by Michael R. Allen

On January 10, the city’s Building Division issued emergency condemnation (for demolition) of the landmark building at the southeast corner of Page and Kingshighway boulevards. The Roberts Brothers Properties LLC owns the building and two adjacent two-story commercial buildings. A motorist struck and toppled the corner iron column on the building, which has been vacant for a year or two since Golden Furniture moved out. The Building Division has not yet followed up with any emergency demolition permit, although such action is almost certain. (Curious Feet St. Louis reported the news awhile ago.)

The loss of the corner column has already led to significant shifting of the building’s weight downward at the corner. The brick wall shows how the bottom of the second floor is pulling downward. At the moment, this is a problem that can be corrected with a jack or another iron column. (What happened to the building’s original column? Why not just re-install it?)

The situation has become one of those self-fulfilling prophecies that dampens one’s attempt to be hopeful for the commercial buildings of north St. Louis. Here we have beautiful commercial buildings that define a major intersection, and which were in use until recently. A big-time owner lets leases lapse, perhaps plotting demolition for replacement with some silly strip mall like the owner’s project across Page. Then, an accident happens. The Building Division steps in, goes through its procedures, while the owner does nothing. The owner does not jack up the corner with a support, which would avert further damage. The corner pulls down, triggering a major collapse. The Building Division rushes in to get demolition started. The owner sits back and lets events unfold, while hatching plans for new development. Preservation and minimal code enforcement never had chances.

This is frustrating because the building is elegant and obviously in decent shape. The Roberts brothers could view ownership of these buildings as great fortune — they get to possess unique historic buildings at a major intersection. They get to take a step to ensure that north city retains the level of historic character that makes real estate in south city so valuable. They could renew a cultural resources and pave the way for long-term rising of real estate values in north city, instead of falling into the temptation to build a short-lived retail center with short-term pay-off.

The Building Division is not a preservation agency. Yet the Building Division could step in and make the owners put a support at the corner. After all, that’s stipulated by the building code. The owners’ intentions should not influence the Building Division’s enforcement. Whether or not the owners want to tear down the buildings is a moot point until there is a demolition permit. Up to that point, the division should seek to force the owners to make repairs of structural necessity.

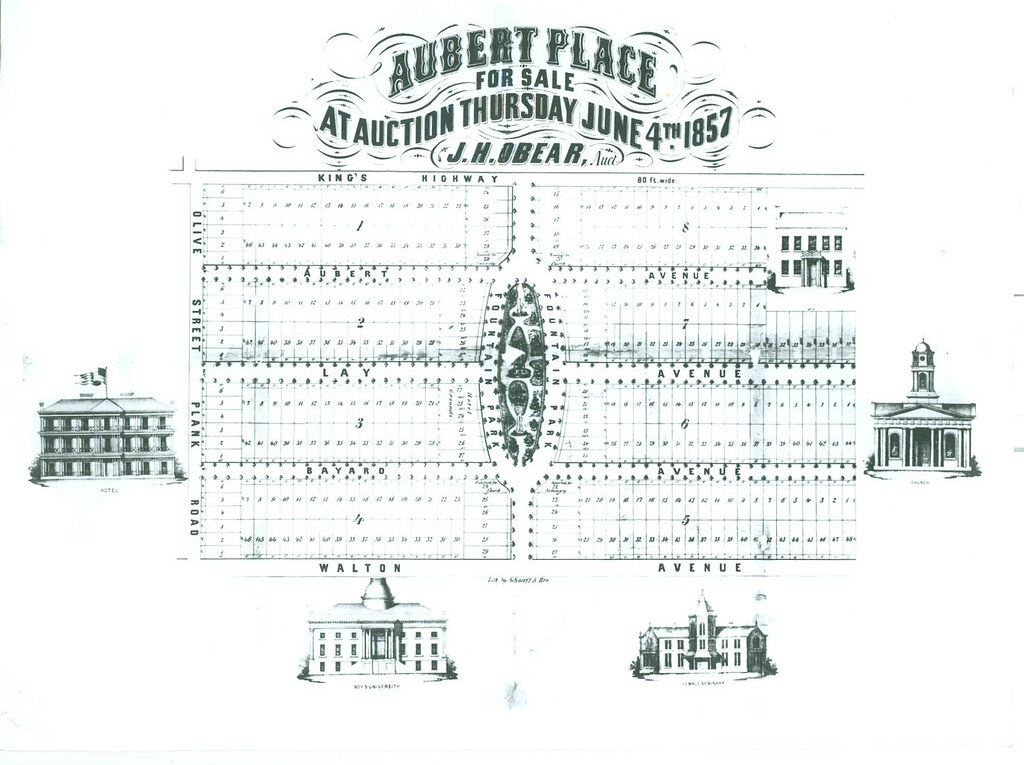

Beyond code enforcement, preservation makes sense. Page Boulevard has many threats to corner commercial buildings at the moment, and has already lost several. Kingshighway north of Delmar is likewise losing its lines of commercial buildings. Presence of anchor landmarks sometimes makes the difference between people remembering having been to a neighborhood or not. These buildings are in Fountain Park, which possesses a memorable interior. Yet its perimeter would lose a little less character with the loss of these buildings. The oval park, the famous curved storefront, the historic homes, schools and churches present a distinct and impressive identity. A corner strip mall, festooned with a developer’s name, with litter blowing across black asphalt in front of squat little retail boxes demonstrates no distinct character and in fact could have a blighting effect on neighboring block that retain their character. Fountain Park is a little less remarkable with every lost landmark.

These buildings are inherently remarkable, too. Built between 1904 and 1908 from designs by architect Otto J. Wilhelmi, the group shows a mix of modern sensibility and Victorian-era stylishness. The two-story buildings are rather plain expressions of the commercial storefront form while three three-story building is a blend of stark iron storefronts, paired Romanesque windows with pronounced archivolts on the second floor and windows with terra cotta keystones and voussoirs that suggest the Georgia Revival style. Then there is the white glazed terra cotta ornament of the parapet, which draws upon Classical Revival styles and features a projecting acanthus and the corner and near the south end. The building permit for the building mentions a galvanized cornice, long-gone. All three buildings are clad in buff speckled brick prevalent in north city commercial architecture of the period. In all, the buildings are unusually eclectic for this part of north city — and that statement means a lot. If only the owners recognized the treasures that they already have.