by Michael R. Allen

A version of this article first appeared in the Winter 2009 NewsLetter of the St. Louis Chapter of the Society Architectural Historians.

There is ample recognition of the significance of mid-century motels along roadsides across America, where motels used colorful signage and design to beckon to weary Americans enjoying their automotive freedom. Perhaps because of nostalgic idealization of the motor court and the “open road” and perhaps because of the stigma that postwar urban renewal efforts have attained, local history overlooks the significant wave of urban motel construction that took place in St. Louis between 1958 and 1970.

The 1958 opening of the Bel Air Motel on Lindell Boulevard renewed the building of lodging in the City of St. Louis while introducing a hotel form new to the city, the motel. St. Louis’ last new hotel before that was the nearby Park Plaza Hotel (1930), a soaring, elegant Art Deco tower built on the cusp of the Great Depression. However, another hotel built before the Depression was more indicative of future trends than the Park Plaza. In 1928, Texas developer and automobile travel enthusiast Percy Tyrell opened the Robert E. Lee Hotel at 205 N. 18th Street in downtown St. Louis (listed in the National Register on February 7, 2007), designed by Kansas City architect Alonzo Gentry. While the 14-story Renaissance Revival hotel was stylistically similar to contemporary hotels, it introduced the chain economy hotel to St. Louis.

Tyrell’s Robert E. Lee chain grew to include hotels in San Antonio, Laredo, and Kansas City as well as St. Louis. These were fairly traditional urban hotels in exterior appearance, but not internally. All bearing the same name, the hotels impressed a singular identity upon business travelers in the then-strong St. Louis-Texas trade region. The St. Louis Lee Hotel’s 221 rooms were small but luxurious, and the hotel had but one coffee shop-style restaurant to serve its guests. There were no bars, lounges, ballrooms or other spaces found in large St. Louis hotels up to this time. The Lee simply offered affordable, quality rooms for business travelers who could forgo other frills. The hotel also stood across the street from a major parking garage, making it a convenient stop for the motorist. It survives today as the Railton Residence, a facility of the Salvation Army.

Three years before the Robert E. Lee Hotel opened in St. Louis, the Milestone opened in San Luis Obispo, California. Designed by Los Angeles Architect Arthur S. Heineman, the Milestone sat on a well-traveled road outside of urbanized areas. Rather than consisting of a single building, the Milestone was comprised of several two-room bungalows with attached garages. A restaurant occupied another building. Such developments were usually called motor courts, but Heineman called his a “motel,” shortening the phrase “motor hotel.” The form was replicated many times in the next few years, although the Depression slowed construction and the American tourist industry. Motels or motor courts tended to consist of separate or connected units arranged around a courtyard with a single restaurant or bar serving the guests. The earliest were located exclusively on highways or roads outside of major cities and near major attractions.

As the federal government designated more roads as United States highways and made improvements that encouraged more automobile-based tourism, streets inside of cities began to receive more interstate traffic. In the St. Louis area, motels built before 1957 were located in St. Louis County where there was not yet dense development. The prevalent early motel form was the one-story motor court. This form required large tracts. One of the most famous of the motor courts was the Streamline Moderne Coral Court Motel on Watson Road, built in 1941 and designed by Adolph Struebig. No longer extant except for the façade of one unit displayed at the Museum of Transportation, the Coral Court’s multiple curvilinear clay-tile buildings included attached garages for all units. This feature was common in the motor courts that developed between 1930 and 1960 on Watson Road.

