by Michael R. Allen

In St. Louis, the city’s preservation ordinance creates review of demolition permits on architectural and historic merits only in designated districts. These districts are designated by aldermen and generally follow ward boundaries, although with redistricting and the coming ward reduction these boundaries increasingly make little sense. While the review system established by ordinance is professional, and professionals review the demolition permits, the creation of review boundaries has been political since the city revamped the preservation ordinance in 1999. The politics of review have actually led to increased coverage of demolition review, however, but some areas seem perpetually left out.

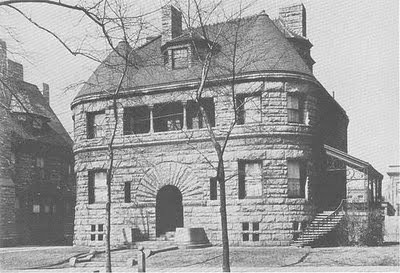

In one of the wards in which does not have review, the 19th Ward, stands the Charles H. Duncker Residence — at least for another few weeks before the stone castle falls forever into a grassy abyss. Alas, the stately former dwelling has neither a City Landmark nor a National Register of Historic Places listing, both of which would have placed its demolition under review. (Ever-vigilant Paul Hohmann already alerted us to the demolition in Vanishing STL; then he took excellent interior photographs.)

Located at 3636 Page Boulevard, the Duncker Residence has a storied life that draws heavy in arenas of our past that affect almost all of us. First, the house was built by a distinguished German-American capitalist, who elected to build a French Renaissance Revival design in league with City Hall and other landmarks. Then, upon the original owner’s departure to tranquil Clayton, the house had new life as the Jewish Community Center. Finally, as the Jewish community’s geographic center left, the house became a celebrated African-American retirement home. Today, much of the house is rubble.

The Charles H. Duncker Residence and the French Renaissance Revival Style in St. Louis

The Charles H. Duncker Residence and its carriage house was built at a time of stylistic transition in the high-style residential architecture of the city. The house’s stylistic traits would straddle somewhat the waning Romanesque Revival and short-lived French Renaissance Revival styles, showing the eclectic tendencies of 1890s St. Louis. The house was built toward the end of the 19th century’s last decades; the city issued a building permit to Charles H. Duncker on December 3, 1896. According to the permit, the construction cost was $15,000. The St. Louis Daily Record provides a scant clue as to the designer of the house: “contract to be sublet” is listed under “architect.”

The Duncker Residence was built as a two story house with attic story tucked under a high-pitched hipped roof. Rough-faced ashlar limestone cladding, a wrap-around porch with stone columns of the Ionic order, a short front and west side turreted bows with low dormer and a full-height three-story eastern turreted side bow were defining characteristics of the large dwelling. The preponderant orientation of the house is toward the French Renaissance Revival style, although the prominent turreted bows suggest Romanesque Revival influences and recall buildings like Link & Cameron’s Union Station (1894) or H.H. Richardson’s John Lionberger House (1888). Yet the square-headed windows, recessed entrance columns with Ionic capitals and high-pitched roof are all elements associated with the French Renaissance Revival.

The French Renaissance Revival style employed traits of the Romanesque Revival: tall roofs often with dormers, bows or turrets, large stone elements and picturesque massing. However, the French Renaissance Revival drew upon ornamental elements that were classically oriented, breaking from the austerity of H.H. Richardson’s forms. The French Renaissance Revival style popularized in St. Louis upon the winning submission in the City Hall design competition was Eckel & Mann’s plan, drawn by Harvey Ellis, based on the Hotel de Ville in Paris. St. Louis City Hall (1898) joined Barnett, Haynes & Barnett’s Visitation Academy (1892, demolished) and Ellis’ St. Vincent’s Sanitarium (1894) in Normandy as a prominent exemplar of the style.

By the late 1890s, St. Louis’ wealthy families were choosing a wide range of styles. The completion of the John L. Davis Residence on 1893 (Peabody, Stearns & Furber) brought the Italian Renaissance style into prominence, and broke a streak of Romanesque Revival popularity. The French Renaissance Revival allowed for a gentle transition between the heavier Roman forms and the more ornate appearances coming into vogue.

Around the Midtown and Vandeventer area are several works that compare to the Duncker Residence. The last building at Fout Place, located very close by at Cook and Whittier, dates to 1892 and offers a more pronounced Romanesque influence. However, the massing and main entrance are very similar. The Robert Henry Stockton House at 3508 Samuel Shepard Drive, designed in 1890 by Barnett, Haynes and Barnett, offers another Romanesque Revival dwelling that challenges the heaviness of the style through use of flat-faced ornamental elements and a compositional delicacy. The limestone classing and massing are in league with Duncker’s residence. Most closely related to the Duncker Residence may be Weber & Groves’ Frederick Newton Judson Residence on Washington Avenue (1892), a red brick and sandstone cousin with comparable execution of entrance, massing and roof form.

According to the 1906 edition of The Book of St. Louisans, Charles H. Duncker (1865-1952) was a carpet merchant who served as vice president of Trolicht, Duncker & Renard Carpet Company (then located at the southeast corner of 4th and Washington streets downtown). Duncker had wed Pauline Doerr and together they had two children. Duncker was a member of the Union and Missouri Athletic Clubs. By the 1912 edition of The Book of St. Louisans, Duncker’s firm had changed its name to Trolicht & Duncker in 1907, and Duncker was now company president. The Republican Duncker was a member of the progressive Civic League as well as the Academy of Science of St. Louis.

