by Michael R. Allen

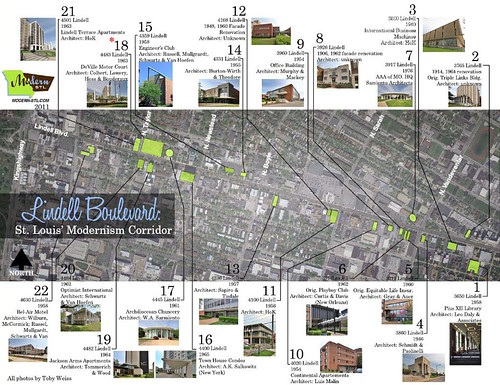

For years Toby Weiss and I have been giving tours of and writing about the unique concentration of mid-century modernism on Lindell Boulevard between Grand and Kingshighway. This significant concentration of modernism has sustained some losses and currently is enduring threats to both the IBM Building (1959, Hellmuth Obata & Kassabaum) and the AAA Building (1976, W.A. Sarmiento). However it remains the city’s strongest collection of non-residential mid-century modern design.

Modern STL, on whose board both Toby and I serve, has now published a beautiful two-page self guided tour of Lindell Boulevard that includes information about each of the street’s mid-century modern buildings as well as a brief essay that I wrote providing an overview of modernism on Lindell. Modern STL board member Neil Chace generously donated his talent to design the guide. Download it here and then go for a lovely walk down Lindell!