by Michael R. Allen

The notion of buildings that speak helps us to place at the very centre of our architectural conundrums the questions of the values we want to live by – rather than merely of how we want things to look.

– Alan de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness

In 1956, two small one-story buildings were completed around the downtown area. One was designed by a renowned modernist designer for a growing financial institution, while the other was a modest building built by a family-owned business. Yet both buildings were modern in style, and, more importantly, built amid rapid and often conflict-laden demographic changes around the city’s commercial core. These commercial outposts would become most significant for association with the city’s struggles for racial and social equality. Today these two buildings speak of the contradictions inherent in mid-century modernism: the remaining beauty of design and the unacknowledged backdrops of overt racism and economic strife.

Yet neither building sports a plaque, and one most likely will be demolished. Both are keys to showing the story of the city’s social justice struggles in the recent past. While businessmen perched at desks in modern office towers downtown, and families enjoyed sunlight from large banks of windows in their latest Eichleresque ranch in St. Louis County, thousands of St. Louisans fought for the same opportunities. Modernist architecture sometimes was the backdrop there as well, as two very different buildings show.

The Jefferson Bank and Trust Company Building: W.A. Sarmiento Meets CORE

Earlier this year, the Cultural Resources Office kicked off the citywide St. Louis Modern architectural survey (conducted with assistance from Portland-based Peter Meijer Architect PC and modernista Christine Madrid French) by publishing an image of the Jefferson Bank and Trust Company building at the southwest corner of Jefferson and Market streets. The architectural symbolism was double: the building is both the work of one of St. Louis’ most important modernist commercial designers and the site of one of the city’s most significant (and complicated) civil rights demonstrations. That the project would be visually marked by a building connected to both aesthetics and social unrest bodes well for future local scholarship in modern architecture.

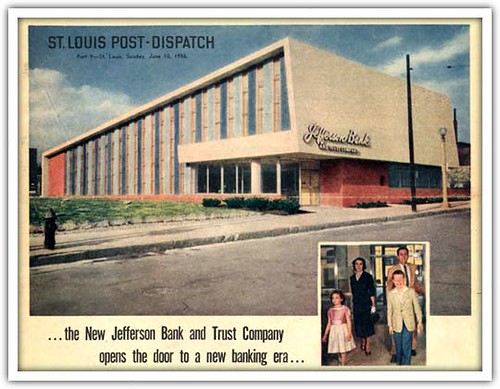

The striking modernist bank building is the work of celebrated architect W.A. Sarmiento, in his capacity as chief designer for Bank Building and Equipment Corporation of America, and was completed in 1956. The building was the second home of a bank that started on a site three blocks north and moved to its present home on Market Street in 1977. When the new bank opened on April 2, 1956, the press reported that it was the first new bank building in the city completed since 1928. The unknown veracity of that claim does not diminish the fact that Sarmiento’s hand places the building among the region’s finest modernist works.

Wenceslao A. Sarmiento, born in Peru, started designing for the prolific Bank Building and Equipment Corporation of America in 1949. By 1952, Sarmiento was chief of design and had reoriented the company’s design practice toward a brand of iconic, playful modernism that drew inspiration from work by Frank Lloyd Wright, Oscar Niemeyer, Harris Armstrong and other less-than-doctrinaire designers. Sarmiento eschewed the functionalist conventions of the International Style, and even introduced ornament to his designs through lettering, grilles and other elements. Sarmiento is a peer to Edward Durrell Stone and others nationwide breaking from academic modernism. In St. Louis, Sarmiento’s work includes the IBEW Local #1 Headquarters (1960), the Chancery of the Archdiocese (1963) and the AAA Building (1976, designed through his subsequent solo firm).

Ahead of the contract for the Jefferson Bank and Trust Company building, the Bank Building and Equipment Corporation felt the pains of the postwar building economy. Remodeling projects outnumbered new buildings ten to one in 1952. However by 1956 the firm had 35 new projects, including substantial new construction projects. These trends reflect trends across St. Louis in which postwar modernism’s first major commercial wave consisted largely of remodeling and recladding projects.

For the Jefferson Bank and Trust Company building (incidentally built after demolition of the St. Louis Coliseum of 1908 designed by Frederick C. Bonsack), Sarmiento conjured a planar sonata of sorts. The main entrance, now bricked in, was located at the corner under a prominent sloped wall plane that joined a dramatic back-sloped roof plane over the office areas. This was offset with a roof plan of diverging slopes on the west side of the building, where the lobby was located. As prominent as the pronounced roof forms were the eight drive-up banking windows underneath projecting flat roofs. The building’s materials bridged the gap between resolute modernism and local building culture: local red brick, metal and stucco. The price of construction was reported at $650,000.

