by Michael R. Allen

Although heavily deteriorated, and possessed by a shadowy real estate speculator, the lonely large residence at the southwest corner of Cook and Whittier avenues remains a stunning example of local Richardsonian Romanesque residential design. The house was built around 1892, with its definite architect a mystery and its origin enmeshed in a design exercise whose details are also elusive. Underneath a high-pitched slate-clad hipped roof with dormers is a two-story brick building on raised basement. A curious corner bow is open at the second story, framed by Iowa sandstone elements and rising to an intersecting rounded hip.

The same sandstone frames the main entrance, raised high above steps, facing Whittier Avenue. At the first floor facing Cook Avenue is a wide segmental arched opening with vertical headers traced by an archivolt. Rusticated sandstone at the base and smooth sandstone forming a belt course and window surround give the building further eclectic expression. Other details on the exterior can be savored without further explanation, but the interior — once of equal intrigue — has been ravaged by abandonment.

The origin of this substantial residence is slightly diffuse, but some facts are known. Pension and claim attorney Frederick W. Fout (1839-1905) developed this house as part of Fout Place, a block of five substantial dwellings occupying a large corner lot in the fashionable area northwest of Midtown. In The Architecture of the Private Streets of St. Louis, Charles W. Savage discusses the 1892 publication of several sets of designs for these buildings by renowned architects in Northwestern Architect and American Architect. Savage speculates that the designs came out of an “sporting exercise” among architects to develop designs for the site, perhaps to encourage Fout to use a trained designer.

Oscar Enders submitted “A Block of Houses for Captain F.W. Fout, St. Louis, 1892” for the office of William B. Ittner. Architect Harvey Ellis, designer of the Compton Water Tower, submitted “Premises of Frederick W. Fout, St. Louis,” consisting of several Richardsonian dwellings with high, dormer-punctured hipped roofs. One building has a picturesque round tower with conical roof. The esteemed firm of Barnett, Haynes & Barnett, architects of the Cathedral Basillica among many other notable works, submitted partner Tom P. Barnett’s French Renaissance plan for “F.W. Fout’s Terrace, St. Louis, Mo.” The roof forms, round tower and employment of round arches found in Ellis’ plan are also seen in Barnett’s. Likely Fout borrowed from the submitted designs to draft his own plans for the houses. Known is that Fout did not hire any of the architects who published plans.

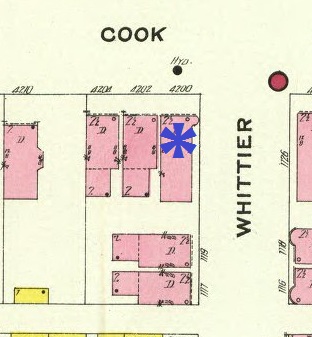

In the end, Fout constructed the massive and ornate corner building with two paired town houses at the west and two at the south. This was all investment property, and Fout never lived here. The Sanborn fire insurance map of 1909 shows that the footprints suggest the neighboring dwellings were far less impressive than the corner building, and of a conventional plan. These buildings could not have adapted the high-style plans published in the journals, but certainly were informed by them. Barnett’s rendering did include two buildings in the background similar to the subordinate members of the group, so perhaps Fout had always intended to use the designers to generate ideas rather than real plans.

An 1893 article in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on the death of Charles D. Terrill shows a unique connection between the site of this house and the life of a colorful veteran. In 1862, Terrill had enlisted in the Union Army’s Company G, First Maine Heavy Artillery, and had served until 1864. In 1891, he asked fellow Civil War veteran Fout if he could reside in a pitched tent at the Cook and Whittier property. Fout granted the man use of the site for one year, until he built the house that stands there and its lost neighbors. Terrill told Fout that he had not slept under shingles for 30 years, and refused to dwell in the houses under construction when the chance was offered.

The dogged veteran slept in a hole dug under his tent in the winter, insisting that he was “a soldier” and could handle the conditions. At the time of his death, Terrill was claiming land on the Cherokee Strip. The winters the stoic soldier passed on Cook Avenue were spent under the stars on open land. Today, the scene is again opening up with a wide view of the night sky. Current owner of the residence Urban Assets LLC’s lack of stewardship sadly portends that the house at Cook and Whittier will be gone in short time, leaving a wide open camp site once more.

(Note the last year that Uban Assets LLC paid the land tax on the property was 2009. If Urban Assets fails to pay the land tax in 2012, the Sheriff of the City of St. Louis will place the property into one of the city’s Land Tax Sales, which would be may 2013 at the soonest.)

3 replies on “Fout Place Fading Away at Cook and Whittier”

looks like Detroit

This kind of thing breaks my heart. I’ll bet that was a gorgeous house once upon a time, and no one will build something of such substance and beauty ever again. Now, instead of brick and sandstone we get drywall and load-bearing Tyvek. I’m holding on to my 1919 Craftsman as long as I can.

What a beautiful place. The brickwork is stunning. It’s very sad to see such a fine place in such hopeless shape.