Tim Logan has a good article on Urban Assets LLC in today’s St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

If only the daily paper had published a story like this when Blairmont Associates LC et al started buying…

Tim Logan has a good article on Urban Assets LLC in today’s St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

If only the daily paper had published a story like this when Blairmont Associates LC et al started buying…

by Michael R. Allen

Most in attendance agreed that while the NorthSide project was not ideal as proposed, it’s not too late to create a role for public input that will make changes. Some expressed the sentiment that the scale of the project will doom it, or that the plans as presented by Mark Johnson of Civitas was a smokescreen for a larger north side project or commercial development. People talked about the benefits of form based zoning, preservation review, incremental sale of city-owned property to guarantee development occurs in each zone, and the need to create mechanisms for removing existing residents and businesses from the authority granted to the developer. The ideas of private transit and power districts as well as property assessments worried many people who attended, who thought that those are already functions of government. There was discussion of development inequity between north St. Louis and the rest of the city, and how much north St. Louis needs the amount of investment that McEagle proposes.

The meeting concluded with discussion of the merits of crafting a form-based zoning code and a community benefits agreement (CBA) to ensure high-quality development and a contract between all stakeholders in the project. The idea of a CBA, which could be inclusive of the goals of diverse stakeholders (including McEagle), gained a lot of positive feedback.

A CBA an expansion of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch‘s idea of an advisory council for the project. It would also place all of the promises made by Paul J. McKee, Jr. and his team at the May 21 meeting into a real agreement between the developer and the project’s many stakeholders. On May 21, McKee listed promises that included saving buildings that can be saved, keeping existing residents in their homes, not moving a single job out of the area, including minority-owned businesses in the project and building urban and respecting the street grid. While the audience at City Affair was critical of some aspects of the project, by and large people expressed support for these promises — a critical starting point for consensus.

by Michael R. Allen

Hopmann Cornice is a family-owned business located at 2573 Benton Street in St. Louis Place, between Parnell and Jefferson. Hopmann Cornice has been manufacturing tin and copper cornices, gutters and downspouts since 1880, and has been housed in the larger building here since 1883 (the house to the west was subsumed into the operation later).

Hopmann Cornice is a family-owned business located at 2573 Benton Street in St. Louis Place, between Parnell and Jefferson. Hopmann Cornice has been manufacturing tin and copper cornices, gutters and downspouts since 1880, and has been housed in the larger building here since 1883 (the house to the west was subsumed into the operation later).

Hopmann is an inspiration — a company that has done the same thing for over 125 years, with few complaints from customers. Nowadays, a lot of Hopmann’s work is repair and replacement of historic cornices. Sometimes Hopmann ends up replicating and repairing its own historic work.

While Hopmann’s buildings aren’t historically perfect (note the metal siding covering the second floor as well as the boarded windows), the facility is serviceable, tidy and historically living. In many ways, the Hopmann buildings are more historically correct under continuous use than they would be with a fancy rehabilitation (which they do not require).

Of course, Hopmann’s buildings are far more likely to disappear than to be rehabilitated. Sensient to the west has bought out much of the land surrounding Hopmann for its large plant. Hopmann Cornice also is in the middle of McEagle’s NorthSide project, and more precisely is located in the southern end of one of the project’s planned industrial/commercial hubs. In fact, on the slide that McEagle showed at a meeting on May 21, this block of Benton Street is gone, and the Hopmann buildings along with it.

Hopmann’s building also appears on the TIF application for the project that McEagle submitted to the city last week. However, according to McEagle, that list contained some properties that they do not wish to purchase and they will resubmit the property list soon.

