city fairly low.)

The bond issue failed to pass in the March 1953 municipal primary election. Although the measure carried a majority, it did not meet a two-thirds requirement. The issue returned to a special election on September 29, 1953 and passed easily. The Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority began purchase of land and demolition in 1954, and the blocks were cleared by 1956. The park blocks were completed by 1960, with rather uninspired designs. Sixteenth Street was eliminated through the blocks, and Seventeenth Street made into a curved bend that dead-ended at Market Street. The landscape designs consisted of irregularly groups trees, meandering paths and — the most interesting components — formations of concrete and stained glass screens around sculptural metal fountains.

These blocks were wider than the earlier blocks and visually plain. Yet they opened views of the civic buildings and allowed for more clearance of the run-down shops of Market Street. Memorial and Aloe plazas consequently lost some of their visual impact as they were subsumed into the larger mall. The eventual completion of Plaza Square Apartments (Hellmuth, Obata & Kassabaum with Harris Armstrong) in 1961 added 1,090 residential apartments on four blocks north of the mall. Plaza Square’s landscape integrated well into both the Memorial Plaza green space and into the older commercial fabric to its north and west. However, the City Plan Commission’s prophecies of tall new buildings floundered as St. Louis struggled to maintain development interest in downtown.