by Michael R. Allen

This is the ninth and final part of a series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

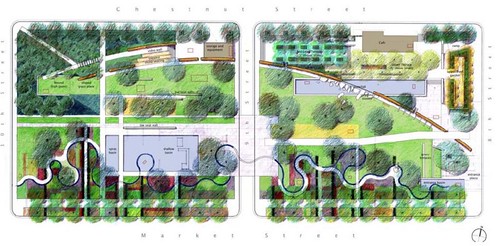

The 2007 Gateway Mall master plan provided impetus to the development of the two blocks of the mall between Eighth and Tenth streets as the successful Citygarden. Designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz architects and completed in 2009, Citygarden is an interactive sculpture garden that has garnered favorable criticism from the New York Times. Citygarden’s two blocks share the “hallway,†a wide formal tree-lined sidewalk along Market Street recommended by the new Gateway Mall Master Plan. However, the blocks eschew further strict formalism. Linear paths follow the somewhat irregular lines of long-abandoned alleys, while a gentle arc runs through both blocks. The north sides are raised up, with the eastern block containing a waterfall and minimalist cafe building on its high side and the western block rising up to a whimsical forested hill atop which is placed a sculpture. There is a plaza on the western block alive with fountain jets adjacent to a grid of large metal pedals upon one which one can jump to trigger bells at different tones. All of the sculptures can be touched. Citygarden has been so successful that the section of 10th Street between the two blocks remains closed to shield the heavy pedestrian traffic.

Citygarden’s design discarded rationalist notions of open space and view in favor of a contemporary landscape design theories of the need for activation, asymmetry, whimsy and native plantings. The small size of the intervention — two blocks — creates clear boundaries and edges of Citygarden that drive pedestrians into its space. The success of Citygarden in part comes from employing long-standing observations about the utility of basic urban design features that encourage circulation and building density.

In his 1938 volume The Art of Building Cities, Camillo Sitte discusses the great public spaces of historic European cities. According to Sitte, the plan of a successful urban park must be irregular and enclosed with the size no larger than 465 ft by 190 ft. The park width should be equal to the height of the principal adjacent building, while the length should be no more than twice this dimension. Statues or monuments should be located on the periphery to maximize circulation of people within the park. Sitte stated that the park need not have plants or lawns. Unsurprising, Sitte’s ideas of sensitive central city park space germinated slowly in the United States.

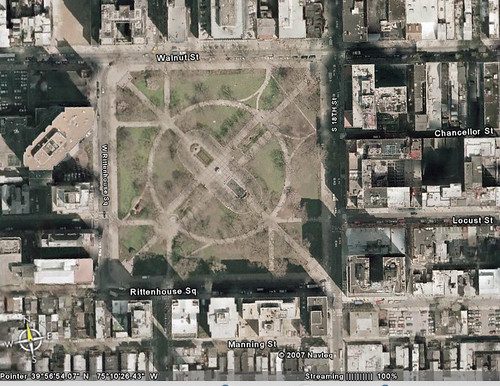

In her classic 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs compared four public parks within a roughly equal distance of Philadelphia City Hall in the center city. Jacobs found high usage at only one of the four parks, Rittenhouse Square. The reason for its success, according to Jacobs, lay in its surroundings. Rittenhouse Square is surrounded by mixed uses that generate constant foot traffic. The square is a crossing amid a dense urban environment, and proximate to ground-floor activity in surrounding buildings. In short, Rittenhouse Square has the clear and purposeful boundaries and the surrounding human density to be simultaneously well-defined and well-used. Again, Tom Turner summarizes the situation well with the statement: “Success depends on the exact character of the bounding membrane [of a park].”

After conducting a study of public spaces in New York City in 1980, critic William H. Whyte concluded that “what attracts people most … is other people.” We can construct dazzling follies and plant beautiful gardens on the Mall, but without circulation it will never amount to a decent public space. And it will not generate circulation if its surroundings remain hostile to pedestrian life. Indeed, people do seek other people — at restaurants, at gallery openings, at night clubs and in residential and office buildings. These things are in short supply on Market and Chestnut streets, beyond the few retail spaces north of Kiener Plaza. Citygarden is such a singular park space that it drives its own demand for use, which in turn has boosted pedestrian traffic around it. A converse positive relationship between park and activity of Citygarden also can be seen in a smaller, earlier downtown park.

Strangely, a downtown park that enjoys much casual use throughout warmer months is one facing the mall on Market Street in front of one of the office buildings built in the 1980s. The plaza in front of 1010 Market Street, at the southeast corner of Market and 11th streets, was designed by architect Edward Larrabee Barnes as part of the building design. The building itself, with its white grid around window ribbons, is a post-modern reincarnation of International Style minimalism. The plaza uses well-defined design elements: a grid of pathways with trees planted in the squares created by the paths. There are a few benches, a lot of shade and defining enclosure provided by building walls. The glass wall exposes a lobby and restaurant space to this plaza, employing visual continuity between interior and exterior common to Modernist-inspired work. This little park is simple, well-designed, comfortable and placed adjacent to traffic-generating use.

