St. Louis’ Tower Grove East Neighborhood — where the Preservation Research Office currently is located — has a new website, built and designed by neighborhood resident Joe Millitzer.

St. Louis’ Tower Grove East Neighborhood — where the Preservation Research Office currently is located — has a new website, built and designed by neighborhood resident Joe Millitzer.

Check it out at www.towergroveeast.org

St. Louis’ Tower Grove East Neighborhood — where the Preservation Research Office currently is located — has a new website, built and designed by neighborhood resident Joe Millitzer.

St. Louis’ Tower Grove East Neighborhood — where the Preservation Research Office currently is located — has a new website, built and designed by neighborhood resident Joe Millitzer.

Check it out at www.towergroveeast.org

by Michael R. Allen

The storefront additions at 4035 (left) and 4033 (right) Delmar Boulevard in slightly better condition last year.

Last month, I reported that the large apartment building at 4011 Delmar Boulevard was on the market again. Down the block to the west, another story is unfolding — and I see an unhappy ending in the works. The elegant but abandoned town house at 4035 Delmar Boulevard, shown above, and its streamlined two-story storefront addition are in trouble. (More information about the storefront additions on this block can be found in this post from last year.)

4035 Delmar Boulevard last month.

4035 Delmar Boulevard last month.

First, something — perhaps an automobile — smacked into the corner of the storefront addition. The corner of that section is settling something fierce. Now, there is gaping hole in the front of the house that continues to grow wider.

If the property was owned by the city, its demise would all but be assured. However, property tax records show that the owners live in Israel. Perhaps the owners are aware of the building’s condition, but there has been no indication borne out in repair. No doubt that we will watch a slow death unfold — for shame.

Some readers may find the contrast between the faded beauty of the house and the modern lines of the storefront jarring. Yet I see the simultaneous presence of two phases of the Vandeventer neighborhood’s life, and soon-to-be squandered potential for rebirth.

by Michael R. Allen

The Chemical Building in 2005.

The Chemical Building in 2005.

Today’s news that the owners of the venerable Chemical Building at 8th and Olive streets have filed bankruptcy bring uncertainty to the future of their redevelopment plan. The welcome prospect that the name might not change to “Alexa” aside, the turn toward bankruptcy has some tongues wagging that downtown will have two big vacant buildings at the intersection for a long time. Diagonally across the intersection is the Arcade Building, now owned by a city agency after the Pyramid Companies declared bankruptcy and the building went to foreclosure auction.

Whether the molasses-slow market can absorb so much square footage of adaptively reused space is unknown. What is known is that taking a fully-occupied building like the Chemical and dumping all tenants before full financing is ready for rehabilitation is not a good idea (see also: Jefferson Arms). Had the developers waited, they might be waiting out the recession with a highly desirable low-rent refuge for small businesses.

The Union Trust Building today.

The Union Trust Building today.

No matter — the Chemical Building has an architectural history trump card that guarantees all is not lost. See, the as-built Chemical Building design by Boston-born Henry Ives Cobb triumphed over one by Chicago wunderkind Louis Sullivan. St. Louis was a remarkably receptive place for Louis Sullivan’s art, and the 700 block of Olive Street could have had side-by-side Sullivan. The Union Trust Building at 705 Olive had been completed in 1893, and its stunning round windows, exposed light well, terra cotta lions and monochromatic buff brick and terra cotta shaft all proudly brought Sullivan’s revolution to town. (The Wainwright Building of 1891 was no small achievement, but the local press took greater notice of the Union Trust.)

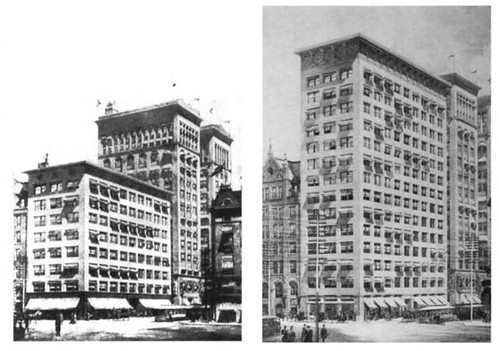

Two plans for the Chemical Building by Louis Sullivan, exhibited at the Third Annual Exposition of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1895.

Two plans for the Chemical Building by Louis Sullivan, exhibited at the Third Annual Exposition of the St. Louis Chapter of the American Institute of Architects in 1895.

The Chemical National Bank planned a complementary, modern office building adjacent to the Union Trust. In 1894, the bank solicited the two proposals by Sullivan shown above. The difference between the two possible plans is primarily height; the gridded bodies are otherwise almost identical. With wide double windows, large round windows at the attic and a large overhanging cornice, the proposed buildings would have been very striking for both the time and place. However, their form certainly would have paled in comparison to the sheer genius of the Union Trust. Sullivan may have wished to touch his masterpiece with a gentler neighbor.

