by Michael R. Allen

To some people, the current discussion about McEagle’s “NorthSide” project has roots in a project proposed for the same area 13 years ago: Gateway Village. Like “NorthSide,” Gateway Village involved a close relationship between a mayor and a private developer from outside of the city, proposed massive demolition, proposed eminent domain and large public subsidy. Unlike “NorthSide,” however, Gateway Village never moved close enough to reality to disrupt the section of St. Louis Place it would have wiped out.

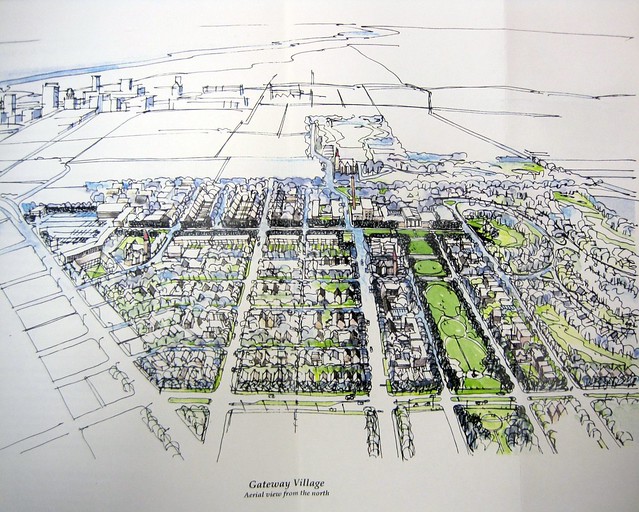

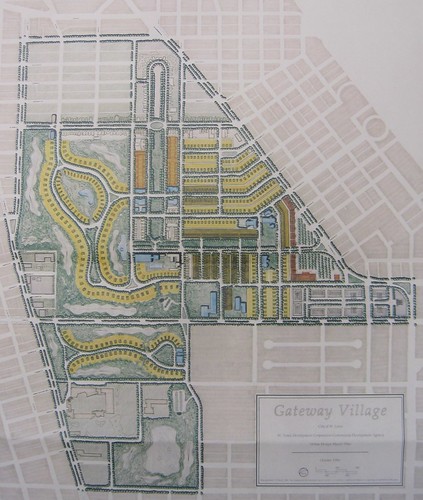

In 1996, Mayor Freeman Bosley, Jr. unveiled his grand plan for revitalizing north St. Louis: a 180-acre golf course and subdivision called Gateway Village that would use the Pruitt-Igoe site as well as the western part of St. Louis Place. The boundaries were Martin Luther King Drive on the south, 20th Street on the east, St. Louis Avenue on the north and Jefferson Avenue on the west. The plan called for building 781 new homes (priced out of range of most St. Louis Place residents) and a 9-hole golf course (designed by renowned designers Don Childs Associates) platted for very low density at odds with surrounding historic city fabric. Going against neighborhood sentiment in an area where he had tremendous political support, Bosley supported the acquisition of 209 residences and six businesses to clear the project site.

The developer behind the project, whose identity was unveiled after the first announcement, was Waycor Corporation of Detroit. Waycor’s president was Don Barden, a wealthy Detroit businessman who has since gone on to become a major casino owner. At the time, Barden was the owner of television stations who had never developed a project on the scale of Gateway Village. Also in 1996, the Federal Election Commission determined that Barden has co-signed an illegal loan to a Detroit Congresswoman.

Whatever his inexperience and lack of ties to St. Louis, Barden gained the confidence of Bosley, Jr. and Maureen McAvey, the director of the St. Louis Development Corporation. Unlike today, where McEagle is unveiling its own plans, in 1996 Bosley and McAvoy did the public relations work for the developer. In August 1996, McAvoy released a study by Don Childs Associates that predicted that Gateway Village would be feasible and successful. The city paid the architects $38,000 for a study that championed a project in which they had a financial interest.

The study predicted that Gateway Village would precipitate “a return to living in major metropolitan cities” and that it would “act as a catalyst to revitalize the area.” The Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association, which is now defunct, rose up against the plan to safeguard the 209 homes sought for condemnation and demolition.

In October 1996, the city government requested a $8 million grant from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development toward the project. The total project budget was $127.5 million, an amount fairly low for such a large area. The low cost was indicative of low density construction and low construction standards. Of course, $8 million was not the only handout sought by Waycor. Waycor wanted an additional $35 million in public financing. Waycor would not commit any of its own capital unless it could secure public money first — also different than the current situation.

The feasibility study commissioned by the city outlined the path toward development, with step one being “complete agreement with Waycor.” That step was removed after the St. Louis Post-Dispatch discovered that the city had commissioned a development feasibility study that not only recommended a certain developer but indicated that an agreement was already being created.

The Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association sent a letter to HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros asking that he deny the $8 million grant request. Shirley Booker was one of the authors of the letter and very active in organizing St. Louis Place residents. Vernon Betts was one of a few St. Louis Place residents who gave favorable comments about Gateway Village to the press, but the majority of residents were opposed.

Bosley’s response to the Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association’s letter is classic and timely: “It’s unfortunate that a small group now want to try and thwart the one thing that can work.” In development, there always seems to be “the one thing that can work” — what the person using that phrase wants to do.

An aldermanic election for the Fifth Ward, where the project was located, came in spring 1997. Veteran Alderwoman Mary Ross was retiring. In the race to succeed Ross, Democratic candidates April Ford-Griffin and Loretta Hall supported Gateway Village, and John Bratkowski was adamantly opposed. Ford-Griffin, whose support was for the project was not staunch, won the seat. At the mayoral level, Bosley lost the Democratic primary to Clarence Harmon.

Even before he took office, Harmon announced his plans to pull city government out of the Gateway Village project. On April 4, 1997, the Post-Dispatch published an article entitled “Harmon: ‘Dead Stop’ for Golf Course Plan,” that covered the mayor-elect’s opposition to a project that would lead to the dislocation of city residents. McAvey retorted that the project would bring the middle class back as well as retail for low-income residents.

Harmon’s move coincided with HUD’s denial of the city’s request for funding. Shirley Booker explained neighborhood opposition well. Residents wanted development, she said, “just not a golf course. We can’t keep existing with all this vacant land. The Lord didn’t mean for it to be like that. It’s a waste.”

McAvey clung to Gateway Village, though, telling the press that no one would be able to develop St. Louis Place without large public subsidy and amenities provided. Her tenure would end shortly thereafter. Ford-Griffin learned a few lessons from Gateway Village and spearheaded an often rocky but productive community-based planning process leading to the Fifth Ward Master Plan, published in 2000 although not fully adopted by the Board of Aldermen.

Harmon, of course, showed little leadership on development issues, but his decision to pull the plug on Gateway Village allowed for the kindling of small-scale development on the near north side. Many leaders, however, continued to bemoan the lack of a large scale plan for the area around Pruitt Igoe. Bosley, Jr. himself is now a backer of the McEagle project, seen occasionally accompanying Paul J. McKee, Jr. at meetings.

One of the problems with the Gateway Village debacle and the resulting Fifth Ward Master Plan is that there was no strong legislative result. The threat of a large-scale plan in the Fifth Ward remained because there were no basic protections against that mode of development. Zoning and land use recommendations were never implemented as law, historic districts and sites were not identified and listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and redevelopment zones that would have broken the ward into smaller pieces were not created. The Fifth Ward’s biggest problem in recent years is the large amount of vacant city-owned land — quite a big prize to lure developers. Without safeguards against large scale projects, the ward has been left vulnerable to the supersized visions that Gateway Village illustrated.