by Michael R. Allen

St. Louis architect Marcel Boulicault’s name probably is unfamiliar to you, but a few of his works will draw an “ah ha!” or two. Boulicault is a designer whose contributions to Modern architecture in St. Louis are largely unheralded, but that needs to change. Boulicault (1896 – 1961) is best known for an obtrusive and despised addition to the St. Louis State Hospital, the Louis H. Kohler Building, which stood directly in front of William Rumbold’s domed 1869 County Asylum building. Boulicault also designed the building that became St. Louis Fire Department Headquarters, a major state office building on Jefferson City and other prominent works. Then, there is his patented electric tooth brush — which we will discuss in a moment. Boulicault’s buildings were creative, colorful (and a bit jazzy) but also purposeful — the best mid-century combination.

The career of Boulicault spans St. Louis’ golden age of classicism and revival styles to meet the local idiosyncratic application of International Style principles. Boulicault established the Office of Marcel Boulicault, Architects-Engineers in 1924. Boulicault had studied at the Washington University and at the Institute of Beaux-Arts in New York. The young designer apprenticed for well-known St. Louis architect Guy Study, ending up first as chief draftsman and then as partner in the short-lived Study, Farrar & Boulicault. Boulicault’s firm established itself as a specialist in federal and state governmental work, and was especially active designing for the US Army Corps of Engineers and various armed services branches. Boulicault’s firm also designed schools and office buildings and provided consultation of civil engineering projects like the Jefferson Barracks Bridge.

Boulicault, Modernism and the Displacement of Styles

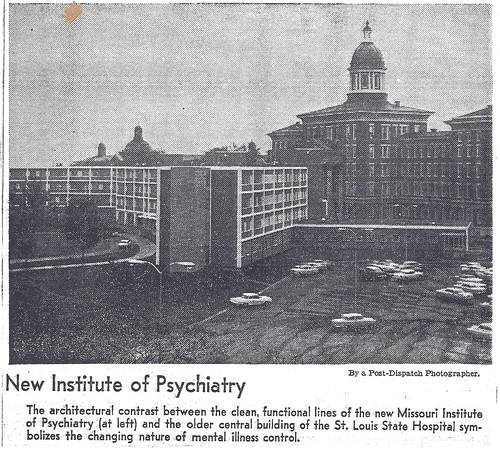

In 1962 the State of Missouri built the Kohler Building squarely on axis right in front of the State Hospital. For years, critics panned the site placement and the contrast of mid-century modernism with Rumbold’s classicism. Built St. Louis author Rob Powers summed up the critique best: “it was grossly misplaced, attempting to supplant the grand Classical facade of the main building with its comparatively unimpressive International Style forms.” Later, in 1998, the state of Missouri demolished the building to restore the front of the “Old Main” building by Rumbold. Yet the Modern movement building likely would have found some love from today’s preservationists, who might have swooned over the modern form and colorful spandrel panels.

The Kohler Building, like Boulicault’s best buildings, had a feeling — that is, it was not a picture-perfect monument designed overwhelm people, but an artfully-designed tapestry that conveyed warmth and texture. The reinforced concrete frame was clad in orange-red brick on the sides and rear, while presenting a curtain wall face studded with colorful metal spandrel panels. Built as a four-story building, the building later gained two stories and extensions to the rough-faced limestone stair towers at the ends of its wings. Those wings stretched outward as if to embrace anyone who approached form Arsenal Street. Although the Kohler Building blocked the view of Old Main, it made every effort to be inviting – an important trait at a psychiatric institution. At the same time, the building had a proto-Brutalist emphasis on form akin to the contemporary Richards Medical Laboratories at the University of Pennsylvania designed by Louis I. Kahn.

Of course, the Kohler Building actually served a pressing need. When Louis H. Kohler had become superintendent of the State Hospital in 1941, there was 120% overcrowding and space was desperately needed. Unlike today, when the campus of the State Hospital has ample open space, in 1962 the site was constrained by two large wings built in 1907 (now demolished). Perhaps the building could have been built closer to Arsenal Street to have avoided such close occlusion of Old Main, but instead it was placed toward Old Main to preserve the open lawn that created a serene, green approach to the buildings of the hospital. That lawn has been encroached upon by post-1998 construction to the extent that the Kohler Building’s presence seems a lot less objectionable now.

Upon demolition, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch casually stated that the Kohler Building was “architecturally dated” as if Rumbold’s grandiose Italian structure and its later heavy neo-classical portico were somehow in keeping with 1990s architectural vogue. Current cultural resources practices would have realized that the Kohler Building’s layer of architectural history represented an important later era of institutional advancement, and association with the career of a significant architect. Yet in 1998, just 15 years ago, such considerations were not made by any local or state preservation officials or by preservation advocates. The consensus was that modernism was “wrong” for State Hospital, and so one of Boulicault’s finest buildings fell to the wrecking ball. (By contrast, Boulicault’s 1937 Infirmary Building at the Missouri State Hospital No. 3 in Nevada, Missouri is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places.)