Instead of a gentle lesser work by Sullivan, the Chemical National Bank directors chose a rather bold 17-story design by Cobb. Cobb’s plan originally fronted only four bays on 8th Street, and was extended by five bays in 1903 from near-seamless plans by Mauran, Russell & Garden. Cobb’s building had a rather old-fashioned two-story cast iron base by Christopher & Simpson that was heavily ornamented in classically-derived foliated patterns. However, the upper floors were built out in a monotone of brick and Winkle terra cotta. The projecting trapezoidal bays, including a dramatic chamfered corner bay, emphasized the building’s height as much as the Union Trust’s piers. Yet the horizontal band courses dampened the effect of the bays, and the fenestration between the projecting bays was far from expressive of the building’s structural grid. The top two floors were clad in ornamented terra cotta.

Cobb tried to marry the Chicago School skyscraper with the nobility of traditional masonry ornament, and the result was panned in 1896 upon completion of the Chemical Building. With Sullivan looming next door, comparison was inevitable — and unfavorable. In 1896, an anonymous correspondent wrote in The Brickbuilder of the architect’s effort to express the Chemical Building: “He has left no quiet spot upon which we may rest the eye, and, although we may be awed by its great height, it lacks the simplicity and imposing grandeur of its neighbor, the Union Trust Building.”

The Chemical Building and the Union Trust Building, monochromatic neighbors from the 1890s.

Today, that assessment of the Chemical Building seems hasty. While Cobb’s work largely exhibits few progressive tendencies in an age of innovation — although it includes Chicago’s elegant Newberry Library (1893) — the Chemical Building is the architect’s strongest commercial design. The reference to Chicago’s long lost Tacoma Building by Holabird & Roche (1886-9) is obvious, but not the source of the Chemical Building’s design inspiration. Cobb could easily have mimicked Sullivan or other better-regarded luminaries of the Chicago School, but he chose instead to offer his own vision.

The Chemical Building’s red monotone is impressive and striking, and draws the eye toward itself with as much force as the Union trust or Wainwright. The Chemical Building is a fitting neighbor to the mighty Union Trust, and holds its own with a rather different statement about the tall building’s artistic potential. Together, the two buildings in their contrasting tones show us a full range of architectural imagination in the late 19th century. The Chemical Building’s horizons contrast effectively with the Union Trust’s swaggering vertical elements, reminding us that a tall office building is also a stack of floors where people work.

One without the other would be an incomplete range and, had the Chemical National Bank chose Sullivan to complete the block face to his measure, two of the same would not so powerfully urge the eye to fix on two powerful, beautiful masses. There is no doubt that the Chemical Building has good fortune on its side.

by Michael R. Allen

Last month, we visited Tulsa on what was planned as a vacation. Somehow we ended up often rising earlier and looking at more buildings per day than we ever do back home. These things happen, I suppose. I am just glad that our exploring led us to the inspiring Tulsa Foundation for Architecture (TFA; blog here). TFA is a small, young organization that has already built an array of program activities that would be daunting even for a more established organization. Founded by the Eastern Oklahoma chapter of the American Institute for Architects in 1995 — a mere fifteen years ago — TFA is a strong advocate for preservation, a force for education through tours and events, publisher of books, sponsor of “>Modern Tulsa convener of conferences and — most impressively — steward of a massive archive on Tulsa’s architectural history. Oh, and TFA collects architectural artifacts too!

TFA’s office is in the basement of the Kennedy Building in downtown Tulsa. Archivist Derek Lee kindly guided us through our surprise visit one morning. The staff members’ two desks are in corners, with most of the space devoted to metal shelving and flat files housing some 35,000 drawings from major architectural firms’ offices. The windows to the corridor are filled with colorful artifacts, including polychomatic terra cotta with Art Deco motifs. It’s as if a smaller version of the St. Louis Building Arts Foundation and the Landmarks Association of St. Louis were joined together.

TFA’s mix is exciting and successful: the organization is buying a building that will increase space and, most importantly, visibility. Plus, the National Historic Records Advisory Bureau has proclaimed TFA as a model archival organization.

However, TFA’s biggest accomplishment stands outside of its office: the restored Meadow Gold sign on 11th Avenue, which was Route 66 in Tulsa. Located near downtown, the 1930s-era sign faced an uncertain future for many years. TFA obtained a grant for restoration from the National Park Service Route 66 Corridor in 2004, but the sign and the building atop which it sat were privately owned. When the owner planned demolition, TFA worked with the City of Tulsa to save and reconstruct the sign.

