by Thomas Crone

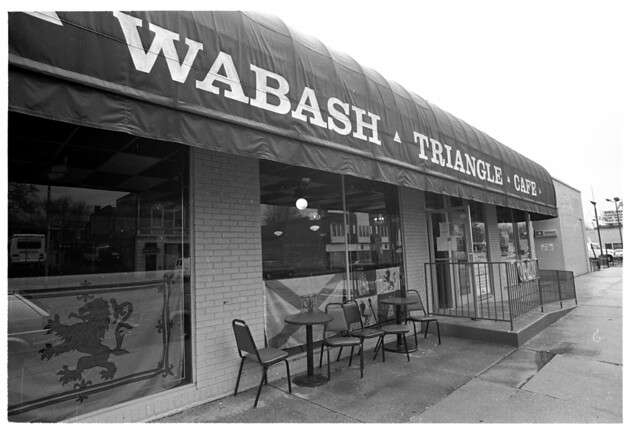

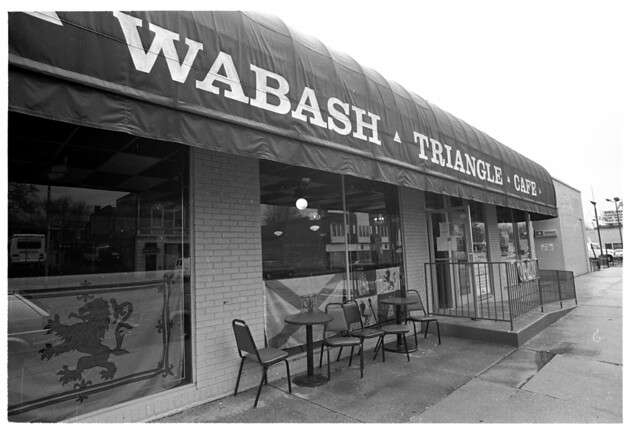

The Wabash Triangle Café. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

The Wabash Triangle Café. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

The Wabash Triangle Café burned on Friday, March 18, 1994, its last day of business. Though that date’s one I needed to look up, the timing’s also quite vivid in my memory. I was in Austin, TX, on that morning, attending the South by Southwest Music Festival. Though I’d have a couple more days of music, Shiner Bocks and cavorting ahead of me, I distinctly remember that the phone call from home, a co-worker at the RFT detailing only the barest facts about the Wabash fire. It was a call that pretty well squashed any fun for the rest of the weekend.

Calvin Case behind the espresso machine. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

Calvin Case behind the espresso machine. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

For a chunk of my early 20s, the Wabash Triangle was my default destination, a venue that brought nightly music and culture to the very footprint that would eventually become the Halo and the Pageant. In the golden days before cell phones and instant communication of all sorts, it was the kind of place you could roll into with the reasonable assumption that something interesting was happening and someone you knew would be home. And “home” is the feeling that the place gave off. Part diner, part coffeehouse, part bar and full-time oasis to the misfits, the Wabash allowed for interesting conversations to blossom and for friendships to grow in a room that never quite felt like the rest of that moment’s St. Louis.

Partially, that disconnection was a result of location. Though owner Calvin Case had a building found just east of the University City Loop on Delmar, the mental and physical geography of Delmar in the early-’90s was different than today. Few, if any, of the Loop’s regulars walked as far east as the Wabash. If you bought books at Paul’s, or caught a movie at the Tivoli, or headed to Cicero’s for a band-and-pizza, you tended to stay on the west side of Skinker. Without the Metrolink stretching the block, and with east-side-of-Skinker destinations like Pi and Big Shark Bicycle far-off in the future, the Loop really was limited to University City’s piece of the map. And those heading from down the busier end of Delmar often drove the few blocks, rather than heading there on foot.

The area may’ve been a smidgen rough, but once inside the mood was always upbeat. Except when it wasn’t. On some nights, slam poets took over the entire space and the energy was raw and palpable. Other days, especially in the early evenings, you’d find just a couple people playing board games in a corner, while Calvin held court with his tiny cast of workers at the bar. Most days, Calvin was up; some days, Calvin was down. Kinda depended upon business. And on a lot of business days, the dozen customers each buying a cup of coffee didn’t exactly keep the register ringing.