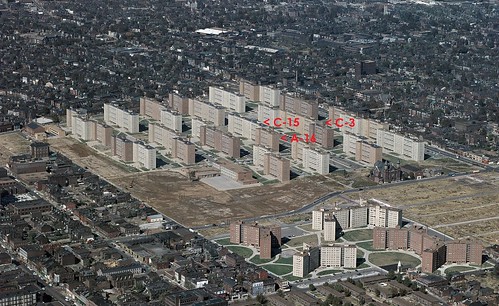

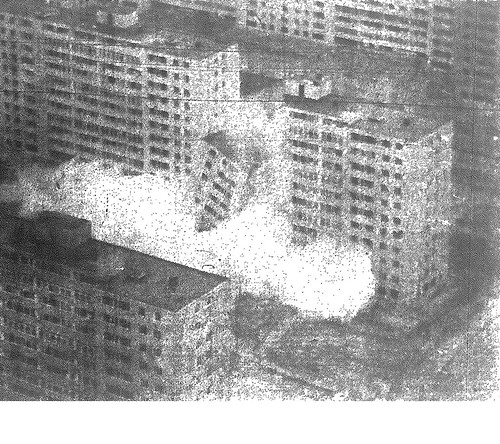

Implanted in a space age building, Jefferson Bank and Trust Company’s assets grew future-forward, from $22 million in 1955 to $52 million in 1963. The context for the building changed greatly as well. The city cleared the 97 block Mill Creek Valley district to the south starting in 1959, changing the entire context of the area from a historic African-American neighborhood to a monumental corporate and institutional park. The massive Pruitt-Igoe housing project had opened to the north in 1956, fostering changes in surrounding blocks. All of a sudden, Jefferson Bank and Trust Company was central to the storms of struggle and radical urban surgery. The corner of Washington and Jefferson was no longer a placid spot for business, but ripe with potent unrest as palpable as the lines with which Sarmiento endowed the building.

In 1963, the Congress for Racial Equality (CORE) led demonstrations against Jefferson Bank and Trust Company over the bank’s dismal record in hiring and promoting African-Americans to professional positions. While other banks were equally complicit in these patterns, Jefferson Bank and Trust Company stood in a historically black neighborhood and held state and city funds (including public employee pension funds). CORE’s leaders thought that pressure on the bank could lead to withdrawal of public funds.

CORE demonstrations in summer 1963 quickly led to an injunction from the St. Louis Circuit Court. On August 30, 1963, 250 demonstrators gathered and marched into the bank singing “We Shall Not Be Moved” and “We Shall Overcome” in defiance of the court order. Nine demonstrators, including future Congressman William L. Clay, Marion Oldham, Norman Seay and others, were arrested and late sentenced to jail time. Other demonstrators were arrested on October 4 and 7 following more demonstrations. The demonstrations raised public awareness of racist bank practices, but failed to achieve the result of getting the city to remove funds or immediate bank changes. Many people served jail terms, and activists became divided over the tactics and strategy used.

The outcome of CORE’s efforts galvanized more radical young activists who widely viewed the failed demonstrations as the result of timid traditional activism. New paths were forged in the wake of the Jefferson Bank and Trust Company demonstrations. Percy Green II denounced the “battle fatigue” of older CORE leaders and founded the Action Committee to Increase Opportunities for Negroes (ACTION) in 1965. Green soon after would shake up the city by attempting to scale another modernist landmark, Eero Saarinen’s Gateway Arch. That iconic work of architecture bears the scars of inequality in construction job hiring, the target of Green’s protest.

The lack of an identifying marker or official City Landmark status for the Jefferson Bank building is unfortunate. Then again, in the entire Mill Creek Valley neighborhood to the south not a single marker stands to commemorate the African-American experiences there. Only on Locust Street is there a sidewalk plaque, marking the childhood home of poet T.S. Eliot. The refusal to acknowledge these African-American history sites brings to mind the words of Norman Seay when interviewed in 2010 about the Jefferson Bank protest.

When in 2010 St. Louis Beacon writer Linda Lockhart asked if racism was still alive in St. Louis, Seay said yes — with a sobering qualification: “It’s sneaky. It’s subtle.” Interest in preserving modernist architecture in St. Louis and elsewhere has largely deflected the messy strands of design and race. Urban renewal and its landscapes are largely panned by preservationists, and the social injustice decried. Yet modern architecture’s complexities extend far beyond obviously contested sites. Struggle is as worthy of commemoration as is exemplary design — because both are integral components of the architectural battleground of postwar St. Louis.

