by Michael R. Allen

The relocation of St. Louis University’s School of Law into a transformed building at Tucker and Pine streets has helped Tucker Boulevard regain some its lost title to being downtown’s most important north-south street. Students and faculty circulate around what was once one of the city’s most tragic and downright ugly modernist boxes, giving Tucker Boulevard hopeful human energy. New cafes and restaurants suggest that the law school could have a catalyst impact.

Should the footsteps of the repopulated species of the Tucker pedestrian march toward Washington Avenue, they will pass by one of the street’s proudest achievements, the neoclassical mass of the Hotel Jefferson. Located between Locust and St. Charles streets, the old hotel is punctuated by climbing bay-window appendages and up-top truncated floral ornament that once cradled rounded windows. The Hotel Jefferson proclaims an architectural imperiousness befitting its origin as a hotel built for the visitors to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in 1904.

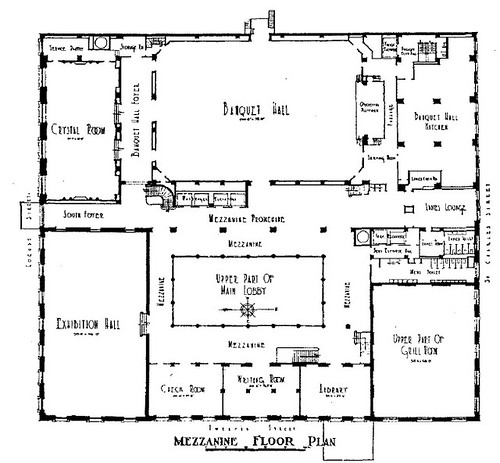

In 1928, ahead of the Depression, the hotel developers built a major addition to the hotel designed by Teich & Sullivan of Chicago. Teich & Sullivan redesigned the lobby of the original Barnett, Haynes & Barnett-designed building, creating an overlook to the first floor lobby encircled by balustrade. The mezzanine level became the home of two new major public spaces in the new addition.

Boarded-up base keeps pedestrians from glancing into its hidden inner mysteries — but hopefully not for long. Those who know the building for its final use, a warren of cheap studio apartments called the “Jefferson Arms,” might not suspect there are any mysteries lingering beyond untold mortal affairs (best left untold). Wrong. Inside of the old Hotel Jefferson is a lost golden dance hall, left nearly unaltered for 85 years and locked off from the tenants of the Jefferson Arms. (Still, one long-gone former tenant once told me over a drink at lost Dapper Dan’s across the street that he had found the way into a “gold ballroom.”)

The old hotel’s biggest secret is the Gold Room, whose floor has rested from dancers’ feet for decades. The Gold Room is one of the vestiges of the Jefferson’s late Jazz Age remodel. Today, the lobby sports just a few traces of its 1928 look, including white marble staircases hiding out in the dark, unlit interior. The overlook was covered over after the 1950s, when the hotel briefly operated as a Sheraton. The public spaces read as cross between the would-be mid-century urban streamline and 1980s economical apartment styles. The marble stairs lead to the mezzanine level, where the grandest space in the Jefferson can be found, untouched by all of the modern changes that robbed the interior of complex beauty.

The Gold Room is a gently baroque artifact, with paneled and mirrored plaster walls, gold-painted accents, undulating balconies, and a ponderous crystal chandelier. Corinthian pilasters set against the walls provide a note of classicism to the space, but not one overtly staid. This room is a room set for fantastic happenings, not business luncheons. The Gold Room is also large: underneath its two-story ceiling, the room could accommodate as many as 1200 people, according to hotel brochures. Although the 1928 floor plan for the hotel has it labeled as a “Banquet Hall,” and it hosted many large dinners, the original design anticipated its use for dances — and the floor is a dance floor.

For almost four decades, the Gold Room served thousands of people through many large and lavish events. Debutantes came out annually at the Veiled Prophet Dinner in the Gold Room into the 1950s. Eventually, however, the Gold Room was shuttered to wait for a new era’s users. Planned renovation of the Hotel Jefferson by the Pyramid Companies — one of the building’s recent mysteries — came and went. The Gold Room will have to await new plans to return to its formerly busy social schedule. Meanwhile, inside of the dim interior of the Jefferson, the golden splendor of the hotel ballroom looks barely different than it did when the the city’s elite were celebrating the admiring gaze of the entire world.