Calvin Case and the chef. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

Calvin Case and the chef. Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

Even before the fire, there was always the vague sense that the Wabash Triangle could be gone. Calvin tried everything to make the space click. Early morning hours. Late hours and some Sundays. Menu changes a’plenty, along with “a real chef” in the kitchen. Matching the crazy-quilt interior, musicians of every possible stripe were booked, with varying degrees of success, from Calvin’s preferred folk to hardcore to indie.

In that space, they performed to an odd cast of regulars and an equally odd decor. Dozens of Michael Draga photographs ringed the ceiling of the former automobile showroom. A huge painting of western pioneers dominated the wall behind the stage. And throughout the venue, a mish-mash of retro furniture, true antiques and alley-rescued castoffs provided all the bohemia any post-collegian could want. The odd, low-slung building was even attached to an auto glass business, which seemed odd at the time, but now seems just right. Describing the look’n’feel of the Wabash is tough, but if you’ve been to a show at the old Frederick’s Music Lounge, or the newer Fred’s Six Foot Under, you’d have an idea of the vibe, with the substitute of Calvin Case for Fred Friction. Calvin was the constant, consistently tossing out ideas, suggestions and bits of collected wisdom.

And while Calvin provided the room’s heartbeat, there were many elements of the space that made it what it was, from the staff (Beth, Rich and Brett), to the crazy clientele, to the impression that you were crashing a space that not everyone knew about. Just blocks from the center of alterna-culture in St. Louis, there you were, in the City’s true underground.

To date, I’ve shamefully not yet seen David Dandridge’s new documentary, The Roof is on Fire, a look-back at the room and its then-prolific slam scene. Maybe it’s because I have a feeling that the memories would be a little bit too… much. With due respect to the Way Out Club, the self-professed “home away from home,” there are only so many places you can truly call that in your lifetime.

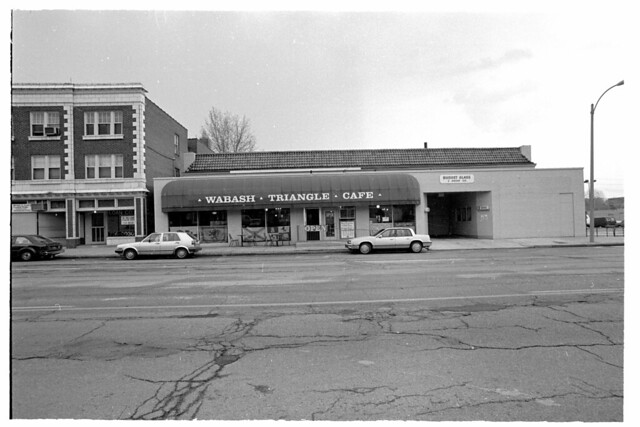

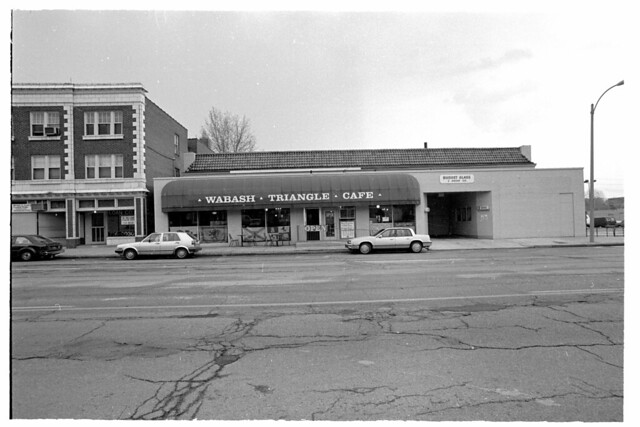

The Wabash Triangle Café. The three-story building at left still stands, Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

The Wabash Triangle Café. The three-story building at left still stands, Photograph by King Schoenfeld.

For a couple of too-brief years in the early ’90s, the Wabash Triangle Cafe was my home.

I miss that special place, still.

Thomas Crone publishes creativesaintlouis.com; and hosts “Silver Tray” on KDHX, Fridays @ noon.