by Michael R. Allen

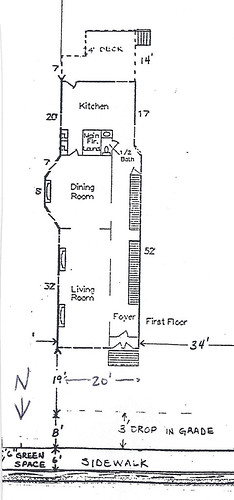

The William Cuthbert Jones House, located at 3724 Olive Street, is a rare example of a 19th century town house that not only survived the decline of Midtown but has also retained substantially its historic character with few alterations. The limestone-faced two-story brick house in the Italianate style was designed by architect Jerome Bibb Legg in 1886 for William Cuthbert Jones, a prominent attorney and criminal court judge.

The house is a good representative example of both Legg’s many client-driven house designs and of the sort of residences that were built on Olive Street in the 1880s. Compared to larger houses on more prominent streets in the Midtown neighborhood, houses on Olive were relatively smaller and less ornate. The house is also noteworthy as one of a handful of extant local works by Legg, who took on much work elsewhere.

Setting and Architecture

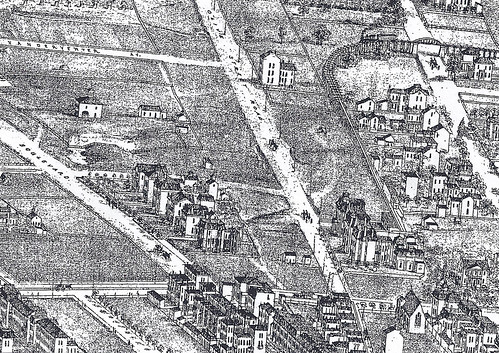

Development of the city west of Grand Boulevard in the Midtown area was spurred by two events in the 1860s: the death of landowner Peter Lindell in 1861, followed by the subdivision of his estate, and the opening of a streetcar line on Olive Street west to Grand by the Missouri Railroad Company in 1864. In 1867, the Lindell Railway Company followed suit and opened its own streetcar line on Washington that extended as far west as Vandeventer Avenue. By 1875, families were living west of Grand and major streets like Lindell Boulevard were laid out (see illustration). Residential development boomed in Midtown between 1875 and 1900. West Pine, Lindell and Grandel (then Delmar) streets emerged as the preferred streets for mansions and wealthy residents, while other streets like Olive, Laclede and Westminster “contained comfortable homes, built on a smaller scale” as historian Jean Fahey Eberle writes. Olive Street was not really a contender for more lavish residences due to the presence of the noisy streetcar line and the West End Narrow Gauge Railroad, which opened in 1878 and ran on the alley north of Olive from a station near Grand Avenue. Thus, the houses built on Olive tended to be more modest homes for businessmen, politicians, doctors and others of some wealth but by no means upper-class. Still, the character of the neighborhood was genteel; the distinctions between the quality of streets was somewhat relative.

The William Cuthbert Jones Home was one of the first houses built on a tract of land, known as the Pettus and Hardy Addition, that was subdivided around 1885. The 1883 Hopkins Fire Insurance Map shows that the present-day Spring Avenue was not even laid out and no buildings yet built on the south side of Olive. Some of this land was owned by the Covenant Mutual Life Insurance Company, which was hesitant to subdivide. In fact, there are three deeds between 1884 and 1886 conveying the land at 3724 Olive to Jones; the subdivision was apparently postponed until 1886, when Jones took out a building permit for a house costing $5,500 to build and designed by architect Jerome Bibb Legg. Most other houses and flats, including other buildings designed and built by Legg, were built on the block between 1886 and 1890.

Architecturally, the style of this house exemplifies a late variety of the Italianate style, which was popular in the United States largely between 1850 and 1880. The Italianate style emerged in England in the early 19th century as part of the picturesque movement. Early examples of the style in England and the United States draw heavily from informal Italian villas and farm houses, which often featured an asymmetrical plan with a central square tower. The style was featured in Andrew Jackson Downing’s famous pattern books and was widely employed in the United States by the 1860s. The style was adapted continually and grew into a uniquely American style. Its decorative features included bracketed cornices, double doors, pronounced window crowns and highly ornate porch detailing.