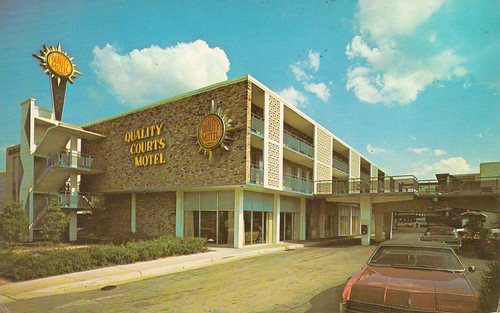

After World War II, developers in cities began building motels of greater density that combined the courtyard form with the density of the urban economy hotels built by Tyrell and others; these tended to be called “motor lodges.” As motel historians Andrew and Jenny Wood write, “Before long, small-time motor courts were rendered obsolete by chains like Holiday Inn that began to blur the distinction between motels and hotels. Single-story structures gave way to double and triple deckers.” Motels sprung up to accommodate the demand for plentiful and affordable lodging. Another shift in the motel industry that followed Tyrell’s lead was the rise of national chains. In 1946, M.K. Guertin founded the Best Western chain and in 1952 Kemmons Wilson founded the Holiday Inn chain; others followed, including the famous Howard Johnson’s. The chains preferred larger buildings in which units were connected and faced shared surface parking. Like the motor courts, the motor lodges of the 1950s and 1960s required large lots and were constructed mostly on the periphery of the city. The motels are epitomized by a Howard Johnson built on Lindbergh Boulevard in suburban south county built in 1957: 40 units in three one-story buildings surrounding a separate restaurant building, with an overall low density.

In the City of St. Louis, the Bel Air introduced the motel form, starting a building boom that lasted through 1970. St. Louis County already had several motor courts and lodges, especially along Watson Road, which was part of Route 66. The 1959 Polk’s City Directory shows only one listing within the city limits under “Motels and Auto Courts” — the Bel Air. By 1971, 16 were listed. Most had been built after 1962. Six were located downtown, four in the Central West End, one in Midtown, one in south city, one west of the Central West End, and three in north city. Most had 100 rooms or more, but one was as small as 22 rooms. Six were owned and operated by national chains. Almost all were designed in the styles of the Modern Movement.

The Bel Air Motel

In 1957, developer and philanthropist Norman K. Probstein announced plans for the 150-room Bel Air Motel at 4630 Lindell Boulevard in the Central West End. Obscure architect Wilburn McCormack came up with a design that fit within the general realm of the International Style: a grid formed by the white-painted concrete of the structure, large windows, metal panels, red brick. A three-story section in the rear sat atop a covered parking garage. A T-shaped two story section formed a courtyard with swimming pool (a make-or-break feature for a modern motel). The front elevation was essentially a glass box, and extremely different than anything that had been built in the Central West End up to that time. No large hotel of any kind had been built in the city since the Park Plaza Hotel.

However, the Bel Air was most notable for setting the new conventions of “luxury” (Probstein’s own word) lodging in the city. While the motel defied the conventions that had typified pre-Depression hotels, the image of luxury was retained. The Bel Air’s advertising makes clear it was not a “budget lodge” but a sleek urban motel for the traveling businessperson. Inside of the Bel Air was a spacious modern restaurant, as well as an exotic cocktail lounge. The rooms had large windows, desks and balconies. The swimming pool provided recreation, and the 175 covered parking spaces offered privacy and safety. All of these ingredients would resurface with the larger motels in the city.

The Bel Air would hold its place among the motels built after its opening due to its configuration as a luxury motor hotel. A 1961 St. Louis Globe-Democrat article entitled “Building Boom in Motor Hotels” lays out the characteristics of local “luxury” motels: good furniture in the rooms, real art and antiques in lobby, a heated pool, a full-service restaurant and bar, meeting and conference rooms, king size beds and fridge in all pools. The restaurants might have a South Pacific or Polyneisan theme, like Trader Vic’s at the Bel Air East. The Bel Air provided all of these, true to Probstein’s vision. The article mentions the DeVille as its only city example, but the Bel Air and Bel Air East were certainly its predecessors as high-end motels marketed to businessmen rather than casual tourists. The Bel Air was so immediately successful that he added a third floor to the front section one year later (designed by Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen). The total room count became 198.

