by Michael R. Allen

I provided this essay for the brochure that was distributed at Modern STL’s Harwood Hills House Tour on May 19, 2013.

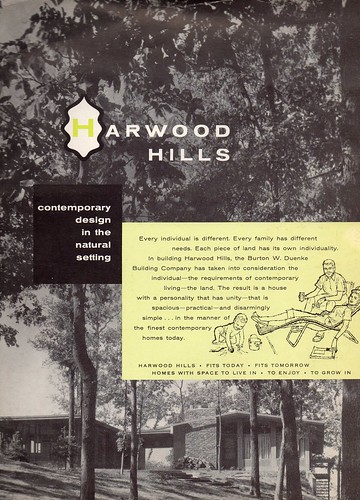

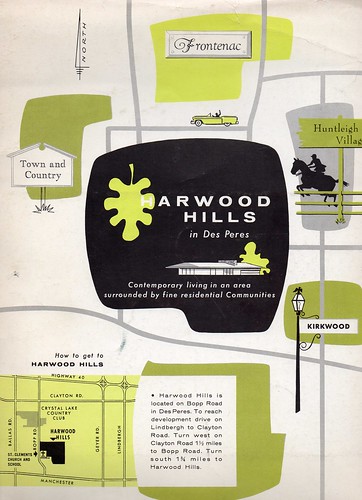

The brochure used to market Harwood Hills epitomizes the claims that drove St. Louis’ mid-century suburban expansion in its subtitle: “contemporary design in a natural setting.” Influences as wide as Mies van Der Rohe’s Farnsworth House, Cliff May’s California ranches and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Usonian houses widely influenced modern ranch houses built in St. Louis County in the 1950s, with a uniting principle being minimalism in design set against largely untouched natural sites. Builder Burton Duenke, developer of Harwood Hills, embraced these principles again and again in developments that include Arrowhead, Ridgewood and Craigwoods. Collaborating with architect Ralph Fournier for most of these projects, Duenke built some of the County’s strongest enclaves of mass-produced residential modernism. Today, Duenke and Fournier’s collaborations are widely held to be the finest examples of “subdivision modernism” in the region.

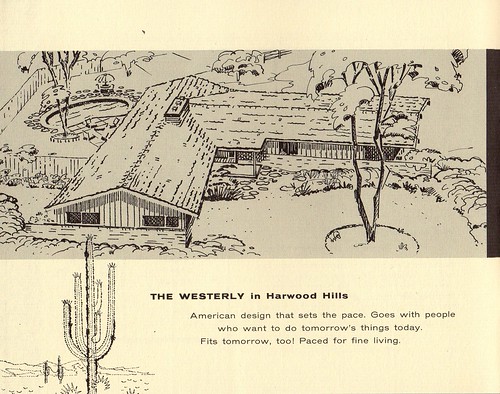

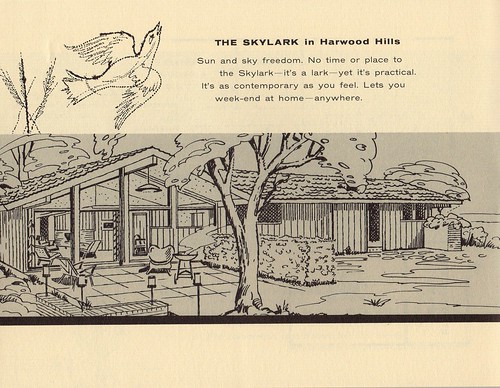

The designs found in Harwood Hills meld the California ranch aesthetic — the long, low forms with low-pitched gable roofs — with the open planning found in Wright’s small houses as well as larger homes by William Bernoudy, Isadore Shank and others. The Skylark seems to be appropriated from the streets of USONIA, while the larger two-level Fairways sits nicely among designs by Shank and Harris Armstrong. Fournier’s influences are wide, but his authorship is evident. Each of the homes in Harwood Hills has a resolute economy of plan that produces extremely balanced and proportional forms. Harwood Hills’ houses endure because they advance the classical principles of architecture eternal instead of simply copying dominant modern forms. The “cookie cutter” stamped out other houses, but none here.

Leaving detailing to owner discretion led to a polyglot vocabulary here; not every house is modernist in exterior treatment. Still, even decorated houses have spare bodies emphasizing horizontality and material over style, and the plans are as modern as any else here. The genius of Fournier’s planning is evident in the provision of large, open living and dining areas, attached garages, open utility space that could later be finished, and (in the two-level designs) space for future expansion. Moreover, each house is emphatically tied to nature through ample windows in the public rooms and provisions for patios that allowed nearly year-round outdoor living. All of these characteristics are sought after by families today, making the demolitions here all the more strange.