Perhaps McEagle has no use for the Hopmann Cornice land, and perhaps it won’t appear on the new list. Perhaps Hopmann Cornice will accept relocation. However, the project should defer to Hopmann and other long-time small businesses. These businesses are the existing job centers, generating work and city revenue. There is no need to displace good commercial stewards, and alderwomen April Ford-Griffin (D-5th) and Marlene Davis (D-19th) would do well to stand by these businesses. If they don’t want to be on the list of needed properties, they should not have to be. In the case of Hopmann, we have a business that is not only a stable long-time business but one that does unique and important work. If anything, McEagle may want to get Hopmann’s bids on the historic rehabilitation itemized in the sources and uses section of the TIF application. No one else will do the work quite like that!

Maria Altman, KWMU: “Future of pre-Civil War mansion rests with north side developer” (June 2)

Dale Singer, St. Louis Beacon: “Clemens mansion may find new life as museum, says developer McKee” (May 28)

On May 27, McEagle via Northside Regeneration LLC submitted its tax increment financing (TIF) application to the City of St. Louis. The requested amount of TIF is $410,000,000.

That application is online here.

by Michael R. Allen

Today Alderman Antonio French (D-21st) introduced Board Bill 78 to make his ward one of the preservation review districts governed by the city’s preservation ordinance. Preservation review allows the city’s Cultural Resources Office to review demolition permits in the ward and deny them based on the architectural merit and reuse potential criteria established by the ordinance.

The 21st ward is one of nine city wards that are not preservation review areas. Here is a map showing the distribution of wards that do not participate (in white):

This map shows that the area covered by the McEagle NorthSide project (mostly the 5th and 19th wards) is not included in preservation review. Neither is most of the north city swath in which Urban Assets and other holding companies are buying buildings and land.

A ward’s lack of preservation review enables demolition on a wide scale — not necessarily all at once, either. The conditions of many wards without preservation review have deteriorated through the loss of one building at a time for decades. Loss of buildings means loss of residents, loss of job and loss of a sense of community — adding up to conditions that make wards vulnerable for land-banking. Preservation review is not designed to keep every old building standing forever, but to create a mechanism for careful decision-making about the physical resources of our neighborhoods.

Alderman French has a great ward with a largely intact building stock. Placing the 21st ward under preservation review will help keep the 21st ward in good shape for generations to come. By making the move to place the ward under such review early in his tenure, French shows that he will be working to protect and strengthen the neighborhoods he already governs, rather than jockeying for the big development that can shatter communities.

Pay careful attention to these two slides. The first slide shows existing buildings in gray:

The second shows buildings proposed for preservation in black. Planner Mark Johnson at Civitas calls these buildings “legacy properties.” The three buildings at left (a house on St. Louis Avenue, Greater Bible Way Church and Crown Candy Kitchen), strangely, are not owned by McEagle. Crown Candy Kitchen is not even included in the project area. There was no discussion of preservation strategy beyond the promise that every building that could be saved would be saved.

McKee and Johnson both talked about how the warehouses between Delmar and Martin Luther King, including the GPX building, should be demolished because they wall downtown off from north St. Louis.

McKee and Johnson both talked about how the warehouses between Delmar and Martin Luther King, including the GPX building, should be demolished because they wall downtown off from north St. Louis.

More slides available online here.

This slide shows the possible phasing of “NorthSide, ” from A (first) to L (last). This slide shows that the first projects will be “employment centers” on the vacated 22nd Street ramps west of Union Station and at the head of the new Mississippi River Bridge. McEagle estimates that the project could take as long as 15 years to reach the final phase — a conservative estimate, in my opinion.

This slide shows ownership. McEagle holdings and proposed holdings (including currently-occupied homes and businesses and the Mullanphy Emigrant Home) are in purple, with public lands in blue. Paul J. McKee, Jr. promised that no property will be taken through eminent domain for any purpose other than creation of an employment center.

More slides available online here.

Reader Sara Collins shared with me her photographs of the slides shown by McEagle at last week’s public meeting at Central Baptist Church. I am sharing them to help readers who were not present get a better sense of the project scope.

