by Michael R. Allen

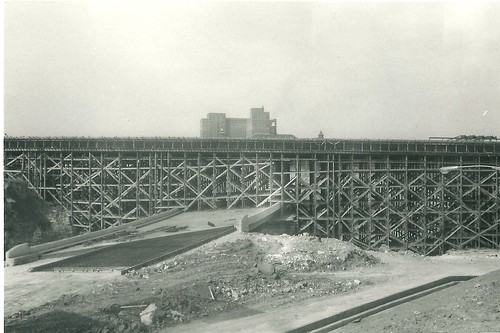

These two photographs from our collection show two eastward views from the late 1940s down Cherokee Street around Christmas time. Amid the wreaths decorating street lights are an array of shoppers and so many projecting store signs that a count seems impossible. These photographs really make clear how much signs and marquees are visually interesting and worthy parts of the historic built environment, unfortunately now discouraged or effectively outlawed in commercial districts by zoning and local historic district ordinances. (Apparently turning on a stopped historic clock on Cherokee Street is even controversial to the city government, despite the clock’s clear role in the physical fabric.) An exact date for these two photographs, taken on the same roll of film, has not been determined but visual information likely set the year between 1945 and 1950.

Also present is the tension between modes of transportation. The streetcar, whose sign reads “Jefferson Line” in the photograph above, is dominant in the center of the street, but parked automobiles outnumber the streetcars and their rider capacity. Soon they would be the only motor vehicles on Cherokee Street.

Above, we see the Casa Loma Ballroom at left in its present appearance, which dates to reconstruction following a fire in 1940. The Dau Furniture Company marquee at left projects from a lavishly-detailed terra cotta front on the building at 2720 Cherokee (1926, Wedemeyer & Nelson). To its right is part of the former Cherokee Brewery. Almost every building in this scene still remains.

To the east at Ohio Avenue, the view is even more abundant with blade signs touting various stores and companies on Cherokee Street. The northeast corner building, now home to Los Caminos gallery, was the the home of the South Side Journal. Frank X. Bick founded the newspaper in 1932, and it is now part of the Suburban Journals with an office in West County. Other signs include those for Fairchild’s and Stone Bros. attached the a now-vacant building once operated by Anheuser-Busch as the Kaiserhoff, and one in the far background for Ziegenhein Bros. Livery & Undertaking Company. Visible diagonally across the street from Ziegehein Bros.’ building is the sign of 905 Liquors, housed at Cherokee and Texas in what became the home of Globe Drugs. At the time this photograph was taken, murals by artist J.B. Turnbull adorned the walls of that particular location of 905.