by Michael R. Allen

Our city’s enduring legacy to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. consists of the renamed Veterans Memorial Bridge (built 1951, renamed 1968) and the several-miles of combined Franklin and Easton avenues (renamed in 1968). The bridge is ever-functional and well-maintained, but the street honoring America’s greatest twentieth century political leader generally is a poor testament to the man. No matter how many miles of fresh concrete sidewalks and pink granitoid old-fashioned street lights go up on Martin Luther King Drive, the street’s condition generally is depressing, and most of its miles lack even basic beautification measures like street trees. (Of course, that street named for the slave-owning founder Thomas Jefferson is not much better off in many stretches.)

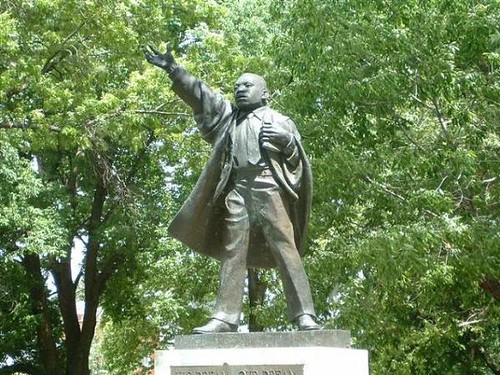

A better setting for honoring King is in the pleasant, tree-covered ellipse of Fountain Park. The placement even enshrines the changes in housing equality wrought in St. Louis’ west end neighborhoods in King’s lifetime. Fountain Park was the centerpiece of Aubert Place, laid out in 1857 and developed as a middle-class streetcar suburb on the edge of the elite Central West End. The neighborhood was segregated through the real estate practice of restrictive covenants until after the Supreme Court issued its ruling in the case of Shelley v. Kramer in 1948 — a case that originated in St. Louis not far away at 4600 Cote Brilliante Avenue. An earlier case of fighting deed restrictions dates back to 1943 at nearby Lewis Place, where African-American dentist Dr. Richard Layne successfully purchased a house on the restricted private place.

With housing restrictions dropped, Fountain Park and surrounding areas transitioned from white to largely African-American. African-American homeowners finally enjoyed the freedom to live where they wished to live in the city, and the spacious middle-class houses of Fountain Park were desirable dwellings. On May 7, 1978, Mayor James Conway and other leaders unveiled an eleven-foot bronze statue of Dr. King designed by Rudolph Torrini, who was on the faculty of Fontbonne University. Torrini had the bronze statue cast in Florence, Italy, and the casting is very fine work. King’s pose in the statue is heroic, with the subject’s right arm upstretched and his face expressing concentrated equanimity. Visiting the statue today, one will see a neighborhood whose future again is transitory.

Yet perhaps the best way St. Louis remembers Dr. King is through the preservation of those places where King spoke to audiences in St. Louis during his lifetime — places that actually were part of his life. King made several documented speeches in St. Louis between 1960 and 1963, and all of the buildings in which he spoke still stand.

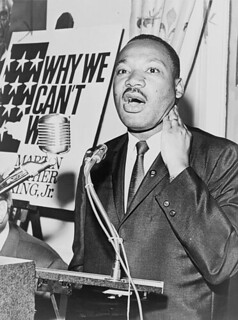

First, there is Washington Tabernacle Missionary Baptist Church at the southwest corner of Washington and Compton avenues, which is one of the city’s designated City Landmarks. King spoke at the church on May 28, 1963 to a large crowd; this was one of 350 speeches he made that year around the nation. This event took place on King’s tour leading up to the celebrated March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, during which King delivered his “I Have a Dream” speech on August 28, 1963. Washington Tabernacle, which is still going strong, purchased the massive limestone Gothic Revival church in 1926. The Washington and Compton Avenue Presbyterian Church built the building between 1876 and 1879 from plans by Charles K. Ramsey.

Then, there are the several locations to which St. Louis’ Jewish community invited Dr. King to speak. Not long after King’s famous speech in Washington, he returned to St. Louis to speak at Temple Israel, 10675 Ladue Road, on September 20, 1963. Speaking to over 3,000 people on the Shabbat between Yom Kippur and Rosh Hashanah, Dr. King spoke about the type of selfless love known in Christian theology as agape. King’s appearance came early in the life of the modernist synagogue, which had been completed in the previous year. Hellmuth Obata & Kassabaum designed the building, whose horizontal buff-brick box presents a sober base for an exotic tower sculpture by Robert Cronbach. Inside, the main sanctuary and auditorium are hexagonal with recessing walls that can draw the spaces together. The spaces had to be connected to accommodate the crowd gathered for Martin Luther King.

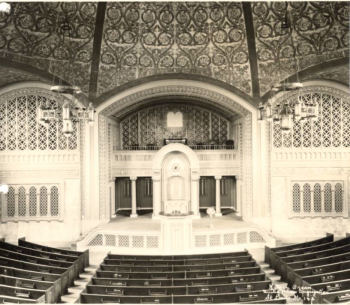

King’s Temple Israel appearance is not as well-known as his earlier speech at United Hebrew Congregation at 225 S. Skinker Boulevard in the city (now the serene home of the Missouri Historical Society Library and Collection Center). With support from Jewish Community Center (JCC) President Isadore E. Millstone, then-JCC Executive Director Bill Kahn invited King to speak at the annual Liberal Forum held on November 27, 1960. King’s work was gaining rapid national attention at the time. King chose his topic as “The Future of Integration,” drawing significant interest in the event. Rabbi Jerome Grellman of United Hebrew arranged to move the event, which attracted 2,500 people, to his spacious synagogue so that no one would be turned away.

Maritz & Young in collaboration with Washington University professor Gabriel Ferrand designed the domed, Byzantine-influenced temple on Skinker, which opened in 1928 and was used through 1989. At the time of completion, the impressive building was supposedly within the ranks of the nation’s three largest synagogues. King’s words would have reached the azure ceiling in the dome, which is emblazoned with gold patterning and the Star of David. Underneath the dome King received a 15-minute standing ovation.

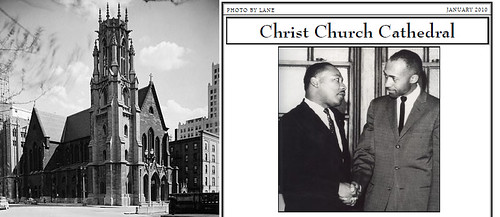

King returned in March 1964 to deliver a sermon at Christ Church Cathedral downtown. The Gothic cathedral, originally designed by master church architect Leopold Eidlitz, opened in 1867. Yet the Eidlitz plan for a 1,000-seat sanctuary had been adopted in July 1859. Construction of Christ Church Cathedral had been disrupted by the civil rights strife of one century prior, the Civil War. The city’s moral quandary was embodied by the actions of its leading citizens, including founding Christ Church founding vestryman James Clemens, Jr., who had aided his relative Major William Harney when Harney fled St. Louis after beating a slave to death in 1834 (Harney returned to be acquitted). Within the walls of a the sacred space built amid the convoluted Civil War St. Louis, King offered the eternal truth: “We must learn to love together as brothers or perish as fools.â€