This slide shows the ward boundaries and project outline:

This slide shows the proposed timeline for approval of tax increment financing and a redevelopment ordinance (a pretty fast track):

More slides available online here.

by Michael R. Allen

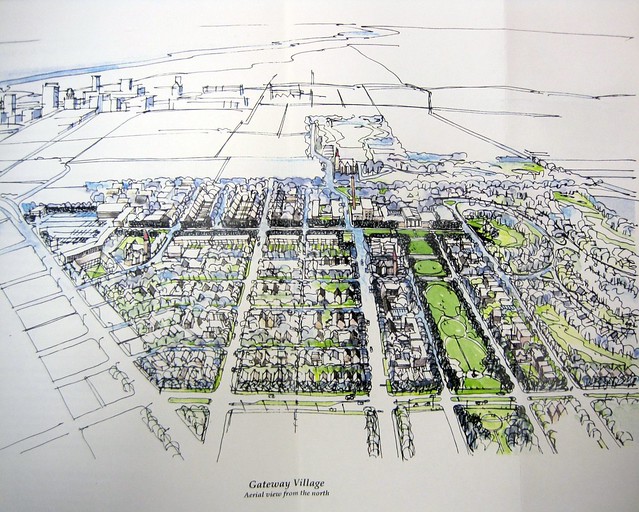

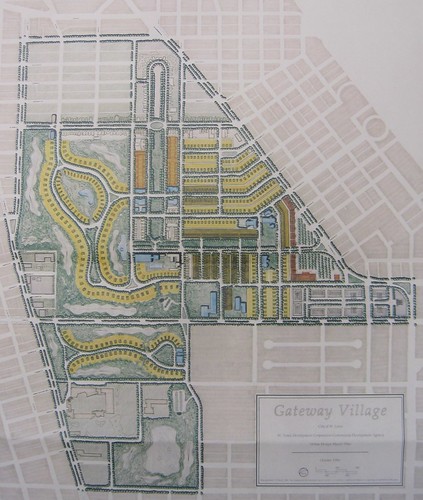

To some people, the current discussion about McEagle’s “NorthSide” project has roots in a project proposed for the same area 13 years ago: Gateway Village. Like “NorthSide,” Gateway Village involved a close relationship between a mayor and a private developer from outside of the city, proposed massive demolition, proposed eminent domain and large public subsidy. Unlike “NorthSide,” however, Gateway Village never moved close enough to reality to disrupt the section of St. Louis Place it would have wiped out.

In 1996, Mayor Freeman Bosley, Jr. unveiled his grand plan for revitalizing north St. Louis: a 180-acre golf course and subdivision called Gateway Village that would use the Pruitt-Igoe site as well as the western part of St. Louis Place. The boundaries were Martin Luther King Drive on the south, 20th Street on the east, St. Louis Avenue on the north and Jefferson Avenue on the west. The plan called for building 781 new homes (priced out of range of most St. Louis Place residents) and a 9-hole golf course (designed by renowned designers Don Childs Associates) platted for very low density at odds with surrounding historic city fabric. Going against neighborhood sentiment in an area where he had tremendous political support, Bosley supported the acquisition of 209 residences and six businesses to clear the project site.

The developer behind the project, whose identity was unveiled after the first announcement, was Waycor Corporation of Detroit. Waycor’s president was Don Barden, a wealthy Detroit businessman who has since gone on to become a major casino owner. At the time, Barden was the owner of television stations who had never developed a project on the scale of Gateway Village. Also in 1996, the Federal Election Commission determined that Barden has co-signed an illegal loan to a Detroit Congresswoman.

Whatever his inexperience and lack of ties to St. Louis, Barden gained the confidence of Bosley, Jr. and Maureen McAvey, the director of the St. Louis Development Corporation. Unlike today, where McEagle is unveiling its own plans, in 1996 Bosley and McAvoy did the public relations work for the developer. In August 1996, McAvoy released a study by Don Childs Associates that predicted that Gateway Village would be feasible and successful. The city paid the architects $38,000 for a study that championed a project in which they had a financial interest.