The Diplomat, the DeVille and Building Code Changes

Immediately following the Bel Air came the Diplomat at 433 N. Kingshighway at Waterman (now the site of Central Reform Congregation’s synagogue). The building permit dates to September 16, 1959, with Hausner & Macsnai of Chicago as architects in consultation with Joseph R. Passoneau, then dean of Washington University School of Architecture. The 180-room, three-story Modern motel occupied the site of the 75-room Usona Hotel, dating to 1902 and demolished for the project. Adolph Rosenberg headed a group of investors that purchased the site and built the new motel. The Diplomat, located a few blocks northwest of the Bel Air, demonstrates not only the immediate influence of the new motel but also the demand for lodging in the Central West End that had begun in the 1920s. As Clayton lured more businesses out of downtown, the Central West End became a convenient middle point for business travelers.

In 1961, the DeVille chain based in New Orleans entered the St. Louis market in close proximity to the successful Bel Air. Developer Paul Kapelow purchased a large site at the northeast corner of Taylor and Lindell avenues, where three large houses stood. These houses had been damaged in the 1959 tornado, and Probstein had considered the site for a second motel that same year.

Opening in 1963 at 4483 Lindell Boulevard, the striking, E-shaped DeVille Motor Hotel rose to 11 stories in its center section. The DeVille boasted 226 rooms and 180 parking spaces as well as a swimming pool. Of all the motels built after the Bel Air, the DeVille was the most unusual architecturally. Its curvilinear concrete forms were the sophisticated design work of Charles Colbert, a renowned New Orleans architect and modernist who would later serve as Dean of the Columbia University School of Architecture.

Yet the mass, site and style were not the only features noted in the press. When the builders broke ground in October 1961, they were making local building history. The new DeVille Motor Hotel would be the first major building built after the city’s adoption of a new building code earlier that year. This code more than anything enabled builders of economy motels to seriously consider locating within the city limits.

Prior to the 1961 building code, large buildings were restrained by requirements that the majority of wall surface area meet a defined thickness. Materials like concrete panels and glass had to be employed within larger wall systems, and could not be used to clad an entire building. Before 1961, construction of a glass high-rise in St. Louis was not permitted by code. The removal of the old restrictions allowed St. Louis to embrace the building technologies that allowed for fully modern architectural expression.

Mayor Raymond Tucker was an enthusiast for the DeVille project. In a St. Louis Post-Dispatch article from 1961, the mayor raved: “Certainly, this will be an impressive monument to the perseverance of those far-sighted citizens who worked on our code for more than five years.” Greater modern expressions would rise in St. Louis, of course, but the DeVille was the first to fully embrace the code. Gone was the need to use solid masonry, as the Bel Air and Diplomat motels did. Costs could be lower and — realized at least in the case of the DeVille — the architect’s hand could be unfettered.

More Motels: Parkway House, Ebony, Carousel, Warwick, Lennox, Ben Franklin

Another Central West End motel was the Parkway House (now razed and replaced by the Metro Lofts), located at 4545 Forest Park Parkway and completed in 1963. The building permit dates to August 13, 1962 and inexplicably refers to the 119-room motel as an apartment building. The cost was $795,000 and California architect J. Richard Shelley designed the four-story building. Architecturally, the Parkway House was a departure from its contemporaries. The rooms were arranged around two courtyards shielded from external view, save for one cut-through. The room entrances were on the perimeter, where long open corridors with concrete knee walls were interspersed on the front elevation with large glass walls at stairwells. The courtyards featured brick walls and the private faces of the rooms, which had balconies.

An unsigned Post-Dispatch article from around the motel’s opening celebrated Parkway House’s design and hinted that the conventions of motel design had been noted by the reporter: “Projected [on Parkway House] was the idea that motor hotels don’t have to be all of the same hum-drum pattern and that this could be different.”

