by Michael R. Allen

Six Case Studies in Freeway Removal is a an excellent overview of successful efforts to eliminate interstate highways in urban areas that created barriers. While there are examples from large cities like San Francisco, Toronto and Vancouver where one might expect progressive government, there are also studies from Milwaukee and Chattanooga where advocates for reconnecting the urban fabric faced greater odds.

Six Case Studies in Freeway Removal is a an excellent overview of successful efforts to eliminate interstate highways in urban areas that created barriers. While there are examples from large cities like San Francisco, Toronto and Vancouver where one might expect progressive government, there are also studies from Milwaukee and Chattanooga where advocates for reconnecting the urban fabric faced greater odds.

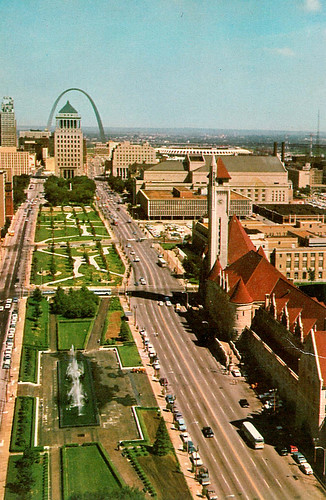

There are constant themes in each project profiled in Six Case Studies in Freeway Removal: beautification and functionality were major goals of cities that removed freeways or freeway sections, spillover traffic was absorbed without major new congestion and freeway removal almost always lead to higher property values. St. Louis leaders contemplating the mess at the western edge of the Gateway Arch grounds ought to consider the findings of this study, and commission one aimed at the particular local problem that I-70 poses.

One of my first reactions to the case studies from other cities is that the I-70 problem is not that big. Taking the logical dimension of removal from the Poplar Street Bridge on the south to Cass Avenue on the north, one sees that we don’t have as long or as vital a stretch of highway as other cities removed. What we will have in a few years, after the new river bridge opens, is a redundant second section of an interstate highway that disrupts the connection between downtown and the riverfront.

Is St. Louis ready to join the ranks of the cities that have found the leadership needed to think big? A few months ago, I might have been pessimistic. Now, I see that City Hall and many leaders are willing to take a major urban planning risk with McEagle Properties’ NorthSide project. Putting aside the details of NorthSide, that project takes a leap of faith — the scope is vast, the cost great and the potential for changing the central city tremendous. Part of the project even involves removing interstate highway infrastructure, the 22nd Street ramps connecting to Interstate 64. The project aims to capture southbound I-70 exit traffic and send it onto Tucker Boulevard, not eastward toward Memorial Drive. That flow could lessen traffic volume on the old I-70 and Memorial Drive.

Is there a connection between NorthSide and removal of I-70 downtown? Not yeat, but there is a binding tendency in each project: big-picture economic development planning. While NorthSide’s proponent is its developer, proponents of removing I-70 are citizens who see tremendous development opportunity along a human-scaled street. The removal of I-70 would weave the riverfront back into downtown, and it would create acres of land ripe for transformative downtown development. Like NorthSide, the process could take decades, but the results would be redevelopment on a scale beyond our wildest dreams. Add in the Chouteau Greenway project, and in thirty years Downtown could be ringed not by bleak interstate, asphalt parking and towing lots and vacant buildings but by connections to exciting new projects and renewed old neighborhoods.

Is there a connection between NorthSide and removal of I-70 downtown? Not yeat, but there is a binding tendency in each project: big-picture economic development planning. While NorthSide’s proponent is its developer, proponents of removing I-70 are citizens who see tremendous development opportunity along a human-scaled street. The removal of I-70 would weave the riverfront back into downtown, and it would create acres of land ripe for transformative downtown development. Like NorthSide, the process could take decades, but the results would be redevelopment on a scale beyond our wildest dreams. Add in the Chouteau Greenway project, and in thirty years Downtown could be ringed not by bleak interstate, asphalt parking and towing lots and vacant buildings but by connections to exciting new projects and renewed old neighborhoods.

Other cities took the leap of faith needed to set this level of vision into motion. Will St. Louis?