The study predicted that Gateway Village would precipitate “a return to living in major metropolitan cities” and that it would “act as a catalyst to revitalize the area.” The Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association, which is now defunct, rose up against the plan to safeguard the 209 homes sought for condemnation and demolition.

In October 1996, the city government requested a $8 million grant from the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development toward the project. The total project budget was $127.5 million, an amount fairly low for such a large area. The low cost was indicative of low density construction and low construction standards. Of course, $8 million was not the only handout sought by Waycor. Waycor wanted an additional $35 million in public financing. Waycor would not commit any of its own capital unless it could secure public money first — also different than the current situation.

The feasibility study commissioned by the city outlined the path toward development, with step one being “complete agreement with Waycor.” That step was removed after the St. Louis Post-Dispatch discovered that the city had commissioned a development feasibility study that not only recommended a certain developer but indicated that an agreement was already being created.

The Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association sent a letter to HUD Secretary Henry Cisneros asking that he deny the $8 million grant request. Shirley Booker was one of the authors of the letter and very active in organizing St. Louis Place residents. Vernon Betts was one of a few St. Louis Place residents who gave favorable comments about Gateway Village to the press, but the majority of residents were opposed.

Bosley’s response to the Greater Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Association’s letter is classic and timely: “It’s unfortunate that a small group now want to try and thwart the one thing that can work.” In development, there always seems to be “the one thing that can work” — what the person using that phrase wants to do.

An aldermanic election for the Fifth Ward, where the project was located, came in spring 1997. Veteran Alderwoman Mary Ross was retiring. In the race to succeed Ross, Democratic candidates April Ford-Griffin and Loretta Hall supported Gateway Village, and John Bratkowski was adamantly opposed. Ford-Griffin, whose support was for the project was not staunch, won the seat. At the mayoral level, Bosley lost the Democratic primary to Clarence Harmon.

Even before he took office, Harmon announced his plans to pull city government out of the Gateway Village project. On April 4, 1997, the Post-Dispatch published an article entitled “Harmon: ‘Dead Stop’ for Golf Course Plan,” that covered the mayor-elect’s opposition to a project that would lead to the dislocation of city residents. McAvey retorted that the project would bring the middle class back as well as retail for low-income residents.

Harmon’s move coincided with HUD’s denial of the city’s request for funding. Shirley Booker explained neighborhood opposition well. Residents wanted development, she said, “just not a golf course. We can’t keep existing with all this vacant land. The Lord didn’t mean for it to be like that. It’s a waste.”

McAvey clung to Gateway Village, though, telling the press that no one would be able to develop St. Louis Place without large public subsidy and amenities provided. Her tenure would end shortly thereafter. Ford-Griffin learned a few lessons from Gateway Village and spearheaded an often rocky but productive community-based planning process leading to the Fifth Ward Master Plan, published in 2000 although not fully adopted by the Board of Aldermen.

Harmon, of course, showed little leadership on development issues, but his decision to pull the plug on Gateway Village allowed for the kindling of small-scale development on the near north side. Many leaders, however, continued to bemoan the lack of a large scale plan for the area around Pruitt Igoe. Bosley, Jr. himself is now a backer of the McEagle project, seen occasionally accompanying Paul J. McKee, Jr. at meetings.

One of the problems with the Gateway Village debacle and the resulting Fifth Ward Master Plan is that there was no strong legislative result. The threat of a large-scale plan in the Fifth Ward remained because there were no basic protections against that mode of development. Zoning and land use recommendations were never implemented as law, historic districts and sites were not identified and listed in the National Register of Historic Places, and redevelopment zones that would have broken the ward into smaller pieces were not created. The Fifth Ward’s biggest problem in recent years is the large amount of vacant city-owned land — quite a big prize to lure developers. Without safeguards against large scale projects, the ward has been left vulnerable to the supersized visions that Gateway Village illustrated.