by Michael R. Allen

Forty years ago today, demolition work started at the conjoined Pruitt and Igoe housing projects. On March 16, 1972, the St. Louis Housing Authority took down half of building A-16 in the Pruitt side of the project through an explosive blast. This was followed by a larger blast that took down all of double-module tower C-15 on April 21, 1972. These two spectacular demolition events led to the ultimate decision to demolish all of Pruitt-Igoe’s remaining 31 towers in 1976 and 1977. Yet on March 16, 1972, the St. Louis Housing Authority was not attempting to kill modernism, high-rise public housing or even Pruitt-Igoe. Instead, the Authority was trying to save these things.

In early 1972, the St. Louis Housing Authority created a task force of local and Department of Housing and Urban Development officials to examine physical interventions that might alleviate the problems at Pruitt-Igoe. The biggest challenge then was vast oversupply of housing units. Fewer than 400 of the over 2,800 units in the 33 towers was occupied. The St. Louis Housing Authority was faced with a need to reduce the unit count and eliminate vacant buildings in order to improve conditions for occupied buildings. Yet the fractional rent collection on the complex made solutions difficult to finance.

The task force elected to explore reducing the towers’ heights to four stories — a somewhat ironic move given that early plans had called for a low-rise development. The 1947 city Comprehensive Plan had advocated low-rise garden apartments on the site, and architect Minoru Yamasaki’s first concept for the project consisted of four and six story buildings. The St. Louis Housing Authority, under the leadership of Director Thomas Costello, elected to experiment with reducing floor heights.

However, recognizing the surplus of buildings and the need for experimentation, Costello successfully sought HUD permission to demolish three buildings in the project. These demolitions would allow for experimentation in demolition techniques to assess value engineering of the floor removal, and they also would allow the Authority to create a park in the center of the project. At one point, the Authority even explored retaining the rubble from the wrecked buildings as a sort of bizarre landscape feature.

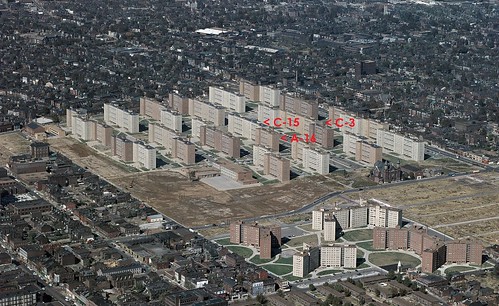

On the morning of March 16, 1972, Costello obtained a building permit for demolition of three towers, to be taken down by explosive blast. The St. Louis Housing Authority selected three towers at the center of the project, along Dickson Street (the only east-west public thoroughfare on the site, and the dividing line between the Pruitt and Igoe projects). The Authority chose towers A-16 and C-15 south of Dickson, and tower C-3 north of Dickson. C-3 would never be demolished by blast. The towers chosen included one of the 180-foot-wide single module towers, A-16, and two 360-foot-wide double module towers, C-3 and C-15. The Authority estimated the cost of demolishing the three towers at $12,000. Over $35 million in bonded construction debt was still owed on Pruitt and Igoe.

The St. Louis Housing Authority hired Dore Wrecking Company of Kawkawlin, Michigan, to conduct the demolition. St. Louis wreckers had never worked with large-scale explosives. Dore Wrecking in turn subcontracted the explosive work to a colorful firm in Towson, Maryland, named Controlled Demolition, Inc. Jack Loizeaux founded Controlled Demolition in 1947, and the company had experience using explosive methods to take down many buildings around Baltimore. The well-publicized Pruitt-Igoe blasts would make the company famous. Controlled Demolition would become the nation’s top firm for explosive demolition, and its future projects would include the Hudson’s Department Store in Detroit, the Kingdome in Seattle, and parts of Yamasaki’s World Trade Center in New York.

For A-16, Controlled Demolition planned to take down only half of the tower by blast. There was electrical equipment in the basement that the St. Louis Housing Authority wished to protect, so the other half would be taken down by crane and wrecking ball. Controlled Demolition placed specially-designed dynamite sticks into holes drilled in the building’s concrete upright columns. The detonation would start at the base of the building, to weaken its support, and travel upward.

On March 16, the demolition event was set for 1:30 p.m. At that time, officials postponed it to 2:15 p.m. That time arrived, and wreckers realized that the blast machine had accidentally went along for a pick-up ride to Lambert International Airport. John D. Loizeaux, president of Controlled Demolition, professed embarrassment at the less than punctual start of demolition. Yet the delays allowed for the blast to start after 3:00 p.m., when Pruitt School sent its elementary students home for the day. The students flocked to the demolition site.

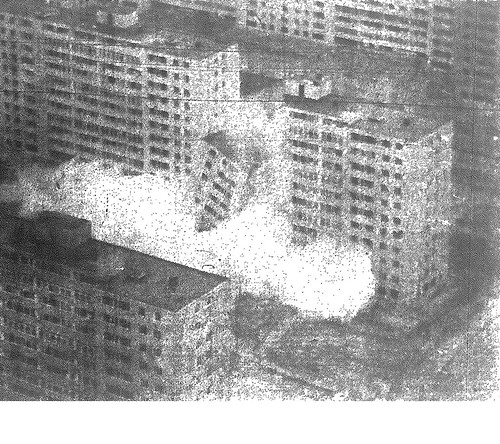

The blasts were heard as muffled gunshot-like sounds, and rather than send out a distress call, they were almost easy to miss. Upon the end of the blasts, the west half of A-16 collapsed in a rising clod of debris. Notable was that the building had lead paint used inside, and there had been no abatement. The slabs pancaked into a pile that would require hand wrecking to remove. Building A-16 was only 17 years old upon demolition, and its reinforced concrete structure was resistant to blast.

At the end of demolition, officials were confident in the methods of Controlled Demolition, and scheduled the second and more spectacular blast for April 21. Yet Thomas Costello told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “[t]his is only the first step, and there are many more to go. We don’t know what they will be at this time.” Pruitt-Igoe was not dead yet.

One reply on “Not the Day Modernism Died, Not Even the Day That Pruitt-Igoe Died”

The Pruitt-Igoe legacy is still killing St. Louis. the whole idea behind Pruitt Igoe is still in place. The City is failing, the proof is the population flees. An urban planning approach that allows for classical city planning principles excludes Le Corbusier and Modernism.

They undermine the idea of the city. Which is where we are at now, the idea of a city is compromised.. Modernist City Planning has failed, what is next? Connecting to the evolution of the classical city is the place to start.

Pruitt=Igoe is a failure on so many levels, it is impossible to delineate. The other question to ask is who the winners were in all phases of the Pruitt Igoe conception to demise? The financial winners may give a clue to motives.