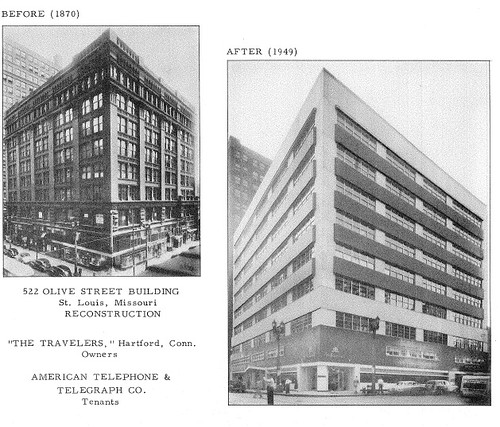

Fitting the advancing erasure of earlier eras endemic to American architectural practice, Boulicault himself was no stranger to the idea of removing “architecturally dated” designs. In 1949, the Travelers’ Insurance Company of Hartford, Connecticut hired Boulicault to design the recladding of its eight-story office building at 522 Olive Street downtown. Boulicault removed any vestige of the building’s late 19th century commercial style, and repackaged the building in a handsome minimalist grid of granite, limestone and steel. Today, the site is buried beneath the icon of a later era, Metropolitan Square, whose granite-clad, green-roofed Postmodern bulk may struggles to not be defined by its 1989 date of construction.

Some Remaining Works In and Around St. Louis

Other Marcel Boulicault buildings from the Modern era still stand. Boulicault designed the Wellston High School in Wellston, completed in 1941 at a cost of $550,000. The two-story red-brick building draws not from modernist design, but the paired reverence for classicism and the Art Deco style that can be seen in better-known St. Louis buildings like the Main Post Office (1937, Klipstein & Rathmann) or the Municipal Auditorium (1932, LaBeaume & Klein). Wellston High School has a classically-oriented pedimented entrance bay of limestone, with elements like acanthus atop the pediment, classical pilasters and frieze keys run through the geometric language of Art Deco. Today, Wellston High School sits vacant and in danger of demolition, but both its firmness and grace remain wonderfully evident as ever.

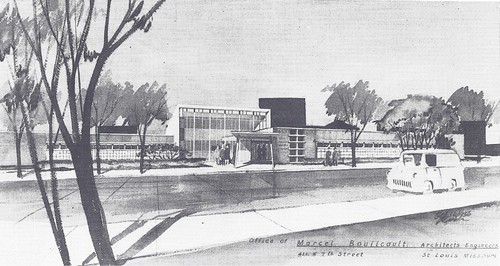

Boulicault’s best-known remaining local building probably is the Fire Department Headquarters at the southwest corner of Jefferson and Cass Avenues in the north St. Louis neighborhood of JeffVanderLou. Completed in 1955, the long, low flat-roofed building was built by the City of St. Louis as the Jefferson-Cass Health Center, a public clinic built in part to serve the families of the Pruitt and Igoe housing projects then underway across Jefferson Avenue. The clinic offered comprehensive child health care, prenatal classes, obstetrics and family planning, X-rays and TB treatment. The building breaks up its boxy form with a pronounced canopied entrance in a two-story center section. The low wings make use of light brick, light terra cotta, ribbons of small windows, a course of red enamel bricks and a red terra cotta panel with applied stoned multi-level cross that emphasize the building’s original medical function. Like the Kohler Building, this is a work of colorful but restrained modern design influenced by the International Style.

Military work by Boulicault remains around St. Louis, much of it not inventoried. Boulicault and his associated structural engineer Ralf Toenstedt designed a fairly unremarkable storage box for the 85th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron (FIS) at Scott Air Force Base. Completed in 1953, the building houses small arms and was located near the readiness hangars of the FIS. Facility 512, as it is numbered, is not eligible for the National Register of Historic Places and follows conventions for its building type, but it is an interesting relic of Cold War culture. Every Air Defense Command FIS facility had such a building.

Boulicault in Jefferson City

Boulicault designed two office buildings located in Jefferson City for the State of Missouri, and both stand in severely altered forms. The State of Missouri decimated the integrity of Boulicault’s Missouri Employment Security Central Office Building at 421 E. Dunklin Street in Jefferson City. Completed in 1952.

The horizontal mass is emphasized through wide ribbons of steel windows, and a continuous brick spandrel between the first and second floors. Exaggerated brick end walls had stone-framed windows. The minimal treatment is in keeping with the International Style, as is the building’s one ornamental gesture: an upswept thin-shell concrete canopy at the entrance. Today, the building is clad in heavy brick and looks almost nothing like Boulicault’s design.

The 14-story Thomas Jefferson Building, a state office building at 205 Jefferson Avenue across from the Governor’s Mansion in Jefferson City, was completed in 1951. Boulicault dramatically sited the building at an offset angle, so that the street corner on which the building sat was dominated not by a big box but by a striking angular bow. The Jefferson Building was a strong example of the influence of the International Style in Missouri architecture. Boulicault’s cubic form and window banks are austere and elegant, with a timeless sensitivity. The glass podium and (unbuilt) projecting entrance canopy are typical of the era, comparable to contemporary works like Harris Armstrong’s Magic Chef Building of 1947 which seems to be a distinct influence) and SOM’s Lever House in New York City (completed in 1952). Unfortunately the State of Missouri removed the transparent original windows and replaced them with tinted glass, and reskinned the upper floors in metal panels, mitigating the original architectural character.

