by Michael R. Allen

Amid a heat wave and the pop-pop of homegrown independence celebration came an easy-to-overlook but significant preservation victory: the St. Louis Circuit Court’s affirmation of the Preservation Board’s decision to block demolition of the warehouse at the Cupples Station complex known colloquially as “Cupples 7.” Upon appeal by owner Kevin McGowan’s company, the Preservation Board upheld the Cultural Resources Office denial of a demolition permit at its meeting on November 28, 2011. McGowan appealed the decision to the Planning Commission, which voted to take no action.

Under the city’s preservation ordinance, the final appeal is to the Circuit Court. McGowan followed in the footsteps of legendary developer Larry Deutsch, who in 1995 famously obtained a Circuit Court ruling overturning the predecessor Heritage and Urban Design Commission’s denial of demolition of the former Miss Hullings Building at 11th and Locust Streets. McGowan’s Ballpark Lofts III LLC joined creditor Montgomery Bank in a suit against the city in Circuit Court seeking demolition as well as inverse condemnation. On Friday last week, McGowan lost on both counts.

The Circuit Court ruling affirms all of the Cultural Resources Office and Preservation Board findings, yet it concedes that the point of Cupple 7’s soundness under the definition of the preservation ordinance “presents the Court with its most difficult assessment of the evidence.” Yet the Court disagrees with the conclusions submitted by McGowan’s structural engineer. Most importantly, the Court ruling finds that McGowan failed to explore temporary structural stabilization of the building — a point that preservationists brought up at the Preservation Board meeting.

Perhaps the most significant part of the ruling is its dismissal of claims made by McGowan attorney Jerry Altman that structural stabilization of Cupples 7 would cost $7-8 million and full rehabilitation would cost about $52 million. The Court’s response is summed up as “prove it” — the Court finds that McGowan submitted no independent analysis to prove these figures had any basis. Likewise, the Court dismissed Altman’s assertions about the loss should McGowan’s company sell the building for less than its mortgage of $1.4 million. Again, no evidence.

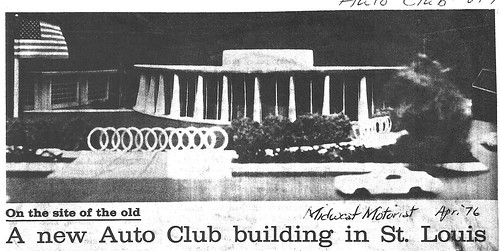

The Circuit Court ruling on Cupples 7 affirms the strength of the city’s preservation ordinance, and the need for Preservation Board decisions to be considered on the basis of fact. On the surface, this seems to be a very simple ruling. Yet its timing makes it very important. Besides McGowan, recent demolition seekers at Preservation Board meetings, like the AAA, have brought forth claims about architectural merit and reuse potential that lack legal, financial or professional base. The Cupples 7 ruling reminds everyone that those arguments don’t hold any legal weight, and that the Preservation Board should continue to stick to the facts.