by Michael R. Allen

This is the second part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

Landscape architect George Kessler was one of the chief theorists of rationalist urban planning. Kessler designed the 1904 World’s Fair landscape, which was a masterpiece of orderly expansive views. Kessler had little use for formal gardens or wildness; he favored large neat orderly lawns defined by imposing trees or dramatized by the placement of ornate buildings. Rather than emphasize the delights of natural flora, Kessler underscored the beauty of a total landscape. At the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904, this landscape included ornate Beaux Arts buildings. Here was a mirror of the early ideal of the Gateway Mall — orderly formal landscape contained by monumental public buildings. Mayor Rolla Wells was a supporter of Kessler and put him to work on several urban planning projects, including a plan for Kingshighway that envisioned the road as a true parkway.

In the absence of an official city government planning apparatus, the reform-minded Civic League created a City Plan Committees to undertake the first comprehensive city plan in 1905. The Plan Committees included numerous prominent businessmen, political leaders, architects and engineers. The Committee published the city’s first Comprehensive Plan in 1907. The Committee reported that there was one acre of park for every 96 people living west of Grand and one acre for every 1,871 between Grand and the river. The Committee found this density undesirable and recommended creating additional park space through clearance. One-hundred years later, after decades of demolition in the central core of our city has destroyed entire neighborhoods and rendered others dysfunctional, the Committee’s plan seems short-sighted. The difference recorded in the number of park acres east and west of Grand did not necessarily indicate any real difference in quality of life. It simply recorded a greater building density east of Grand in the oldest walking neighborhoods of the city. Later city planners would to appreciate the boost high building density gives to fostering strong community ties, creating safe streets, creating vital commercial districts, and raising property values.

The rational age of city planning was hitting its stride in 1907, however. The rationalist national movement known as “City Beautiful” was highly influential in St. Louis due to the advocacy of Kessler for its principles. Kessler served on the Inner and Outer Park Committee of the Civic League, and his associate Henry Wright served on the Civic Centers Committee. Together they worked to ensure their philosophy was articulated in the city’s first comprehensive plan. The Comprehensive Plan included an entire chapter on “A Public Buildings Group” that quoted in full the earlier recommendation of the Public Buildings Commission of 1904 for a similar plan. That commission consisted of architects John Mauran (chairman), William S. Eames (secretary) and Albert Groves, all staunch believers in City Beautiful ideals but not as forcefully visionary as Kessler.

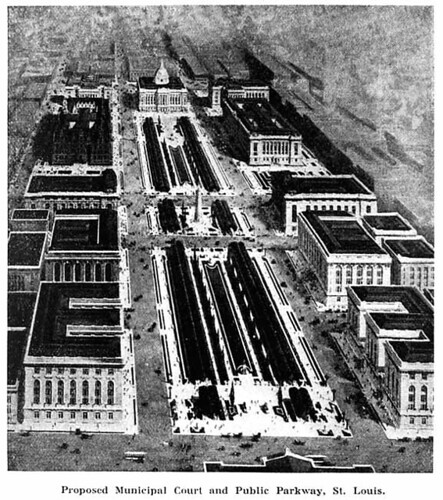

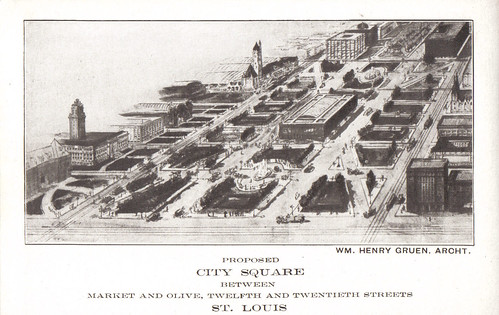

Still, Kessler and the Civic League resurrected the words offered quite recently along with carefully-selected illustrations of the Place Vendome, Trafalgar Square and the Zwingerhoff to seduce elected officials into accepting the City Beautiful vision and contrast with the reality of a crowded western downtown. The Civic League recommended alleviating downtown’s overcrowding by clearing several blocks of buildings between 13th and 14th streets from Clark north to Olive streets for a new park mall. Surrounding the mall would be grand public buildings, rendered in splendid Beaux Arts formalism in the illustrations accompanying the plan. City Hall, which had been completed in 1896 on most of Washington Park, would be joined with new courthouses and a new central public library. “Under no circumstances should this opportunity of establishing a focal center for public edifices be permitted to pass,” concluded the plan — and its words would be heeded.

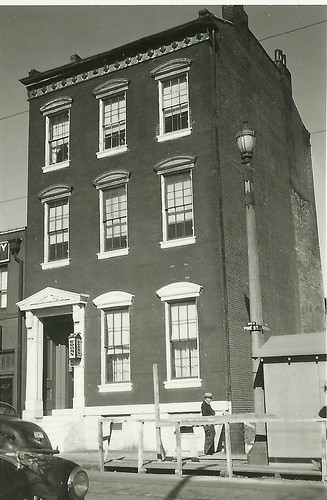

The area of downtown recommended for clearance was widely known as a notorious red-light district and African-American slum. According to historian James Wunsch, prostitutes began settling on Chestnut, Market and Pine streets between 12th and 15th street as early as the mid-1880s. The area also had been included in a zone that police had tried to clear of prostitution between December 1894 and March 1895. That sweep was unsuccessful, although it pushed some brothels west on Market Street. These streets were at a unique confluence between the rail yards and surrounding industrial and low-rent residential areas of Mill Creek Valley to the south and the fading elegance of Lucas Place to the north. Because of City Hall’s location at 12th and Market, the area was especially problematic to the city’s image. By 1907, the north side of Market Street was a blemish seen by anyone who emerged from Union Station or City Hall, the two most important downtown public buildings. The 1907 plan addressed the immediate need to both create a civic center and eradicate the blight around City Hall. The problems to the west would be the subject of subsequent plans.

The contrast between the existing environment and the proposed replacement was equally obvious. Gone would be the patchwork of old brick buildings with the mix of tenement apartments, shops, corner storefronts, and warehouses. Instead, the blocks would be a sweeping green space with minimal disruption. Surrounding the park would be a controlled monolithic use. The plan called for nothing short of complete conquest and control of these city blocks; park space was antidote to both social and architectural ills. The 1907 plan did not result in a rush to implementation, but the idea of a civic plaza gradually snowballed as it rolled through subsequent city planning documents.

One reply on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 2): The Civic Center”

The cursive hotel sign in the photograph above is absolutely fantastic!