The Dunckers kept up with both architectural and geographic fashion, and departed Page Boulevard in 1916. The family built a new house at 15 Brentmoor Park in a picturesque garden subdivision designed by Henry Wright. The new Duncker mansion, which would later be published in Missouri’s Contribution to American Architecture, was a resplendent Jacobethan mass adorned with patterned matte brickwork, ornate vergeboards, applied timbering and tall chimneys. Cann & Corrubia designed the house, and landscape architect John Noyes designed the grounds.

Later, the Dunckers lost son Charles Jr. when he fell in combat in France in 1917. The family funded a memorial hall on Washington University’s campus, completed in 1923 as Charles H. Duncker Hall (or, Duncker Hall, where the English Department now can be found). Charles H. Duncker insisted that Cann & Corrubia design the hall, making it the only hall built in the historic hilltop main quadrangle not primarily designed by Cope & Stewardson or James P. Jamieson.

Reborn as the Jewish Community Center

In 1919, the United Hebrew Association acquired the Duncker Mansion, and converted it into the precursor of today’s Jewish Community Center. By this time, St. Louis’ Jewish population had largely relocated from inner city neighborhoods east of Grand Avenue. Concentrations of Jewish population found north of downtown, like Carr Square and around Biddle Street had shifted westward along street car lines into more suburban enclaves including Mt. Cabanne-Raymond Place and the area of Hamilton Heights south of Easton Avenue (now Dr. Martin Luther King Drive). The Duncker residence was on the eastern end of Jewish world at the time, but its location along the Page Boulevard street car line made it convenient to much of the Jewish population in the city.

In Zion of the Valley, historian Walter Ehrlich writes that it was at the Duncker residence on April 4, 1921 that the Federation of Orthodox Jewish Charitable and Educational Institutions of St. Louis was born. Despite some dissent within the community, over 200 prominent Orthodox Jewish leaders met that day to unify Orthodox institutions through a new federation similar to one that the Reform community has just created. The federation’s first president was Hyman Cohen, who led a structure that included a board of directors and an impressive 60-person advisory board. The congregations Chesed Shel Emeth (located in a synagogue at Page and Euclid since 1919) and Shaare Zedek (located at Page and West End since 1914, in a building that is now Pleasant Green Missionary Baptist Church) were member organizations, alongside Orthdox Jewish Old Folks Home (located nearby on North Grand Avenue; still extant) and other institutions.

Some members of the Orthdox community felt that the formal separation of Orthodox institutions reinforced existing needless divides, and their views prevailed soon. In 1925, the Orthdox federation merged with the Federation of Jewish Charities of St. Louis. The unified organization to this day remains named the Jewish Federation of St. Louis. Inside of the stone castle on Page, this organization and others were very prosperous in the 1920s and 1930s. The United Hebrew Association is responsible for the addition of a two-story brick addition at the rear of the building. The city issued a building permit for that addition on May 10, 1920; the construction cost was $19,500. The two-story flat-roofed brick addition houses class and meeting rooms.

As the Jewish population continued to move away from Grand Avenue during the Depression years, the location of the Jewish Community Center became an inconvenient anachronism, and the center moved in 1943. Eventually, the Jewish Community Center would built a new facility in Creve Couer called the I.E. Millston Campus, which opened in 1963. That center remains open today, disconnected in all but perhaps a fraction of regional memory from the turreted mansion on Page Boulevard.

From the Colored Old Folks’ Home to Page Manor

In 1943, the Colored Old Folks’ Home purchased the property. Founded in 1902 by the Woman’s Wednesday Sewing Club, whose members raised funds to create it, the Home later became the Ferrier-Harris Home. Rose Ferrier-Harris had been first president of the Sewing Club. For decades, this building was a landmark to the charitable efforts of African-American women, and the home merited listing in John A. Wright’s Discovering African-American St. Louis. Upon purchase, the Colored Old Folks’ Home spent a reported $3,000 to alter the building, according to a building permit issued on January 27, 1943. However, the character of the main section and rear carriage house were left intact.

Eventually the revered Ferrier-Harris Home became the Page Manor, which did not sustain the good quality and noble purpose of the prior operator. The Missouri Department of Health and Senior Services notified Page Manor’s owners of major violations starting in 2012, and earlier this year succeeded in revoking the license of the facility. Page Manor closed, and its owners decided to apply for a demolition permit for the complex.

Since the city’s preservation review system is based on political considerations, not professional standards, neither the architectural grandeur nor the varied history of the former Duncker residence slowed demolition. The city’s Cultural Resources Office never had any authority to review the demolition application, and there was no public meeting or call for public comments. Instead, the Building Commissioner issued a demolition permit with little public attention, and a very significant part of the city’s history began to be erased.

Lest one assume that this pocket of the 19th Ward is bereft of context, or that this author is guilty of inordinate adulation of old building fiber, consider the surrounding urban fabric in which the Duncker residence played a role. While across Page is the suburban expanse of a strip retail center, the block on which the house had stood includes several significant historic dwellings. Along Grand Boulevard around the corner are historic houses, including one designed by the quintessential local architectural firm of Barnett, Haynes & Barnett. All lack any demolition protection, since none are official City Landmarks and none is listed in the National Register of Historic Places.