One of the American Italianate forms to develop was the town house; in St. Louis many of these houses make use of mansard or false mansard roofs that are appropriated from the Second Empire style. The Jones House embodies the informality of the Italianate style, although its stylistic touches are few. However, where it carries decoration — such as the cornice brackets, the brickwork band, mantels and door hardware — the house evinces the “decorative exuberance” that historians Virginia and Lee McAlester attribute to the style. The Jones House certainly embodies these characteristics, as did other town houses built in St. Louis in the 1870 and 1880s including many in Midtown.

Jerome Bibb Legg

Architect Jerome Bibb Legg was one of the most prolific local architects during the 19th century, as well as a real estate developer of sorts and a trade journal editor. For an architect once so popular, it is surprising how little is known about his life and how few of his works still stand. He is a somewhat enigmatic figure in St. Louis architectural history. Born in Schuyler County, Illinois, in either 1838 or 1839, he arrived in St. Louis in 1864 to attend Jones Commercial College. After graduation, he went to work for noted architect George I. Barnett, who taught Legg architectural drafting and principles. By 1868, Legg had entered the building trade as superintendent of construction for the Centenary Methodist Episcopal Church. He was soon designing buildings himself, and demonstrated a strong promotional ability. In 1876, he sent to 6,000 people a direct-mail advertisement of his services as a house architect, entitled Home for Everybody. His designs around this period included churches, the Manual Training School for Washington University and a paper bag factory for Samuel Cupples. In both 1883 and 1884, Legg received an impressive seventeen known commissions.

Legg’s prominence was clear in 1884, when he both obtained admission to the American Institute of Architects and saw construction of his design for the city’s Exposition and Music Hall, his most prestigious commission thus far. Around this time, he became the first editor of the influential Building Trades Journal, a position that both demonstrated his ability as observer of trends and also gave him space to showcase his designs to building professionals. By 1886, Legg was entering the height of his career. His involvement in the development of the 3700 block of Olive Street was not simply architectural, since his name appears as the property owner on three building permits issued on the south side of Olive Street in 1887 and 1888.

Architectural historian David Simmons says that Legg pioneered the design/build approach to development, often buying up land that he thought would be valuable and then designing and building speculative houses there. This approach paid off doubly, since Legg could use each project to sell a house and to showcase his architectural talents. In this period, his volume of work was such that he likely designed each work himself. It is likely that other families saw the Jones House under construction and commissioned Legg, who was known as both developer and designer, to build houses that they could buy finished from him. His business was also helped by the fact that he was also designing mansions in Midtown, like the L.L. Culver House at 3514 Delmar (1886), showing that he had the acumen to attract the city’s elite as clients. (His advertisements favored his costlier projects, since they were much more striking examples of his work than houses like the William Cuthbert Jones Home.)

As an architect, Legg was quite talented although his work never gained the critical acclaim that other architects obtained. His designs show that he was adept at many different styles, ranging from Romanesque Revival to Gothic Revival. Obviously, his stance as client-driven architect necessitated working in diverse styles, but his mastery of most was unusual. Legg’s wide and disparate range of work has garnered him a lower place in the local architectural canon than more visionary designers like his mentor Barnett. The architect also took on work in a wide geographical area, with a large out-of-state list of works in Missouri, Illinois, Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana, Kansas, Oklahoma and five other states. These works were spurred by his frequent advertisement and willingness to take as many jobs as possible. However, the dispersal of his projects likely weakened the impact of his legacy in St. Louis.

One of Legg’s more interesting later projects was designing temporary World’s Fair buildings in West Pullman, Illinois for the 1893 World Columbian Exposition. Locally, Legg went on to design (and develop) downtown’s long-gone Oriel Building, the Bofinger Memorial Chapel at Christ Church Cathedral and the now-demolished police stables in Forest Park. His practice continued to grow, and in 1895 he had opened four out-of-state branch offices to handle the workload, which included all sorts of building types but mostly residences. He abruptly resigned from the American Institute of Architects in 1899. He formed a partnership with Charles Holloway in 1902 that lasted only two years. After 1903, he maintained a St. Louis address but took on so much work in Cape Girardeau, Missouri, that he became widely associated with that city. He designed many buildings for Southeast Missouri State University, as well as a print shop in 1908 that is his last known work. Legg last moved to Pomona, California, where he died after 1911 (exact date unknown). The Jones House is one of only a handful of his St. Louis residences still standing.

