by Michael R. Allen

This is the fifth part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

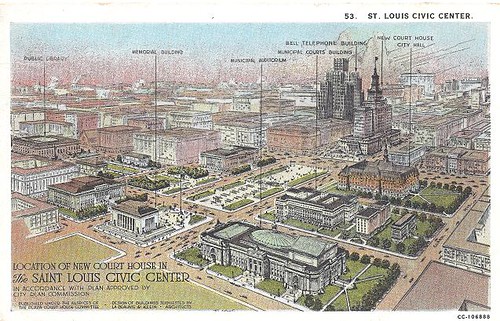

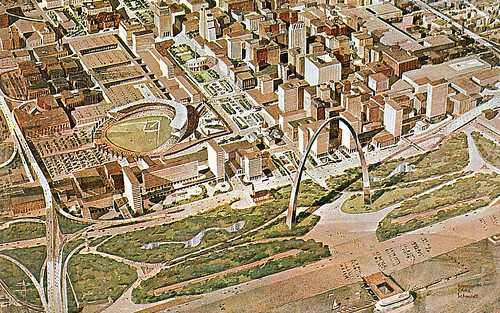

Selection of Eero Saarinen and Dan Kiley’s plan for the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial design in the 1948 design competition drew planners’ attention to eastern downtown. In 1954, the architectural firm Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen published a rendering of an eastern park mall running from the Civil Courts and terminating at the new Memorial. The block between Third (now Memorial Drive) and Fourth Streets would be landscaped by the National Park Service as part of the Memorial and named Luther Ely Smith Square. The firm’s rendering was the first time that the idea of extending the downtown park system to the east had been considered.

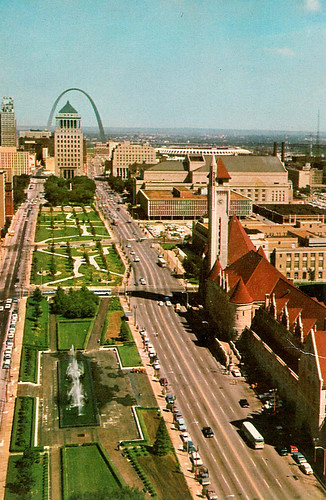

The rendering by Russell, Mullgardt, Schwarz & Van Hoefen coincided with creation of the western blocks between Fifteenth and Eighteenth streets between 1954 and 1960. Those blocks joined existing Memorial and Aloe plaza blocks to form a mall-like line of parks from Twelfth Street (later Tucker Boulevard) west to Twentieth streets. The new Jefferson National Expansion Memorial and Luther Ely Smith Square shaped an eastern terminus for the larger park project that would soon be named the Gateway Mall.

Yet the Civil Courts Building and the Old Courthouse were obstacles to a continuous park mall. Still, the rendering of formally symmetrical park space joining the existing Memorial Plaza and park mall at the west to the Memorial at the east was immediately popular. Anticipating timely completion of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, downtown business leaders wanted to reconstruct eastern downtown with a modern built environment worthy of a major international landscape.