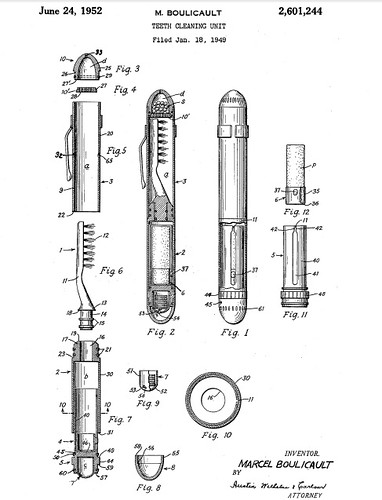

The Pocket Electric Toothbrush

Boulicault’s modern design practice extended to industrial design as well, and produced an early electric tooth brush patent. On June 24, 1952, the United States Patent Office granted patent #2,601,244 to Boulicault for the design of a “teeth cleaning unit.” The invention essentially was an electric tooth brush that fit into a small, pen-like streamline case. According to the application, “the tooth brush and all accessories necessary for the proper care of the teeth are assembled together in an attractive and compact unit which may be conveniently carried in the pocket or purse.”

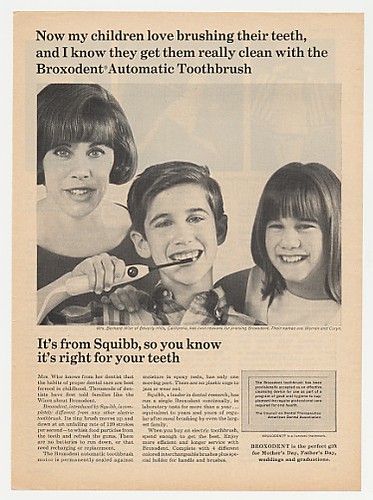

Boulicault had previously received two patents for similar devices in 1949, and reported working on such a project since 1945. This work came pretty early in the period of modern dental hygiene: the nylon bristle tooth brush that we know and use today was not introduced until 1938 by Dupont de Nemours. The first electric rotating tooth brush design may date to 1939 in Switzerland. The prototype mass-market Broxodent electric brush appeared in 1954 and was marked by Squibb after 1960.

There never was mass production of electric tooth brushes that fit inside of pockets and purses, making Boulicault’s invention more of a curiosity than anything. Still, the acumen displayed in the design of a strange but very innovative device shows that Marcel Boulicault had a mercurial mind when it came to designing in the modern age. Boulicault’s surviving buildings are another testament to that mind. When the annals of mid-century modernism in St. Louis are fully written, there is no doubt that Boulicault’s name and work will be included.

3 replies on “The Mid-Century Modernism of Marcel Boulicault”

Thank you so much, this is very interesting! Mr. Boulicault was a cousin of mine, and I’ve always been curious about his work.

I completely disagree with the assessment of Boulicault’s Kohler Building; it was a mistake when completed and was a welcome demolition. I usually do not comment on posts, preferring to either enjoy them or dislike them in silence, but the posts on Modern Architecture do a dis-service to preservation. This site’s love for Modern Architecture obscures the fact that nearly all Modern Architecture was and remains a mistake, a cancer on the landscape. The Kohler Building was a mistake, obscuring a wonderful, monumental structure with an uninspired set of boxes. Office buildings such as the Thomas Jefferson Building were initial denegrations to the urban street wall, creating the initial “public plazas” mindset that would lead to the many mistakes in St. Louis and elsewhere. Modern Architecture in that vein should not be preserved.

While I appreciate the work on this site about actual historic architecture worthy of preservation (such as the blocks of endangered and maligned domestic architecture throughout St. Louis), I feel that this site’s advocation in favor of preserving Modern Architecture is merely propagating mistakes from decades ago and making those mistakes permanent.

“…nearly all Modern Architecture was and remains a mistake…”

To say that this is hyperbole would be an understatement. Anywho…

The Kohler building reminds me of this, the Piamio sanatorium in Finland:

http://rwhitespace.com/content/research/aalto/big/5_sanatorium.jpg, http://rwhitespace.com/content/research/aalto/big/6_sanatorium.jpg, http://rwhitespace.com/content/research/aalto/big/4_sanatorium.jpg

Though I must say that in execution, and in contrast to the rendering, the Kohler as built was a somewhat imperfect conclusion.

Interesting that you mention the possible demolition of Wellston High School, seeing as it was probably built with funds from the Federal government, at least in part, as part of their response to the first Great Depression. What a criminal waste that would be, were it to happen. But, then again, we’re ‘Merkins: waste, it’s what we do. Just another aspect of the violence of our modern culture.