by Michael R. Allen

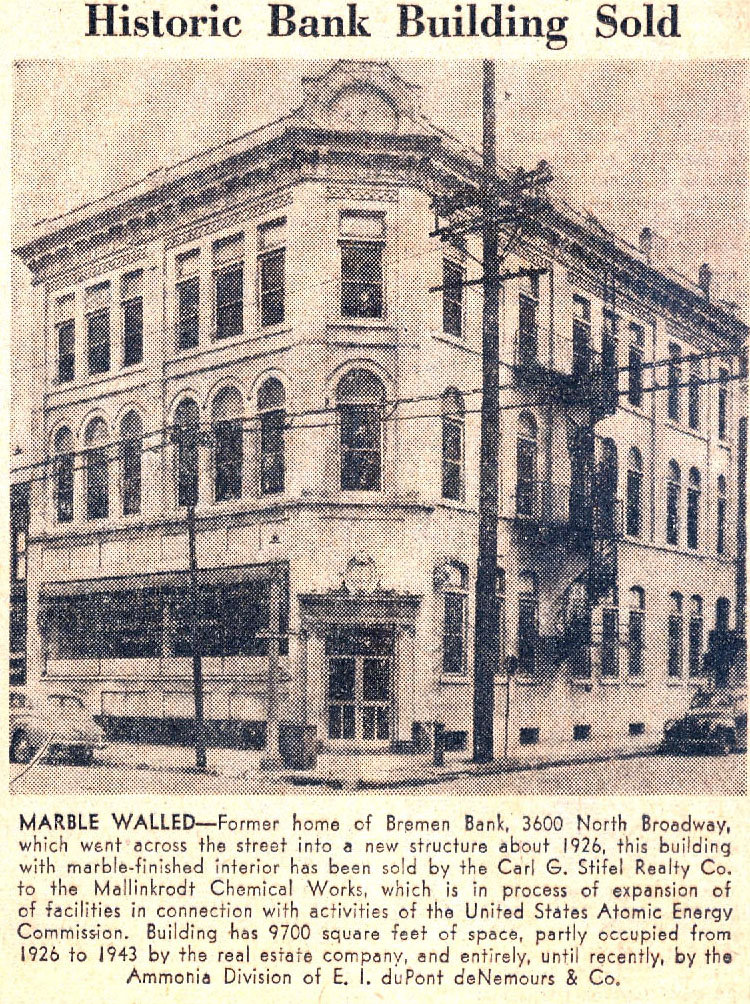

The following scanned clipping comes from the January 9, 1949 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

Some readers know of the 1927 Bremen Bank building diagonally across the intersection of Broadway and Mallinckrodt streets; that lovely historic building remains the home of the Bremen Bank.

Some readers know of the 1927 Bremen Bank building diagonally across the intersection of Broadway and Mallinckrodt streets; that lovely historic building remains the home of the Bremen Bank.

This clipping is interesting because its caption tells the story of what has happened to large buildings built for specific large tenants when the original tenant moves out. First another large user might come along, with a less prominent use of the space (her, a real estate office). Then comes a second wave of office use, and further depreciation of value. Finally, the property is eyed for a larger development. The story here ends a few months after this blurb appeared in the newspaper. After Mallinckrodt purchased the lovely old bank building, it wrecked it. While the blurb mentions federally-subsidized atomic energy activity, Mallinckrodt actually wrecked the Bremen Bank for a worker parking lot. To this day, the site remains vacant save a small building built on the east end if the parcel in 1994.

In 1949, such industrial expansion along Broadway north and south of downtown was not uncommon. Such expansion came on the heels of the 1947 city Comprehensive Plan, which streamlined land uses to industrial in formerly mixed-use areas along the riverfront while calling for a zoning plan that would allow such anti-urban uses as surface parking on a major thoroughfare. Alas, that zoning plan remains in place, while the land use plan finally changed in 2005. Also remaining is the notion that industrial sites need to spread outward, surrounded by parking and open land, and not be more integrated into city neighborhoods. A clipping like this demonstrates that there are formidable constants in historic preservation and urban design. Nearly sixty years later, a lot remains the same.

North Broadway around Bremen Bank, however, does not remain the same. Mallinckrodt’s expansion — much of it for parking — erased most of the pedestrian quality of that street scape. Besides the bank, only a few other small businesses are open there. Interstate 70 forms a barrier between this area and the populated section of the Hyde Park Park neighborhood to the west. The city government officially draws the Old North and Hyde Park boundaries at I-70, further enforcing the separation. Had things progressed differently, the old Bremen Bank could have been retained along with other buildings on Broadway, with Hyde Park connected to its major employer and to the riverfront.

What is puzzling is that at the same time the 1947 Comprehensive Plan’s call for creating an industrial wall along the river was being drafted, civic leaders were also plotting the construction of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial downtown in order to improve the central riverfront. Did no one see the conflict between the policies? There was already an organic urban connection to the river, and it could have been enhanced as the city began its loss of industry. Industrial expansion policies — and, I should point out, the Memorial itself — decimated the street grids, neighborhoods and buildings that bound the city to the Mississippi. The long-term consequences of the old policies are haunting us today. And we don’t have as many resources like the Bremen Bank building around to help reconnect us to the riverfront as we started with.