Hum-drum or not, there was definitely a pattern building in city motel construction. In the next nine years, other developers would adapt the motel to various sites in the city from large downtown lots to sites in commercial districts in north city. The 22-room Ebony at 3622 Page (1963) and the 60-room Carousel at 3930 N. Kingshighway were small one-story motor courts in north St. Louis. The Warwick Hotel at 15th and Locust downtown built an adjacent 3-story, 58-room motel in 1964, while the Lennox (built in 1929) at 823 Washington downtown attempted to rebrand itself as the Ben Franklin Motor Hotel with the addition of a parking garage in 1965.

The Bel Air East and the Downtowner

In the 1960s, two multi-story motels larger than 150 rooms with budgets over $1 million were built downtown. The 9-story, 203-room Downtowner at 1133 Washington adapted to a rare large vacant lot in a high-density location. Building permits issued on November 23, 1962 and March 21, 1963 report a total construction cost of $1.7 million — a small figure compared to the DeVille’s $4.5 million cost. Designed by Memphis firm George Thomason and Associates, the Downtowner occupied the site once occupied by the Carleton Building and cleared in 1928 by Chicago railroad magnate Samuel Insull. Insull, owner of the Illinois Traction System whose electric interurban line terminated at the site. Insull’s grand plans for a skyscraper at Tucker and Washington never came to fruition, although his company completed the Central Terminal Building to the north in 1932. The Downtowner site had been left open to the tracks below for 36 years before construction.

Guests to the Downtowner could pull their cars in off of Washington, where a courtyard opened into the motel lobby. The building formed an L-shape, with the courtyard opening extending upward to offer additional light to the rooms. On the first floor, the motel offered a corner restaurant and a smaller cafe. A modest ballroom and two meeting rooms were provided. The Downtowner building certainly capitalized on the new building code. The concrete structure’s floor plates extended through the walls, with only glass and metal serving as a thin curtain wall on each story. The walls of each room were beveled in pairs to provide an accordian-like appearance. At the corner of the building where there was a stairwell, the wall was clad in a grid of alternating colored metal panels. As with many mid-rise buildings of the era, including the Plaza Square Apartments, color was employed as an element of articulating what otherwise may have been a monotonous expanse of lines. After the Best Western chain took over, it eventually painted over the colored panels. By the late 1990s, the panels were a dull and often-maligned brown. Thomasan’s design proved more economical than imaginative. In 2008, the building was rehabilitated as apartments and the exterior nearly completely reclad in granite and modern metal.

After the Downtowner came the 15-story Bel Air East in 1963. The 192-room hotel cost over $3 million to build, and its design program reflected a high budget. As with the first Bel Air, Probstein aimed to distinguish the motel by making it luxurious. A 1962 Post-Dispatch article on downtown development wrote about the motel’s features, including its 300 enclosed parking spaces, the Popover Room restaurant (serving pancakes and charcoal cooking) and rooms with views of the Mississippi River and the future Gateway Arch. The article notes: “Some of the enticements of the main deck of a luxury liner will be incorporated into the fifth floor terrace†including a heated pool, shuffle board, children’s playground and illuminated putting green.”

Architects Hausner & Macsai of Chicago, designers of St. Louis’ earlier Diplomat Motel, gave the Bel Air East a vertical emphasis. The base of the building was a four-story podium, with a recessed first floor under three levels of parking. A stylized concrete grille shielded the parking floors, and an exaggerated Polynesian entrance on Washington Avenue led to Trader Vic’s bar. Above the podium were gardens and a swimming pool flanking the central tower, which presented blind dark brick walls to the east and west. The north and south sides were framed in a concrete grid. The grid outlined balconies behind which were the recessed glass walls of the rooms. Again, saturated colors were used to add stylistic complexity and whimsy. Here, the architects had the curtains within each bay of the tower in alternative colors, so that there were vertical color stripes along the sides.

