by Michael R. Allen

The dean of New York history, Kenneth T. Jackson, recently published a salvo in the New York Times intended to advance the argument that New York’s neighborhood preservation movement was stifling the city’s chance to build new high rises. In his article “Gotham’s Towering Ambitions” Jackson argued that without new office buildings, New York could fall behind other global cities.

This week, Roberta Brandes Gratz published a very sensible, lyrical response to Jackson in The Huffington Post (“Urban Change to Believe In”. Gratz challenged Jackson’s view, arguing that New York has experienced a transformative change without giant new buildings –and that change is more impactful and long-lasting. In fact, Gratz argues that those voices Jackson called obstructionist actually are at the forefront of celebrating urban change.

“[I]t is time to celebrate the new kind of change that manages growth by balancing old and new and recognizes that the new derives its value from existing in the midst of the old,†writes Gratz, in an essay that captures what actually covers a larger context than just Manhattan. The larger context is the future of the American legacy city, and the past few decades of incremental urban change that has stabilized cities once in free fall.

While St. Louis is several shades removed from the cosmopolitan metropolis of New York, the lilt of development debate has a few parallels. While New York is a high-demand market, St. Louis city remains fairly low-demand. In fact, we may still be losing residents. Yet our mythology of growth keeps city officials chasing big projects – not skyscrapers, but strip malls, warehouses, entertainment “districts,” and occasionally sports facilities. None of these projects seems to be very good at embracing the existing city fabric, and we are often told than none can afford to be – X number of jobs is more important than anything else.

The rallying cry in St. Louis is not a Jacksonian ode to the skyscraper jungle we could become, but rather the hegemonic official searches for “jobs†and “retail.” As Jackson criticized preservationists, St. Louis developers and officials are prone to blame a similar crowd — preservationists, urban design activists, boulevardiers — for the supposed push-back on projects like Northside Regeneration and City+Arch+River. In both cities, the supposed rabble of agenda-pushing activists actually looks more like average citizens demanding accountability and protection of their neighborhood quality of life. At the recent TIF Commission hearing on Northside Regeneration, none of the speakers against the project — panned as “barking dogs” by the developer — was a preservation or urban design activist.

The powers that want-to-be succeeded in attaining green lights for Ballpark Village, Northside Regeneration and City+Arch+River. If anything, the rallying against elements of these projects ultimately had little impact. Certainly, critical voices have been accused of tampering with all three of these projects, yet in the end the slow pace is only the fault of the projects’ own designers — and the forces of the real estate market. Perhaps people just don’t want these projects in the same way they want rehabbed houses on tree-lined streets, or restaurants in imaginatively adapted spaces, or small-scale public spaces like Citygarden that are based on delightful experience. Why do officials keep chasing the urbanist magic bullets in the name of economic growth, when these projects aren’t truly growing the city?

Gratz points out that New York’s meteoric spreading gentrification, which transformed a late mid-century SoHo loft trickle into a multi-borough flood, balanced and slow development has made the city more liveable and the values of buildings higher. The same dynamic, ever-slower, operates in St. Louis. The city’s evident comeback has little relation to mega-projects. Neighborhood revitalization has had few subsidies and little in the way of political favors. That’s why it makes so much economic sense — it is demand-driven and has an output greater than its cost.

While city leaders decimated row houses in Mill Creek Valley for short-lived low-density urban “renewal” in the 1950s and 1960s, rehabbers set into motion long-term, sustainable reclamation of Soulard, Lafayette Square and the Central West End. Decades later, that momentum is evident in the spread of stabilized fabric, and in the amount of infill construction taking aim at the empty spaces in the early rehab neighborhoods. Earlier rehabber protections in the form of historic district ordinances are accommodating of change, too. I live in Shaw, where we have a local historic district with fairly strict standards. Two blocks away, in a few months some very different contemporary housing will rise as DeTonty Commons — and the Preservation Board approved the project after some careful review against our local historic district standards.

Today, from Cherokee Street to Old North to Fountain Park to Bevo, people are still doing the same thing: rehabbing houses, opening small businesses, and rebuilding the density of activity the neighborhoods’ architectural frameworks still can support. The litany of hot-shot big-ticket projects, from St. Louis Centre to Chouteau’s Lake, have either failed to survive despite high subsidy or have never materialized at all. The supposed game-changing projects of today languish, and force their success stories through mediocre over-priced “development” that likely removes more tax dollars than it ever returns.

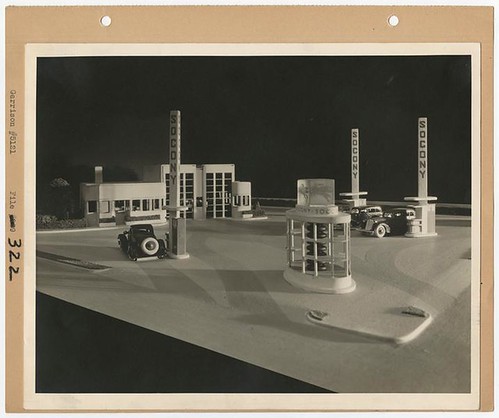

The city’s only new high-rise built during the market boom, downtown’s Roberts Tower, was completed only to sit empty before going to foreclosure. Meanwhile, the Tower Grove Farmers’ Market grows and thrives amid the influx of families to the area around Tower Grove Park in south city. The McRee Town neighborhood, just twelve years ago considered one of the city’s most dangerous parts, now boasts a patisserie across the street from a wine bar in a converted gas station. Picnic tables and benches in O’Fallon Park are hard to come by following major park improvements in the last years, and that is not even when the annual summer concerts are going. All over the city, incremental change has built community, while high-cost development has either floundered or simply supported changes already underway.

Citizens who are skeptical of big fixes for their cities, in St. Louis or New York, aren’t naysayers. They are stewards of the gradual transformation of legacy cities that is ground-level, economic and communitarian. They embrace change. These are people who say yes to continuing to develop cities in ways that are responsive to their users, so that the profits of development are socially distributed rather than individually concentrated. Development is not inherently a threat to smart urban growth, but when it ignores actual economic demand and social needs, it can be everyone’s worst enemy.

New Yorkers may see tall towers as a threat. In St. Louis, the biggest threat to sustainable change is more likely embodied in the Ballpark Village parking lot. If the vernacular red brick building has become the symbol of what St. Louis adores, it’s not so much because of nostalgia or fanaticism — it’s because that building represents a bona fide economic and visual asset built at a human scale (not an ethereal promise based on a profit motive or an inflated sense of civic identity). The alternative often is too ugly to love. As Gratz writes, “Change worth celebrating values the distinguished and ever functional old and shuns the new for the sake of what’s new, too often banal and surely big.”

Architect and friend Ann Wimsatt often talks about the “four corners” urbanism that St. Louisans like, embodied best perhaps by the intersection of Euclid and Maryland avenues. There, the intersection is held by four historic buildings, none higher than four stories and three of which are brick. All have wide ground-level storefronts, which are full of activity into the night. Here, the buildings are supporting human activity — buying, selling, shopping, dining, conversing — in approachable forms. Anything new that could be as functional, attractive, storied and beloved as that intersection would be a hit in St. Louis. Perhaps city officials hear the voices at public meetings as growls, but I hear them as odes to the urbanism that works — and that we already have.