William Cuthbert Jones

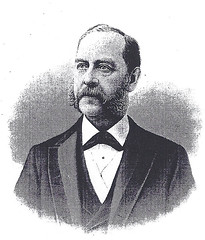

When William Cuthbert Jones (1831-1904) commissioned the house at 3724 Olive Street, he was nearing the end of an eventful life that included Civil War service, many years of law practice, political activity and a stint as a well-regarded criminal court judge. As a lawyer and political figure, Jones was a noted liberal and “has been known always as a man of sound convictions, but having at the same time broad and liberal views.†Jones was born in Kentucky and raised in Chester, Illinois, south of St. Louis. He was the son of Francis Slaughter Jones, a physician who had been a prominent Virginia planter, and Eliza Treat, who was the daughter of a federal agent. William C. Jones read law at McKendree College in Lebanon, Illinois before graduating in 1852. Jones soon traveled to his birthplace to study law at the office of Loving & Grider in Bowling Green. According to the History of the Bench and Bar of Missouri, Jones “pushed his studies so untiringly that within a year he was enabled to pass the examination that admitted him to the bar.†He briefly returned to Chester to practice law before moving to the larger city of St. Louis, where his prospects for success were greater. In 1856, Jones married Mary A. Chester of St. Louis, daughter of British parents. As was consistent with his other endeavors, Jones quickly made his mark in the city by forming a partnership with William Sloss. This partnership lasted one year, but Jones formed another longer-lasting partnership with W.W. Western of Hopkinsville, Kentucky. This firm practiced in both cities and endured for five years, until 1860.

After this dissolution, Jones had no trouble creating yet another partnership, with Judge Charles F. Cady. However, after the outbreak of the Civil War, Jones decided to enlist in the Union Army. Jones believed in the Union cause despite being a Democrat and the son of a former Southern planter. On May 8, 1861, Jones joined the Union Army as a captain of Company I, Fourth United States Reserve Corps. Jones served with this company in Southwest Missouri until it was mustered out in 1862. However, his desire to serve the Union cause was strong enough that he sought further enlistment, and became paymaster of United States Volunteers at the rank of major. On November 15, 1865, after the war had ended, Major Jones was mustered out after having served the Union Army through the entire war.

After the war, Jones apparently considered leaving the legal profession because he was averse to criminal practice. He entered into a steamboat and sign painting business for a year following the war, which was financially successful but physically exhausting. Jones returned to law practice in partnership with Charles G. Mauro, and remained in that partnership through 1871 when he formed a partnership with John D. Johnson. Jones’ interest in politics remained strong after the Civil War, and he became known as a liberal even as he retained membership in the Democratic Party, which was highly unpopular around St. Louis after the Civil War. In 1866, Jones sought the office of Clerk of the Circuit Court of St. Louis County as the Democratic candidate, despite inevitable defeat; in 1868, he was an active candidate for Democratic presidential elector in Missouri’s Second Congressional District. He was a firm believer in his party even as it was publicly unpopular after the Civil War. In fact, Jones was by all accounts a man of firm principles and unwavering convictions. Cox’s Old and New St. Louis notes that Jones could be found “sympathizing with and ready to fight the battles of the poor and lowly.”

Despite his fruitless political endeavors as both liberal and Democrat during the Reconstruction period, Jones was a trusted St. Louis attorney. He ran for a position as Justice of the Criminal Court in 1874, winning handily. On the bench, Jones was a respected figure whose four-year tenure was free of reversals. Jones is most remembered for his service as a criminal judge, and not without good cause. The History of the Bench and Bar of Missouri states:

…it is during his incumbency of this position that the remarkable intellectual qualities which he possessed, and which had already been recognized by his legal associates, became conspicuous. He had the art of ruling against an attorney without inviting animosity, sacrificing good will or suggesting partiality.

His notable cases included many murder cases and a vendetta assassination by five Sicilians. Through all of these cases, Jones was noted for fairness and gained widespread public respect. However, Jones elected to not seek a second term and returned to a civil law practice with Rufus J. Delano in 1878. In 1885, that partnership dissolved and Jones entered into practice with his son James C. Jones. Around this time, Jones purchased the land at 3724 Olive Street to build his final residence. Jones had lived for many years at 1522 Papin Street just south of downtown, but that area had lost its prestige by the 1880s. Many upper- and middle-class families who had lived around downtown were moving west to the Midtown area in this period. Jones’ choice of a location on Olive Street indicates that his wealth was stable but not enormous; the house that he built in 1886 on the lot reflects his position as an upper-middle-class attorney. Since all of the Jones’ children were grown up when the house was built, the home was most likely planned as the final house for Jones and his wife.