Not only was the design of the Bel Air East more sophisticated than some of its predecessors, but its designers had a much more significant body of work. Hausner & Macsai was a partnership between Hungarian-born John Macsai (FAIA) and Robert Hausner that lasted between 1955 and 1970. Among the firm’s work are numerous high-rise apartment buildings in Chicago, including several on Lake Shore Drive. A contemporary work to the Bel Air East, is the firm’s apartment building at 21 East Chestnut Street in Chicago. That building shows a distinct similarity to the St. Louis motel in the exterior expression of the concrete structural grid. Macsai remained a prominent Chicago architect well into the 1990s.

Construction of large motels in the early 1960s attracted local press attention. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch‘s popular weekend “Pictures” feature for November 24, 1963, featured photographs of the Downtowner, Bel Air East and DeVille. Writer Clarence Olson was bullish on the new hotels: “St. Louis, for the first time since the 1920s, is having a hotel building boom. Too sumptuous to be classified as motels, they combine the features of a major downtown hotel complex with the convenience of a highway hotel.” Olson noted the 1961 building code as “major factor” in the boom.

According to Olson, the travelers were mostly “businessmen traveling on expense accounts and attending conferences” These travelers on the move were much like the patrons of the Robert E. Lee Hotel back in the day, but were accustomed to the luxuries introduced by Norman Probstein at the Bel Air.

An unbuilt downtown project from the late 1960s would have offered an unprecedented strange twist on the motel. In 1968, developer Charles Cherry received a mooring permit for the “Bo-Tel,” a floating motel clad in gold glass to be located on the Mississippi River centered on the Gateway Arch. The convenience of arriving by car would be joined to the convenience of arriving by boat or even private helicopter! Cherry’s 420-foot long, 5-deck structure would have had its own floating swimming pool and marina in addition to a more conventional motel load of 240 rooms, a private club, three cocktail lounges and two restaurants. Cost was estimated at $7.2 million, and the despite announcements of construction, work never began.

Another Modern downtown hotel was Stouffer’s Riverfront Inn (1969) at 200 S. Fourth Street, with its central the circular tower. However, Stouffer’s was built in the manner of previous downtown hotels, with large convention, meeting and ballroom spaces, several restaurants and shops and without interconnected parking. While having a site similar to motels, with a large front lawn and wide entrance driveway, Stouffer’s Riverfront Inn (now the Millennium Hotel) has always been a hotel, not a motel. Construction of Stouffer’s would mark the return of constructing new full-service hotels to serve downtown visitors and conventioneers.

The End of the Boom

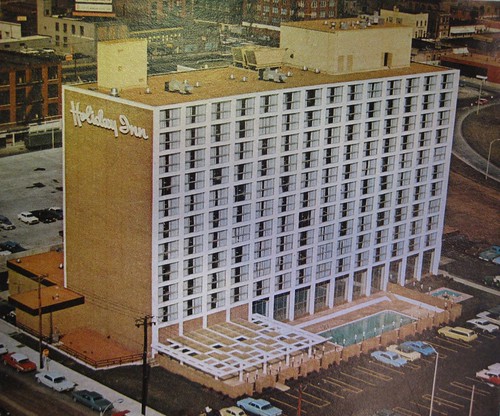

Many of the new motels in the central city were built on sites cleared for urban renewal, including the 11-story, 250-room Holiday Inn Downtown at 2211 Market Street and the 103-room 2-story Travelodge at 3420 Lindell, both built in 1964 in the Mill Creek Valley area. The largest motel built outside of the central corridor was the five-story, 103-room Congress (1964), designed by William B. Ittner, Jr. and Lester C. Haeckel and located at 6543 Chippewa on the city leg of Route 66. The last of the motels built in the city during this period was the striking cylindrical high-rise Rodeway at 2600 Market Street downtown, built in 1970 and expanded in 1973.

