by Michael R. Allen

On June 3, the Planning Commission unanimously adopted a resolution to grant demolition of the corner commercial building at 5286-98 Page Boulevard if owner Berean Seventh Day Adventist Church met several conditions. Those conditions are completion of permit-appropriate construction drawings for the proposed surface parking lot within 30 days and securing of construction financing within 90 days. If those dates are not met, the permit stands denied and the church will have to appeal the denial to the St. Louis Circuit Court.

On June 3, the Planning Commission unanimously adopted a resolution to grant demolition of the corner commercial building at 5286-98 Page Boulevard if owner Berean Seventh Day Adventist Church met several conditions. Those conditions are completion of permit-appropriate construction drawings for the proposed surface parking lot within 30 days and securing of construction financing within 90 days. If those dates are not met, the permit stands denied and the church will have to appeal the denial to the St. Louis Circuit Court.

How did the demolition permit end up at the Planning Commission, and why would that body approve demolition for a parking lot? In January 2008, the Preservation Board upheld Cultural Resources Office staff denial of the demolition permit by a vote of 5-2. Per city preservation law, Berean appealed this decision to the Planning Commission. The next step in the appeals process would be court. The Planning Commission has authority to review and “modify” decisions of the Preservation Board, which is what the June 3 decision is considered. (Note that the Planning Commission does not typically solicit or accept citizen testimony, although the public may attend its meetings.)

At the behest of the Planning Commission, the Berean church worked with Dale Ruthsatz at the St. Louis Development Corporation to improve the original plan for a parking lot. The new plan calls for “green” features such as permeable paving and landscaping. Parking entrances have been moved off of Page and Union and onto the alley, so that pedestrians on these streets won’t be bothered by traffic. Eventually, the church wants to build a community center on the site. Planning Commission members expressed the sentiment that they wanted to exercise leverage over the parking lot design rather than let the matter go to court where the city might lose its case and its design review.

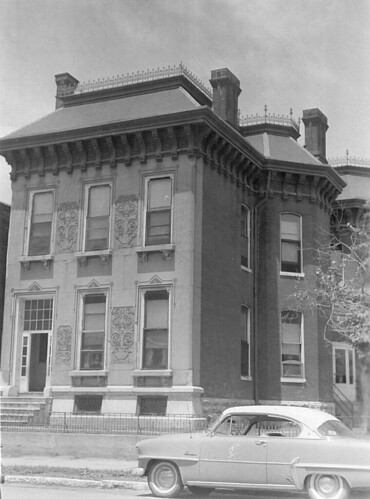

Back in April, the Planning Commission also overturned — or, rather, modified — the Preservation Board decision on a certain house at 2619-21 Hadley Street. The back story is slightly complicated. Suffice to say that the Haven of Grace, a shelter for homeless pregnant women, wanted the old house gone — after it had resolved to rehabilitate it in order to secure a demolition permit for another historic building.

Back in April, the Planning Commission also overturned — or, rather, modified — the Preservation Board decision on a certain house at 2619-21 Hadley Street. The back story is slightly complicated. Suffice to say that the Haven of Grace, a shelter for homeless pregnant women, wanted the old house gone — after it had resolved to rehabilitate it in order to secure a demolition permit for another historic building.

The Haven of Grace pursued demolition relentlessly. After the Preservation Board in August 2008 reaffirmed its original decision, the organization appealed to the Planning Commission. The legal strategy of the Haven of Grace was effective enough to lead to the Planning Commission’s vote to overturn the Preservation Board decision, but not enough to do so without penalty. The Planning Commission stipulated that the Haven of Grace must pay $25,000 to city that will be used for building stabilization by the Cultural Resources Office.

While there are few chances for the city to secure $25,000 for stabilization, the Planning Commission action may be a dangerous precedent. My hope is that it is an isolated instance of such a questionable outcome. It’s certainly better than a victory for demolition with no trade-off.

The house on Hadley Street is now gone. Watching the demolition, it was clear to me that the house was in much better condition that I had assumed. The floors looked sturdy, original millwork abounded and even the plaster walls looked to be in fair condition. An expenditure of $25,000 could have mothballed this house for better days.

The house on Hadley Street is now gone. Watching the demolition, it was clear to me that the house was in much better condition that I had assumed. The floors looked sturdy, original millwork abounded and even the plaster walls looked to be in fair condition. An expenditure of $25,000 could have mothballed this house for better days.

The Planning Commission’s compromises demonstrate the flaws in our current system or preservation review and planning. In fairness to the Planning Commission, the city lacks progressive ordinances here. I understand the inclination toward meting out compromise rather than take matter into lengthy circuit court battles. However, if the Preservation Board’s decisions on these matters were made fairly and by wide margins of voting members, they should be upheld on appeal.

The Planning Commission should not feel trapped. The Preservation Board should not be rendered powerless because an applicant (or elected official) has the money and time to make things difficult for the city. We need better design ordinances and city agencies empowered to do more than just say “no.” Ultimately, we need a better framework in which to make planning decisions.