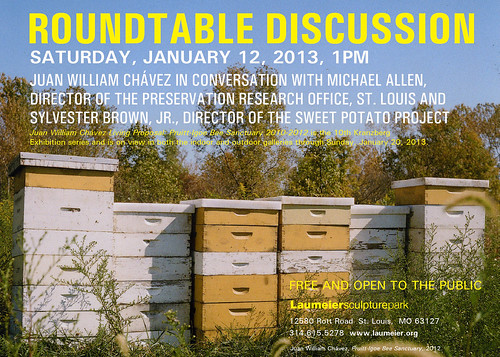

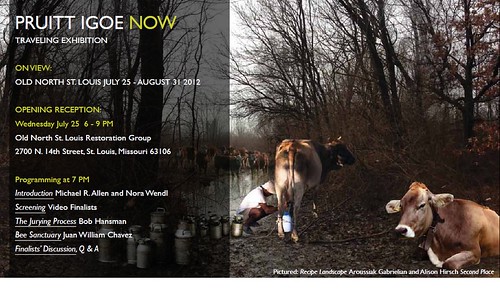

The Pruitt Igoe Neighborhood Station: A Modest Monument

Across Cass Avenue from the forest marking the Pruitt-Igoe housing project, at 2411 Cass Avenue stands a little building with a sun-catching tapestry of modern brick on its front wall, and plain concrete blocks on its sides and back. The Richardson family built the building in 1956 and opened a delicatessen that no doubt benefited from the arrival of some 12,000 residents at the brand new public housing complex. Yet the little building would play a more significant role in the life of Pruitt-Igoe, albeit briefly.

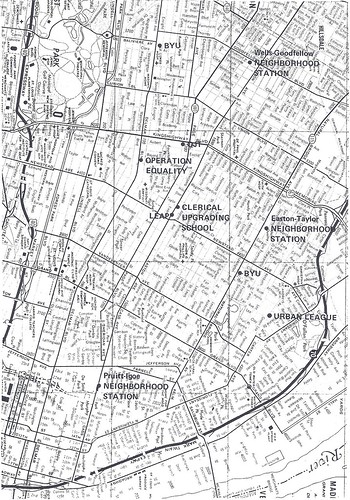

The Urban League of St. Louis assumed operation of St. Louis’ anti-poverty program in September 1965. With funding coming through the Human Development Corporation, the Urban League opened four “neighborhood stations” to serve districts in north St. Louis identified as having high concentrations of poverty. These districts were Wells-Goodfellow, Easton-Taylor, Yeatman and Pruitt-Igoe. Today, with the exception of the mostly-cleared Pruitt-Igoe district, the areas are still among the city’s poorest and most in need of social services.

The Urban League leased the Richardson delicatessen from 1966 through 1969. During those years, the building was the Pruitt-Igoe Neighborhood Station. There, the Urban League offered an array of services including job training and placement, sex education, tutorial programs, Head Start and health classes. By 1965, Pruitt-Igoe’s woes were dire. The 33 towers already had a vacancy rate of more than 25%, and the remaining residents were nearly all African-American and among the city’s poorest. Still, residents had moxie. The people who used the Pruitt-Igoe Neighborhood Station established an advisory committee and helped the Urban League reach more residents and find private resources not included in the anti-poverty program’s annual public grant.

Panacea for Pruitt-Igoe’s ills was not even remotely possible, but stopgaps were. In the little brick-faced building on Cass Avenue, the Urban League tried to help residents do the best that they could – with limited funding and limited resources. In the end, the Neighborhood Station was not enough, and when it closed drastic measures were in the works for Pruitt-Igoe. The Model Cities program went into effect nationwide, and the city of St. Louis chose a big part of north city including Pruitt-Igoe for federal funds that — had they been sufficient and steady enough – might have cleared and reshaped the area. Model Cities briefly assumed the Cass Avenue building as an office.

Where planners next dreamed of utopian solutions to address the dystopian realities of north city, today one will find no traces. Today, the little building is owned by Northside Regeneration LLC, which purchased it after it had long gone vacant. The four walls are strong, but the roof structure forms a wooden mess inside. Paired with the adjacent Grace Baptist church, founded by Pruitt-Igoe residents and utilizing a former neighborhood grocery store, the Neighborhood Station building is a key fragment of St. Louis’ housing crisis. I am not the first to state that the small building would make a fine Pruitt-Igoe museum. At the least, it stands silently testifying to the social realities of modernism.

To understand mid-century St. Louis, we must peel off our filters that privilege high-style modernism and the lives of the middle and upper classes. Our Sarmiento-designed landmarks lose a lot of context without the backdrop of Pruitt-Igoe and homegrown modern buildings like the Richardson deli. The vagaries of time, use and memory dispel any notion that we can save all. Yet as we evaluate what parts of architectural epochs are worth keeping, let us not forget sites of struggle and sites built through poverty. Until the city has vanquished racial and economic barriers, these landmarks tell us as much about ourselves as do the valuable, colorful and sophisticated modernism seen in designs that include Jefferson Bank.