Modernism in St. Louis County

World War II slowed American construction considerably, but immediately after the war the nation entered rapid suburban growth. The victorious nation threw itself into remaking itself, giving itself a new image for new times. Mass construction spurred by the 1948 federal home loan guarantee program allowed for the triumph of modernist design in St. Louis County.

According to architectural historian Eric Mumford, “by the mid-1950s, modern architecture had become the norm in St. Louis” with construction especially high in St. Louis County. This reflected the national acceptance of Modern architecture. Webb writes that “in the 1950s, most progressive architects took modernism for granted—it was Local interest in non-derivative design was not widespread before the war, when most new houses built in St. Louis County were built in revival styles. However, after the war architects in America began to implement the influence of the International Style, the Prairie School and other modern schools of architectural thought.

The hallmarks of new design were minimal detailing as opposed to referential ornament, asymmetry as opposed to formalism, use of mass-produced hardware and building materials as opposed to custom-built items. The Modern Movement had roots in early twentieth century designs that, according to historian Esley Hamilton, “rejected the popular historical styles of the time, in fact the whole idea of styles.” Mid-Century Modern Architecture in St. Louis County: Outstanding Examples Worthy of Preservation includes 35 houses built between 1935 and 1961. According to Hamilton, interest in Modern architecture in St. Louis County began in the 1930s and dwindled in the 1970s. By then Harwood Hills was fully developed.

The Teardown Threat

Today, preservation of Harwood Hills raises some challenges in local policy that are yet unresolved. In suburban neighborhoods across the nation, the current crisis is known as the “teardown.” Speculators or homeowners have targeted mid-century ranch houses because of their large, naturally-attractive lots and the stability of their surrounding areas. Armed with a questionable rationale — that these houses are too “small†or “inefficient†– and the support of the real estate community, those who tear down mid-century modern homes often remove more than just one building. In St. Louis, famous “tear downs” include Samuel Marx’s spectacular International Style residence for Morton D. May (1941), lost in 2004.

However, most lost Modern houses are noted less in their individual removal but in their cumulative absence. This impact mirrors national trends. For instance, reports from California last year suggest that Eichler houses are at risk for mass disappearance in Palo Alto and elsewhere. From Tulsa to Philadelphia, small modern houses that compose leafy, human-scaled places are falling for often over-sized and insensitive new buildings. Of course, houses are only part of ongoing deliberations over how to protect the nation’s vast array of modernist buildings and structures. To date, the easy consignment to rubble of major works by designers like Richard Neutra and Bertrand Goldberg gives one pause. Protecting ranch houses by regional architects and homebuilders is an even taller order – but one that holds communities together.

Tear downs actually are not that different from waves of demolition that have damaged historic neighborhoods in the city. Across St. Louis, houses have disappeared one at a time until entire block faces barely resemble anything historic. However, in the city usually demolition leads to vacant lots while in the County demolition leads to incompatible new houses. Both rob historic landscapes of their integrity. Demolition can disqualify neighborhoods from attaining historic district status at the local or state levels. Without such status, regulating demolition and using historic tax credits are impossible – making it likely that more will be lost. Teardowns can lead to dismissal of vast areas of important modern residential architecture because the general appearance is no longer visually cohesive.

At Harwood Hills, there’s still a chance to stem the tide despite what has happened in recent years. The start to all preservation efforts is education, which is why this year’s house tour is significant for the neighborhood’s future. However a vital second factor is legal protection of the remaining historic houses. Until Des Peres enacts a historic preservation ordinance, there will be no local demolition or design guidelines. Lest one judge Des Peres harshly now, consider that only nine of St. Louis County’s 91 municipalities have any preservation ordinances and that there is no regulation in unincorporated areas. Harwood Hills’ plight is not isolated, but sadly is part of the norm.

Harwood Hills reminds us that we are not doing enough to create frameworks that protect our abundant and ever-beautiful modern residential fabric. Fournier’s designs are eminently rich with details and concern for siting, natural light, layout and material harmony. These traits are not exhausted by today’s concerns for energy efficiency and modern kitchens and bathrooms. Instead, Fournier’s designs have a resilient vocabulary that can and should be adapted by new owners. Harwood Hills could be at the forefront of raising County preservation standards to the level of design seen in its threatened resources.

More Harwood Hills photos are online here.