by Michael R. Allen

Chicago’s renegade activist Richard Nickel, whose passion inspired a generation of preservationists, once stated: “Great architecture has two natural enemies: water and stupid men.â€

Too bad neither can be avoided on this planet.

Whether the onset of actual demolition of the Graham Paper Company Warehouse — known colloquially as “Cupples 7” — supports this theory is a sour-grapes hornet’s nest, but some things are certain. The building’s physical death was due to water. Lots of water over lots of time. And that time, presided over by men ranging from officials at Washington University to developer Kevin McGowan to former Treasurer Larry Williams, was long enough that the water could have been stopped. Ten years ago, a temporary roof may have cost as little as $100,000. Today, stabilization would cost over $5 million and demolition at least $250,000.

This demolition could have been avoided, and shows the folly of letting city agencies spend tax dollars on land acquisition and demolition. We won’t know the real costs of demolishing the building until later, when the potential profits and revenues generated by an elegant five-story mass will linger only as ethereal presences invisible to most eyes. What will be visible will be a fenced-off patch of grass and the cold hard slab of a parking garage staring out at pedestrians.

Still, this is a teaching moment. This week Mayoral Chief of Staff Jeff Rainford told the St Louis Post-Dispatch that the city was ready to learn lessons from the demolition. Here are a few that this preservation practitioner sees:

1. New ordinances won’t save buildings. There has been talk of a “demolition by neglect†ordinance. While politically the stuff of good theater, such an ordinance is redundant. The building code already makes willful neglect illegal. The Building Division and the City Counselor struggle to enforce the code with limited resources. Instead of a new wrist-slap law that will cost as much to enforce as it would collect (see the city’s dubious “Vacant Building Registration†ordinance), the city needs to do smarter things.

2. Code enforcement could be improved. Technically, having a giant hole in the roof of a building – or a collapsing back wall – is illegal. Cities like Baltimore have targeted code enforcement to deal with vacant property. St. Louis can do the same.

3. Existing redevelopment agreements offer the city plenty of leverage, but the city needs to use it. Cupples 7 actually was governed by a redevelopment ordinance for a multi-building project. Nowhere did that ordinance, passed by the Board of Aldermen and signed by the Mayor, spell out any requirements for stabilization of the worst building in the mix. The city can’t force property owners to save their buildings — but when an owner comes to the city looking for incentives and subsidies, the city has the power to set conditions that safeguard buildings. The city has an agency, the Cultural Resources Office, that can consult on these agreements with professional expertise on issues like stabilization and demolition.

4. The city has another chance to prevent another “Cupples 7”: Northside Regeneration. This week the Tax Increment Financing Commission approved a public hearing on August 28 for activation of Paul J. McKee Jr.’s $390 million tax increment financing package for Northside Regeneration. Northside Regeneration owns scores of historic buildings, including the James Clemens Jr. House — the city’s only pre-Civil War mansion to sit vacant. Water is working on the Clemens House. Why won’t City Hall use leverage to get a roof on the building?

5. The city needs to follow its own Sustainability Plan. The plan itself should have guided a different outcome for Cupples 7. Under “Urban Character, Vitality & Ecology,” Objective F, Strategy 4: “Provide resources to preserve and prevent demolition of key historic structures that do not have parties immediately interested in investing in the building.” The plan lists the time frame for implementation as “short term.†It’s unfortunate that the first test of this part of the new plan leads to a failure by multiple city departments to follow the plan. Yet there are other tests ahead: Crunden-Martin Building 5, St. Mary’s Infirmary and smaller buildings across the city.

6. Create policies that recognize that there are two options for buildings: Demolish OR repair. While $250,000 might not have saved Cupples 7, it could have helped. The demolition budgets for smaller buildings often are higher than the cost of roof patches, temporary gutters and other short-term repairs. Rainford discussed the possibility of using demolition money to repair buildings and then placing a lien against the owner. Preservationists and neighborhood activists have called on the city to do that for years – what a relief to read that the mayor’s office is on the same page. Whatever that takes, let’s do it.

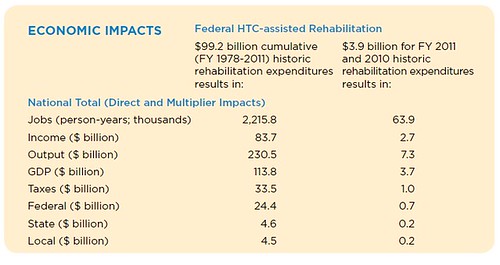

7. Preservationists need to be willing to help the city raise money. This isn’t a lesson for City Hall, but for all of us who are looking to the city to change its ways. We need to change our own. This city lacks a preservation fund for repairing buildings, ever since Landmarks Association of St. Louis killed its Revolving Fund in the early 1980s. Rainford talked about creating a fund administered by the city. That would be great, but preservation advocates need to do their part and building funding mechanisms instead of complaining about city inaction. The same part of the Sustainability Plan quoted above implores the city to “Establish a local funding stream for preservation work which directly contributes to the City’s economic growth.” Such a stream won’t build itself, and if it is not attenuated with private donations, would never be of use on the scale of a building like Cupples 7. We have to help the city build the fund.

We can’t stop the rain, and we can’t keep property owners from making bad decisions. Yet coordinated, strategic vacant building preservation efforts — wiser code enforcement, smarter redevelopment agreements, changes in city demolition funding and preservation community hustle — could send water and stupid men on the run.