by Michael R. Allen

This is the fifth part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

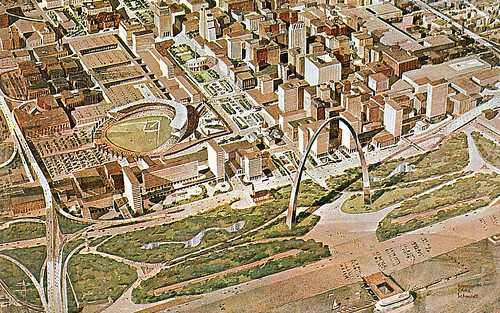

Selection of Eero Saarinen and Dan Kiley’s plan for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial design in the 1948 design competition drew planners’ attention to eastern downtown. In 1954, the architectural firm Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen published a rendering of an eastern park mall running from the Civil Courts and terminating at the new Memorial. The block between Third (now Memorial Drive) and Fourth Streets would be landscaped by the National Park Service as part of the Memorial and named Luther Ely Smith Square. The firm’s rendering was the first time that the idea of extending the downtown park system to the east had been considered.

The rendering by Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen coincided with creation of the western blocks between Fifteenth and Eighteenth streets between 1954 and 1960. Those blocks joined existing Memorial and Aloe plaza blocks to form a mall-like line of parks from Twelfth Street (later Tucker Boulevard) west to Twentieth streets. The new Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and Luther Ely Smith Square shaped an eastern terminus for the larger park project that would soon be named the Gateway Mall.

Yet the Civil Courts Building and the Old Courthouse were obstacles to a continuous park mall. Still, the rendering of formally symmetrical park space joining the existing Memorial Plaza and park mall at the west to the Memorial at the east was immediately popular. Anticipating timely completion of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, downtown business leaders wanted to reconstruct eastern downtown with a modern built environment worthy of a major international landscape.

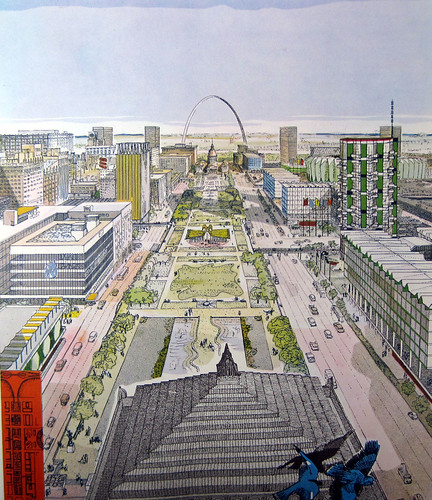

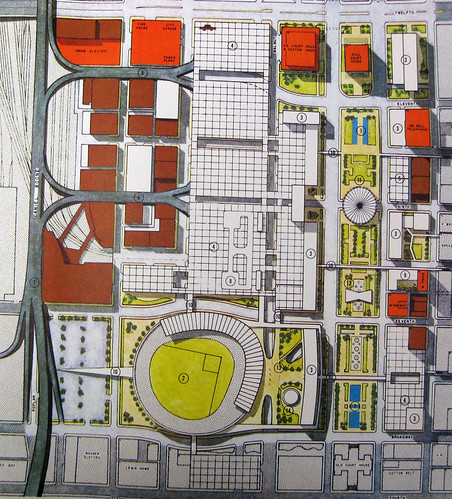

In 1960, the City Plan Commission adopted A Plan for Downtown St. Louis. The plan included the first official endorsement of eastern extension of the park mall, named — perhaps in unwitting homage to the 1912 plan — the “Parkway.” The Parkway was envisioned by delineator Erwin Carl Schmidt and architect Kurt Perlsee, then employed in the office of the Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen. The firm’s principal Arthur Schwarz was serving on the City Plan Commission at the time.

According to the 1960 downtown plan, the Parkway was “formal in concept, yet human in detail” and would start at the Mississippi River and run west to Twentieth Street. The plan is emphatic that the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial would be a component of the park mall. This concept would be discarded in the future, as seen by the disconnect between the Gateway Mall Master Plan of 2008 and the Framing a Modern Masterpiece design competition.

Perlsee’s renderings suggested creating park blocks east of Twelfth Street that indeed were formal, with wide central lawns and uniform tree plantings, but also humane. The sides of the park blocks could be built up with modern buildings drawn with suggestive whimsy, and the central element between the Old Courthouse and the Civil Courts Building would be a Music Hall built in place of a removed Ninth Street. Perlsee’s Music Hall consisted of a stylized thin-shell drum, tilted up toward the Gateway Arch. Alas, this playful structure would never be built, but Perlsee’s firm would be responsible for an iconic, round mid-century modern work: the Philips 66 gas station at Council Plaza, designed by Richard Henmi and completed in 1967.

A Plan for Downtown St. Louis was the first document that established the concept of a park mall extending west from the riverfront to Twentieth Street. City officials and downtown leaders would carry this goal forward for the next few decades, with mixed results. The ensuing patchy implementation would not live up to the promise of the 1960 plan.

In 1962, voters approved a $2 million bond issue to build the first part of Kiener Plaza on the block between Broadway and 6th streets just west of the Old Courthouse. The block was developed in the next three years with a circular fountain at west with a central path and two curved approaches at the east. Inside of the fountain on a pedestal would be William Zorach’s sculpture The Runner, placed with the runner figure facing west. However, a $6.2 million November 1965 bond issue to fund construction of the rest of the mall — to which city officials expected a substantial match of federal funds – was rejected by voters.

One reply on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 5): The 1960 Downtown Plan”

The third image of downtown St. louis would have been nice. Thank God they did not build the Music Hall! That would have been awful!