by Michael R. Allen

Somehow, some way, the poor old Mae Building still stands at 4468 Delmar Boulevard on the north edge of the Central West End. Last May, a speeding car crashed into the northwest corner of the building, knocking a section of the corner wall at the first story away and forcing building tenant the Williams Ornamental Iron Works to relocate. After the accident, the Building Division condemned the Mae Building for demolition on May 21, 2007, but neither the division nor the building owner has acted to demolish or repair the building. Scarcely a brick has moved in that time, too, which testifies to the solid construction. Still, in the present condition, the fate of the building seems certain.

Somehow, some way, the poor old Mae Building still stands at 4468 Delmar Boulevard on the north edge of the Central West End. Last May, a speeding car crashed into the northwest corner of the building, knocking a section of the corner wall at the first story away and forcing building tenant the Williams Ornamental Iron Works to relocate. After the accident, the Building Division condemned the Mae Building for demolition on May 21, 2007, but neither the division nor the building owner has acted to demolish or repair the building. Scarcely a brick has moved in that time, too, which testifies to the solid construction. Still, in the present condition, the fate of the building seems certain.

The Mae Building is part of a row of two-story commercial buildings that once gave this side of this block of Delmar great definition. Gradually, much of Delmar between Union on the west and Vandeventer on the east has slipped away. Buildings like these two-story commercial storefronts are rare nowadays, although many sites are now occupied by infill residential construction. The 4400 and 4500 blocks around the intersection of Delmar and Taylor has yet to see great infill or rehabilitation. Instead, just a few blocks from the vibrant heart of the Central West End, this intersection continues to shed its architectural resources. While the southeast corner of the intersection retains a two-story building with a rounded, projecting corner bay (once a turret base), between that building and the Mae Building is a wide unkempt vacant lot. On that site stood the commercial buildings at 4470 and 4474 Delmar, demolished in 2005 and documented on this website.

All of the buildings lost here have been of a high quality of detail, befitting the prominence of the thoroughfare. Still, the Mae Building’s history shows a different course than the others — it was refaced with the present facade. The building actually was built in 1889 as a two-story commercial building housing a string of blacksmith shops in the first floor. In fact, a fairly saturated ghost sign remains on the western elevation, spelling out “[H]ORSE SHOER.” Apparently, there was no two-story building next door in 1889.

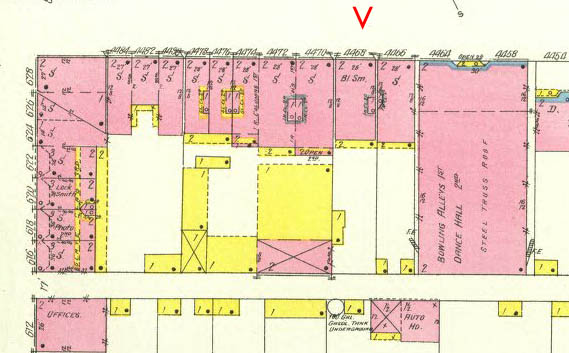

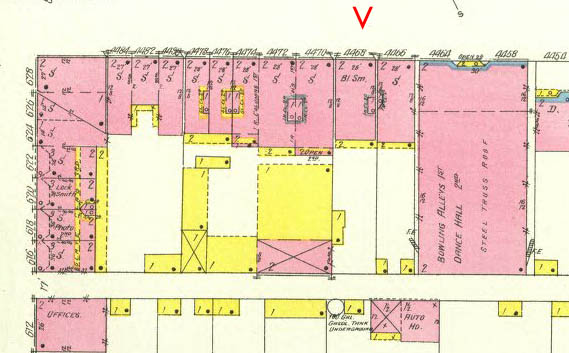

The 1909 Sanborn map, however, shows a densely filled-out block face. (Above, the Mae Building is marked by a red carrot.) Two-story commercial buildings line the 4400 block of Delmar, and on this side of the street stretch east from Taylor to mid-block, where a large dance hall and bowling alley abruptly abuts the row of residences that fill out the remainder of the street face.

The 1909 Sanborn map, however, shows a densely filled-out block face. (Above, the Mae Building is marked by a red carrot.) Two-story commercial buildings line the 4400 block of Delmar, and on this side of the street stretch east from Taylor to mid-block, where a large dance hall and bowling alley abruptly abuts the row of residences that fill out the remainder of the street face.

By 1917, city directories show the Mae Building occupied by Delmar-Taylor Ford Specialty Auto Repair. Metal and transportation are still the mainstays of the building’s commerce, but in a much more modern fashion. This use finds an ironic dovetail with the repairs required to the building inflicted by an automobile. The Ford repair shop survived until September 29, 1927, when a devastating tornado cut through the neighborhood and severely damaged the face of what would become the Mae Building.

Like most, the owners rebuilt the building. Judging from the side walls, neighboring buildings held the sides solid, so the front must have took the force of the damage. (Eighty years later, without the protection of adjoining buildings, the impact of a mere automobile may have been fatal.) The new front elevation was modern without being daring — a design taking Arts & Crafts and Tudor Revival influences prevalent at the time. White vitreous brick covered most of the wall, interrupted by jazzy green courses of the same material and more somber terra cotta pieces. A polychromatic shield was placed at the center of the parapet, proclaiming the building’s endurance. I have no idea what the building looked like before the tornado repairs, but afterwards it was fancy for an automobile repair shop. Entrance to the service bay was elegantly kept at the rear.

The 1929 city directory lists C.W. Quint Automobile Repair occupying the first floor, with an apartment above. (Did Mae live there? Not sure.) Automobile repair was the primary use for over fifty years. Eventually, the building fell on the inventory of the Land Reutilization Authority, but Royal Vaughn bought it in 1998 and the Williams shop moved in afterwards, maintaining the building’s connection to metal work. Telling that a building that survived the 1927 tornado had no trouble surviving the LRA!

Cut back to the present, and the story of the building at 4468 Delmar faces an unpredictable ending. Wise guys foretell demolition, while dreamers hold out hope that the corner will be rebuilt and the building remains. In a twist of fate, the building itself inadvertently offers us the best answer to the question “Will the building survive?”

I have taken so many photographs of north St. Louis buildings that I often fall behind in tracking the subjects. The buildings shown above are a good example, since this photograph dates to August 2005, their demolition took place in 2006 and I noticed their loss in 2008.

I have taken so many photographs of north St. Louis buildings that I often fall behind in tracking the subjects. The buildings shown above are a good example, since this photograph dates to August 2005, their demolition took place in 2006 and I noticed their loss in 2008. The otherwise plain house stood out with the addition of that striking but basic architectural form. Next door, the flats at 4405 Evans use the turret in a different way.

The otherwise plain house stood out with the addition of that striking but basic architectural form. Next door, the flats at 4405 Evans use the turret in a different way. Brick quoins and terra cotta panels adorned the Classical Revival building, but that center-placed turret was the crown. Rising above the flared gable’s peak, the turret drew the eye toward the sky, balancing the view of the building with a strong sense of the natural world around it. The architect’s skyward aspirations were immodest but also inspiring. Here, as in so many other instances in St. Louis, a building for the common person was addressing the street with architectural finery and any power above with a tall turret.

Brick quoins and terra cotta panels adorned the Classical Revival building, but that center-placed turret was the crown. Rising above the flared gable’s peak, the turret drew the eye toward the sky, balancing the view of the building with a strong sense of the natural world around it. The architect’s skyward aspirations were immodest but also inspiring. Here, as in so many other instances in St. Louis, a building for the common person was addressing the street with architectural finery and any power above with a tall turret.