Of these motels, those with reported construction budgets over $1 million included the tallest: the DeVille, the Downtowner and the Holiday Inn Downtown. Most were built rather economically, of widely-available materials like brick, aluminum, concrete and glass. Many of the architects responsible for these designs are not well-known, and many are from cities outside of St. Louis due to the chain connections of the motels. Charles Colbert is the exception, not the rule, to the architectural pedigree of the motels. By and large, the greater motel designs from the postwar period were found in St. Louis County, including Meyer Loomstein’s Colony Motel (1965) in Clayton.

Today, of the 16 motels listed in the 1971 city directory, six remain standing. When the Bel Air re-opened as the Hotel Indigo in 2009, it joined the Bel Air East, Carousel and Ebony as the only ones still operating as motels. Most of the motel buildings have been altered to states that do not resemble their historic appearance: the Bel Air East and the Downtowner have been completely re-clad; the Holiday Inn Downtown has had a new pitched roof placed over its flat roof; the Carousel and Ebony have had numerous alterations to window opening size; the Congress was retrofitted for senior housing with major room configuration changes as well as a prominent elevator shaft addition built in 2008. The only remaining motel from the city’s peak years of construction that still retains sufficient architectural integrity to be eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places is the first Bel Air, listed in 2009.

The few motels constructed in the city since the Rodeway have been low-rise buildings of little architectural merit. The rise and fall of the motel in the city limits may not have been as illustrious as it was in other parts of the country, but it marked a significant return to new lodging construction and design in St. Louis. The impermanence of the physical traces of this period demonstrates not only the short-term vision of motel developers but also the uneven match between this automobile-based form and an urban city. Fifty years after the arrival of the motel in the city, planners wisely have turned away from the idea of outright embrace of the automobile. Postwar architecture is often threatened by new construction of higher density. The remaining motels of the city, in whatever degree of integrity, give testament to a recent and relatively brief intersection of a new American building type and an old city.

Bibliography

“$4,500,000 Hotel to Be Built at Corner of Lindell, Taylorâ€, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 30 September 30, 1961.

Allen, Michael R. National Register of Historic Places Inventory Form: Robert E. Lee Hotel. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, 2007.

Baxter, Karen Bode et al. National Register of Historic Places Inventory Form: Bel Air Motel. Washington, D.C.: Department of the Interior, 2009.

Delugach, Al. “The New Face of Downtown St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 17 June 1962.

Derrington, Lindsey. “Recoup DeVille Motor Hotel: No need to demolish historic building,” The Vital Voice, 23 April 2008.

“The Downtowner to Open This Week, ” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 9 August 1964.

Goodman, Rachel Anne. “The Very First Motel.” 2004. http://savvytraveler.publicradio.org/show/features/2000/20000728/motel.shtml, Accessed 9 October 2008.

“Johnson Motor Lodge’s Opening Here Tomorrow,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 16 June 1957.

Liebs, Chester. Main Street to Miracle Mile: American Roadside Architecture. Boston: Little, Brown, 1985.

Macsai, John. Interview, Chicago Architects Oral History Project.

Olson, Clarence. “Pictures,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 21 November 1963.

“The Parkway House, “St. Louis Post-Dispatch, 22 September 1963.

Polk’s City Directory, 1958-1971.

Sanborn Fire Insurance Map: 1964.

St. Louis Daily Record.

St. Louis Hotels, Taverns, Restaurants, Vol. I. 7. St. Louis, Missouri: Collection of the Missouri Historical Society.

Wood, Andrew and Jenny Wood, Motel Americana. http://www.motelamericana.com, Accessed 9 October 2008.

2 replies on “Motels in the City of St. Louis”

[…] Skip to content HomeAboutEcology of AbsenceWho We AreAppearancesArchitectural ToursConsulting ServicesPlacesIndex of BuildingsIndex of PlacesProjectsResourcesMap ResourcesResearch Your HomeSt. Louis City LandmarksContact ← Motels in the City of St. Louis […]

This is such a neat article. I love learning more about the past of my hometown, St. Louis. Love seeiing what it used to look like and the old buildings! Thank you!