by Michael R. Allen

On April 24, after a tornado struck Lambert Airport, the New York Times published the article “Struggling St. Louis Airport Takes a Shot to the Chin, but Recovers.†While many St. Louisans quibbled over the symbolic image of the city encapsulated in the adjective “struggling†(applied to only the airport), I found a less immediate semiotic matter of interest. Namely, the article was accompanied by a striking color photograph of Lambert Airport’s iconic main terminal (1956) in the background behind architect Gyo Obata, who directed the project for the firm Hellmuth, Yamasaki & Leinweber. Obata is the last living link to the firm and its renowned principal Minoru Yamasaki, and his presence in the photograph of a boarded-up, weather-beaten terminal conveys strong pride in its design and concern for its future.

In Camera Lucida Roland Barthes writes about the punctum, that part of a photograph’s meaning “that pierces the viewer.†The punctum is subjective, and may diverge from any obvious or intended symbolism in an image. In that New York Times photograph, showing the architect’s watch over a damaged part of Yamasaki’s modernist legacy, I quickly noticed my punctum, a place not represented directly in the photograph but so immediately present in my mind: Pruitt-Igoe.

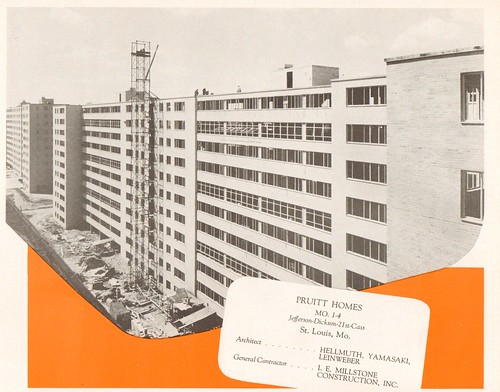

Of the building actually present in the photograph, the iconic work of fantastic thin-shell concrete forms, Obata told the newspaper that “[w]e were really out to create the imagery of St. Louis.†Indeed, this is true, because the airport terminal has become an indelible symbol of the city both at home and away. Yet Lambert cannot be divorced from that other original, wholly modernist St. Louis project by Yamasaki and his designers built at nearly the same time as the Lambert terminal. With the thirty-three towers of Pruitt-Igoe, Yamasaki wrought upon St. Louis a project that replaced an entire neighborhood with a massive an unprecedented scale and size of modern architecture. Long before Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch defined the city’s identity through modern architecture, and contemporary with the Lambert Terminal, the Pruitt and Igoe homes became St. Louis’ largest and most daring entrance into postwar design.

“Nothing will hurt that structure,” Obata rightly said of the Lambert Terminal after its brush with the tornado. Our city’s planners, social scientists, political leaders, builders and architects conferred a similar wish upon Pruitt-Igoe at its birth. Like Lambert, Pruitt-Igoe was at its core made of strong reinforced concrete. While the linear, intimidating forms of the towers were heavy compared the Lambert’s lightness, they were no less well-built and, despite some unfortunate modifications, not essentially less well-designed. The Pruitt-Igoe towers met acclaim across the architectural world and in the press. In the eyes of the world, for just awhile, St. Louis could very well have been Pruitt-Igoe. (Or, of course, Lambert Airport’s Main Terminal.)

Yet architecture is nothing if not for its utility, and many well-built, well-designed and beautiful buildings have fallen in absence of a practical or immediate use. Pruitt-Igoe’s problems begin in the complex dynamics of whether the towers’ design actually met their necessary patterns of use as housing. That question is complex, and I won’t delve into it here. Suffice to say that as Pruitt-Igoe fell prone to disrepair — as it was “struggling” — no architect elected to be photographed in front of one of its towers for the press. The architectural figure who did appear at the end was Charles Jencks, who famously proclaimed that the demolition of the towers between 1972 and 1977 was the “death of modernism.” Okay, but what of Pruitt-Igoe itself? What of St. Louis’ building a monument to social and architectural ideals of the modern era, designed by an architect whose significance is international, and then destroying that monument before most of its buildings had even become twenty years old?

I am not promoting preservationist nostalgia for the towers of Pruitt-Igoe, but wonder what could have happened had an architect of Gyo Obata’s stature – even Yamasaki himself! – stood by Pruitt-Igoe in its darkest hour. Even if the towers had still fallen, could the architectural profession then been able to take ownership of Pruitt-Igoe? My colleague Nora Wendl aptly summed up the fate of Pruitt-Igoe as “capital punishment for architecture.†Pruitt-Igoe had no defense, only Jencks’ charged and influential post-execution sentencing. Pruitt-Igoe’s site has even been left as an unmarked grave. Meanwhile, the last tower at Cochran Gardens, Pruitt-Igoe’s smaller and better-loved high-rise predecessor in St. Louis, is about to fall, removing that trace of the legacy. Thus I look at a simple newspaper photograph of Obata at Lambert terminal and envision Lambert’s shadow, lost but perhaps some day to be found.