Jones continued practicing law until he began suffering from gastritis in 1901. He also served in the Legion of Honor, becoming “grand dictator” for the Missouri chapter. He died on January 22, 1904. After his death, Mary A. Jones moved to an apartment in the Central West End and the family eventually sold the house in 1909. In use for many decades as rental property of various configurations, the house managed to retain its historic character.

Over the years, the 3700 block of Olive fell into a pattern of decline like many other blocks in Midtown. Due to the grander architecture there, streets like Lindell, West Pine and Grandel managed to maintain their status longer than streets like Olive. Larger buildings including theaters, hotels and apartment buildings first replaced the old houses and tenements in the early twentieth century. In the latter half of the century, many were demolished just to clear land.

The character of the area around the Jones House has changed dramatically, and few residences remain. Two other homes remain on the north side of Olive on the block, and they are in disrepair. In 1981, Matthew Foggy purchased the Jones House and rehabilitated it, restoring windows, plasterwork, woodwork and hardware. Foggy maintains the William Cuthbert Jones House to this day as one of the neighborhood’s best-kept remaining houses. In 2006, Foggy contracted Landmarks Association of St. Louis to prepare a National Register of Historic Places nomination for the house. That nomination, prepared by this author and the basis of this article, led to listing of the William Cuthbert Jones House in the National Register on February 7, 2007.

Bibliography

City of St. Louis building permits and data engineering records. St. Louis City Hall, Microfilm Department.

City of St. Louis deed abstracts. St. Louis City Hall, Office of the Assessor.

Compton, Richard J. and Camille N. Dry. Pictorial St. Louis. St. Louis: Compton & Company, 1876.

Cox, James. Old and New St. Louis. St. Louis: Central Biographical Publishing Co., 1894.

Eberle, Jean Fahey. Midtown: A Grand Place to Be! St. Louis: Mercantile Trust Company, 1980.

“Former Judge William Jones is Critically Ill at His Home.” St. Louis Republic, January 16, 1904.

History of the Bench and Bar of Missouri. St. Louis: American Biographical Publishing Company, 1898.

Hopkins Fire Insurance Map: 1883.

Hyde, William and Howard L. Conard, Encyclopedia of the City of St. Louis Vol. 3. St. Louis: The Southern History Company, 1899.

“Judge William C. Jones to Be Buried Monday.” St. Louis Republic, January 23, 1904.

McAlester, Virginia and Lee. A Field Guide to American Houses. New York: Knopf, 1984.

St. Louis City Directories: Gould’s Blue Book, Gould’s St. Louis Directory, Gould’s Red-Blue Books.

St. Louis Daily Record. St. Louis Public Library, microfilm department.

Simmons, David interviewed by Michael Allen. June 27, 2006.

Toft, Carolyn Hewes. “Jerome Bibb Legg.” Landmarks Letter, July/August 1989.

Wayman, Norbury. History of St. Louis Neighborhoods: Midtown. St. Louis: Community Development Agency, 1978.

5 replies on “The William Cuthbert Jones House, A Midtown Gem”

Thanks for the history on this house. I’ve always loved the Italianate style, and this is definitely an attractive example of that aesthetic. I’m curious about the ’08 razing of the house at 3438 Samuel Shepard. Was that the one close by the burned-out church? Looking at the picture, one can clearly see the well-maintained shrubbery, and auto-read gas meter. Is there anything there now, or did SLU just do SLU’s thing: ie, land clearance?

Very interesting. I’ve long wondered how this house has managed to survive nearly alone on its side of the block.

Enjoying your appreciation & photos of these great places- lots of info here, thanks.

While walking by this morning, I discovered that the building just east of this one is being demolished. I don’t recall there being anything terribly interesting about this building, and it sure looked worse for the wear, but it’s still sad that the Jones house is the sole remaining structure on this end of the very long block.

[…] of Olive Street is down to just four historic buildi ngs, including the National Register-listed William Cuthbert Jones House at 3724 Olive Street and the Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge-designed Wolfner Memorial Library for […]