by Michael R. Allen

This is the sixth part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

In March 1966, an undeterred Mayor Alphonso Cervantes traveled to New York City for the public announcement of a national design competition with a $15,000 prize for a master design for the entire Gateway Mall. The city and Downtown St. Louis, Inc. sponsored the design competition. Fifty-seven firms or individuals submitted designs before the winner was announced in June 1967.

The boundary of the competition was set with the Old Courthouse at the east and the proposed North-South Distributor (roughly Twenty-Second Street) at the west. the competition was the first attempt at a master plan for a landscape that was merely six years old in the minds of planners. By this time, downtown had lost so much building stock and street life that the old rationalist rhetoric about alleviating the ills of the central city would have been ludicrous. Instead, Cervantes and civic leaders began to talk up the effect of the Gateway Mall as an instrument that might lead to building up the core. With the Mall extended, they argued, Chestnut and Market streets would become desirable sites for the sorts of large corporate headquarters St. Louis desperately wanted to attract. The rhetorical emphasis shifted from social to economic benefits, but the rationalist framework remained latent.

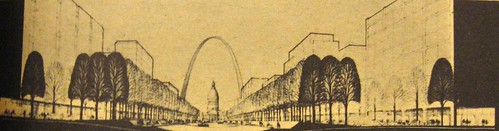

Just as before, there was a slight problem: every block targeted for the mall contained buildings. These blocks were marked by storefront buildings and office buildings, most occupied. The only problem with many was a need for repairs typical of old buildings. However, the winning proposal in the competition by Sasaski, Dawson & DeMay of Boston did not include retention of a single building in the path of the new mall path. Sasaski, DeMay & Dawson called for yet another major change to the mall design. Here, the blocks would be landscaped to form a depressed center lawn. Large berms would separate this lawn from four rows of trees on each side. The plan’s design program hinged on landscape symmetry that framed views of the Old Courthouse, Arch and Civil Courts Building. In the same stroke, the architects’ quest for the wide view brought neglect the importance of human activity to healthy parks.

However, the designers tried to avoid the shortcomings of the City Beautiful park planning by including new shops on Chestnut and Market facing the mall in the recessed ground-floor arcades of anticipated new buildings. Sasaki, Dawson & DeMay realized that the park space needed constant day time pedestrian traffic to be active. The firm even includes revision of the Memorial Plaza area to include sunken flower gardens on blocks around the Soldiers’ Memorial.

Other ideas in the winning proposal have become perennial. The plan called for a major tall office building west of Twentieth Street atop the depressed lanes of the would-be North-South Connector. This tall building would be a “visual termination at that end.” The idea of a tall office building terminating the western end of the mall resurfaced in 2009 in the Northside Regeneration proposal presented by developer Paul J. McKee, Jr. The other idea that the landscape architects presented that has resurfaced was the idea of building a two-level underground parking garage beneath the six eastern blocks of the mall. This garage would have been directly connected to the depressed lanes of Interstate 70 by ramps. Most recently, the design competition for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial has revived discussions about putting parking under some of the Gateway Mall.

Oddly, city leaders made little attempt to fund the ambitious large plan. The Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority finally obtained a federal grant for land acquisition and park construction. After acquiring one block, between Tenth and Eleventh streets, and implementing a greatly simplified version of the Sasaki plan there in 1976, civic leaders abandoned the latest design after negative public response. Soon after, the completed block was graded and redesigned as the site of Richard Serra’s sculpture Twain.

3 replies on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 6): The Design Competition of 1966-1967”

looking forward to the rest of this series!

Didn’t the City receive money from State tax credits to

build an underground parking garage in the Mall, then, not having built the

garage, was forced to repay the State with interest?

Â

Found some articles referring to this.

Â

Â

St Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) | February 28, 1999

Prost, Charlene

Â

“Years after most everyone thought the Gateway Mall

downtown was done, turns out they were wrong.

Â

To repay the state in part for $8.7 million in tax breaks

it gave to five corporations that contributed money to finish the mall in 1993,

a city agency was supposed to build underground parking in the mall within five

years. On top of that, $2.75 million of revenue from the parking was supposed

to go back to the state.

Â

But the parking facility was never built. And nobody at

City Hall can explain why.

Â

State officials want the $2.75 million, with interest.

And they want the parking, either beneath the mall as promised or perhaps

somewhere else, to resolve parking problems for about 690 state employees

working in the renovated, historic Wainwright building adjacent to the mall.

Â

Â

Â

Â

St Louis Post-Dispatch (MO) | October 16, 1999

Bell, Kim

Â

In 1993, the city got state tax credits to help finance

an underground garage downtown. It now must pay back about $3.6 million.

Â

St. Louis never followed through with an idea in 1993 to

build an underground parking garage as part of the Gateway Mall, the stretch of

green space downtown between Market and Chestnut streets.

Â

So on Friday, the Board of Aldermen agreed to pay a $2.7

million promissory note to the Missouri Development Finance Board because the city

defaulted on its plan.

Â

Aldermanic President Francis Slay said that with

interest, the $2.7 million promissory note from six years ago had grown to $3.6

million.

Â

Whoa. Sorry about the formatting – cut and paste disaster.