by Rick Rosen

Over the course of a century a community took shape on the riverfront in St. Louis. At the same time, what happened in that community shaped the history of the nation. Finally, as those years of destiny unfolded, St. Louis came to see itself as a capital, as the great center of the Midwest.

But then, the currents of history changed. The river of history shifted its course and bypassed that community. Chicago, not St. Louis, became the capital of the Midwest.

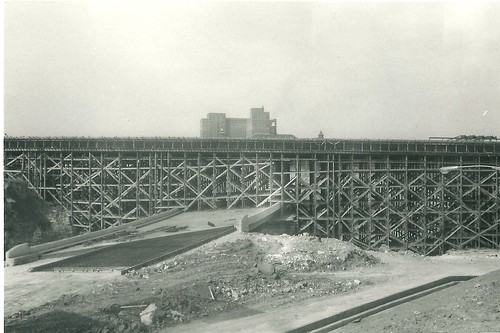

Ever so gradually, the riverfront was forgotten. Then it decayed. Finally, it became an embarrassment to the still thriving but less influential community that had grown up around it following its century of greatness.

In that larger community, the humiliation of having lost out to Chicago lingered on. The embarrassment ran deep and it was accompanied by amnesia — a defense mechanism to cope with humiliation. The amnesia masqueraded as conventional wisdom: the riverfront is economically obsolete with regard to its building stock; the riverfront is obsolete in relation to advances in transportation technology; the riverfront is out of date in comparison to current styles of architecture.

All this conventional wisdom was, of course, true. However, it took hold not because it was true, but because it addressed a psychic need to mask the profound sense of loss that ate at the community’s identity, a loss for which the decaying riverfront was a constant reminder.

And then the great depression arrived. Luther Ely Smith, a man of great vision and a respected leader in his deeply embarrassed community, remembered that first century of greatness — and was appalled by its decadent reflection in the mirror of the nearly abandoned riverfront. He dreamed of something to replace the decadence, something that would bring back to life that lost century of greatness. Smith prevailed on the federal government — in response to the depression—to build a national park on the riverfront. Then he organized a design competition to create a new vision for the site.

And of course he succeeded — beyond his wildest dreams — with the Gateway Arch and its surrounding park grounds. But there was a cost.

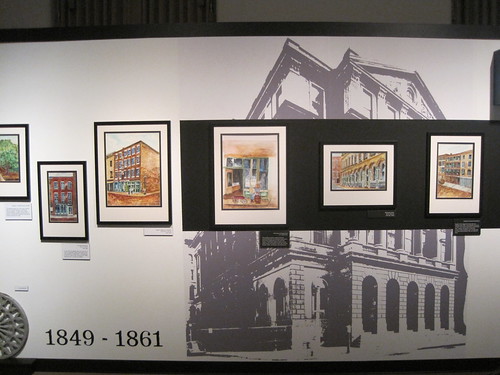

A city’s built environment is nothing less than the accretion of its history. Whenever elements of that environment are wiped away, the material record of that history is lost. When the riverfront was cleared after 1939, the elements that were lost were the very elements Luther Ely Smith sought so hard to recover.

Any built environment tells the story of its history. But it’s also true that it tells that story in a special language, an arcane language that only people who are drawn to history, and those whose personal memories are embedded in its buildings, can easily understand. Still, despite its weaknesses, it is by far the best language for telling a community’s story. When it’s silenced, other languages must be found if the story is to be remembered at all.

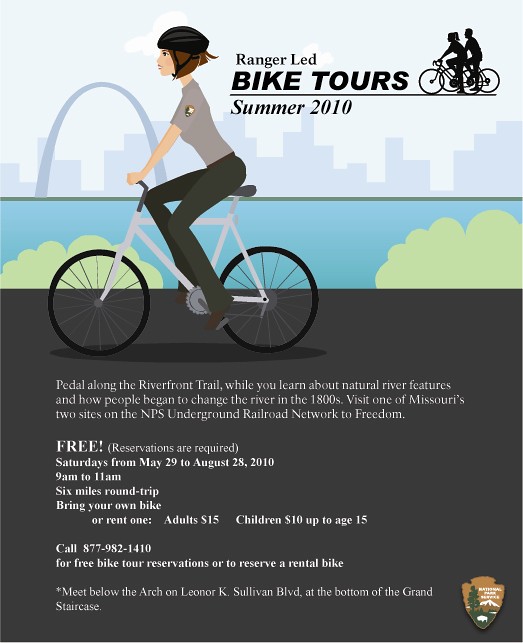

Today, a second design competition for the riverfront is in progress. This competition presents a magnificent opportunity for St. Louis and it has already generated widespread excitement. Most of the excitement focuses on possibilities for new connections between the arch grounds and the rest of the city. However, with the original built environment of the riverfront long since gone and forgotten, the hidden challenge of the competition is to find the next best language to tell that lost story. Then, and only then, can the amnesia that has prevailed for so long in St. Louis finally be healed.

Rick Rosen is an architectural historian and downtown resident. Contact him at RARstl2@aol.com.