The qualities that make Barnes’ park space functional eluded many of his contemporaries, but they are apparent in the popular Citygarden. Over one hundred years since publication of A City Plan for St. Louis, the Gateway Mall reflects a tortuous implementation and constant boundary changes. However, the quality of design found in Citygarden shows that the flaws of the ideas applied to the mall in the past are not permanent impediments. The Gateway Mall will continue to change as the current Master Plan is implemented, and will lose much of its monumental formalism. Within the next decades, the Gateway Mall will become the embodiment of early 21st century park planning principles. Today’s architects and planners follow many others’ foot steps in trying to envision the string of city blocks between Chestnut and Market as useful, important urban park space. While contemporary park planning embraces many of the theories that criticized previous ideas from the City Beautiful movement, its practitioners are laboring under contemporary economic and ideological circumstances. In some ways, the Gateway Mall is still being shaped according to current landscape design trends rather than as part of a broader planning strategy for downtown. Whether the mall itself gains an identity in the next decade depends on the quality and scope of interventions to come.

Cumulative Bibliography

Abbott, Mark. “A Document That Changed America: The 1907 A City Plan for St. Louis.” St. Louis Plans: The Ideal and the Real. Mark Tranel, ed. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 2007.

City Plan Commission. St. Louis Central Traffic-Parkway. St. Louis: City Plan Commission, 1912.

—. A Plan for Downtown St. Louis. St. Louis: City Plan Commission, 1960.

City Plan Commission and Harland Bartholomew. A Public Building Group Plan for St. Louis. St. Louis: Nixon-Jones Printing Company, 1919.

Civic League of St. Louis. A City Plan for St. Louis. St. Louis: The Civic League, 1907.

Gateway Mall Redevelopment Corporation. A Plan for Development of the Gateway Mall. St. Louis: Gateway Mall Redevelopment Corporation, 1982.

Giles, L.W. The St. Louis Gateway Mall Scrapbook. St. Louis: St. Louis Architectural Art Company, 1998.

Jacobs, Jane. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House, 1961.

Market Preservation Archive. St. Louis, Missouri: Library of the St. Louis Building Arts Foundation.

Planning and Urban Design Agency. St. Louis Gateway Mall Master Plan. St. Louis: Gateway Mall Project, 2007.

Robinson, Jack. “The Battle for the Gateway Mall.” St. Louis (December 1982).

Sandweiss, Eric. Evolution of an American Urban Landscape. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001.

Sitte, Camille. The Art of Building Cities. New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1945.

Toft, Carolyn H. and Michael R. Allen. National Register of Historic Places Inventory Form: Plaza Square Apartments Historic District. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, 2007.

Turner, Tom. City as Landscape: A Post-Modern View of Design and Planning. London: E & FN Spon, 1996.

Whyte, William H. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Project for Public Spaces, 2001.

Wunsch, James. “Protecting St. Louis Neighborhoods from the Encroachment of Brothels, 1870-1920.” Missouri Historical Review 104.4 (July 2010).

2 replies on “The Evolution of the Gateway Mall (Part 9): Great Public Space Ahead?”

I’m not convinced that most of the buildings facing the Gateway Mall have urban values. This is not to say the architecture might not have merit, although a big part of an individual buildings value is determined on how it relates to its surroundings.

I don’t know if any of the recently built structures along the Gateway Mall contributes in a meaningful way.

An interesting line of thought would be see how many visitors to the Citygarden would have arrived in ways other than the auto. Probably not many.

I think the lack of a major transit station in the Mall weakens it, as does the lack of adjacent commercial. Of course there is shape and density also. Look at the above sample of Rittenhouse Square and how the adjacent buildings crowd around to form the public space. (I agree with your Tom Turner quote above, although the defects go beyond the bounding membrane.)

A look at transit around Rittenhouse will probably show a robust transit that serves the surrounding density that is a element of the bonding membrane).

The adjacent buildings along the Gateway Mall do little to contribute to the social life that is needed to enliven the city; nor do they collectively shape the space along the Gateway Mall.

1010 Market may be a starting point, I don’t know, but that is real problem, the city doesn’t know either.

Classical interactions of urban space, proven over centuries, are ignored.

Â

Oh, who cares about Philadelphia! or Edward Larrabee Barnes? Â Not me. Â You shouldn’t either. Â

City Garden is an original urban design concept. Â Original. Â There are no other examples of intimate sculpture gardens in urban settings. Â Anywhere. Â

Those two blocks form a brilliant urban gesture.  Better yet, that masterful innovation was  implemented by genuine urban renegades.  Living here among us.

It’s the biggest, but CG is just one of a dozen sublime urban gestures made by those same renegades. CG one of the most fantastic pieces of new urban theory ever. Â

Clearly, they don’t expect the US Calvary to save the urban fabric of St Louis.

That’s the big urban design story about CG and Gateway Mall.