TFA’s work to actually save the sign accompanied a survey of 259 neon signs in the Tulsa area. This survey resulted in the just-published booklet Vintage Tulsa Neon Signs, a brief and colorful introduction to a threatened resource. This booklet joins TFA’s reprint of the exhaustive and lovely Tulsa Art Deco by Carol Newton Gambino and David Halpern as a powerful educational tool. We salute our busy colleagues in Tulsa and await good news of their future endeavors!

From Preservation Action

On Thursday of this week, before adjourning for the midterm elections, Congress passed a stopgap funding measure to keep the federal government operating until December 3rd. The 2010 Fiscal Year ended at midnight yesterday. As was expected, funding was extended, with a few exceptions, at FY 2010 levels.

The passage of the measure, usually referred to as a Continuing Resolution or “CR,” puts off what are expected to be particularly hostile spending decisions until after the midterm elections. However, while the Democrats are saying they plan on settling FY 2011 appropriations bills during the lame duck session (the period between the midterm elections and the beginning of the new legislative year), Republicans are hoping to further delay spending decisions until the next Congress when they may have control of one or both chambers.

With funding in the Administration’s proposed FY 2011 budget eliminated for Save America’s Treasures and Preserve America, and cut in half for National Heritage Areas, an extension at FY2010 levels is positive for preservationists. While Congress has been receptive to the notion of retaining funding for these programs in their subsequent spending bills, to date neither chamber has passed such a bill or given an indication of what the funding levels would look like.

Lame Duck Likely To Be Lame For Preservationists

With Congress adjourned after passing little more than the CR, and a full slate of spending bills that will need to be dealt with for FY 2011 upon their return on November 15th after contentious midterm elections, the jury is out on what else they will be able to focus on. Sources are telling us that the likelihood of the Senate taking up an energy bill, such as either S. 3663 or or H.R. 3534 (the CLEAR Act), are very slim. While the former contains full-funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF), the latter contains both full funding for the LWCF and the Historic Preservation Fund. Preservation Action and its partners have been advocating for the Senate passage of the CLEAR Act for several months.

In addition to appropriations, likely candidates for consideration are the extensions to the Bush era tax cuts, and “New Start,” a new arms control treaty with Russia. Any introduced bills that do not get signed into law before the end of 111th Congress will die and would have to be reintroduced in the 112th Congress, which begins January 3, 2011.

The Sheldon Art Galleries will unveil several fantastic exhibits tonight from 5:00 p.m. through 7:00 p.m. Two of these exhibits will be of great interest to readers of this blog.

Designing the City: An American Vision

October 1, 2010 – January 15, 2011

Drawn from the Bank of America collection, this exhibition offers a unique opportunity to see some of the great architectural works built across America and the cities for which they are an integral part. Photographers included are Berenice Abbott: Harold Allen; Bill Hedrich, Ken Hedrich and Hube Henry of the Hedrich-Blessing Studio; Richard Nickel; and John Szarkowski. It is through photographs that most of us have come to know major works of architecture. Our experience of great architecture is often not at the building’s actual site, but rather through a two-dimensional photographic rendering of it. In fact, for many buildings, photographs are all that remain. The term, “architectural photography” is widely used and generally understood to describe pictures through which the photographer documents and depicts a building in factual terms. However the artists featured in this exhibition have taken architectural photography beyond its informative purpose and have shown us the importance of architecture in the definition of the urban American landscape.

Group f.64 & the Modernist Vision: Photographs by Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, and Brett Weston

October 1, 2010 – January 15, 2011

Seminal works by renowned photographers Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Willard Van Dyke, and Brett Weston, including several spectacular large-scale prints by Ansel Adams — among them Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico, 1941 — as well as Edward Weston’s iconic Pepper, 1930, and examples of Imogen Cunningham’s beautiful and sculptural flower closeups are shown in this exhibition alongside rarely seen works by the artists, all drawn from the Bank of America collection.

Founded in 1934 by Willard Van Dyke and Ansel Adams, the informal Group f.64 were devoted to exhibiting and promoting a new direction in photography. The group was established as a response to Pictorialism, a popular movement on the West Coast, which favored painterly, hand-manipulated, soft-focus prints, often made on textured papers. Feeling that photography’s greatest strength was its ability to create images with precise sharpness, Group f.64 adhered to a philosophy that photography is only valid when it is “straight,” or unaltered. The term f.64 refers to the smallest aperture setting on a large format camera, which allows for the greatest depth of field and sharpest image.

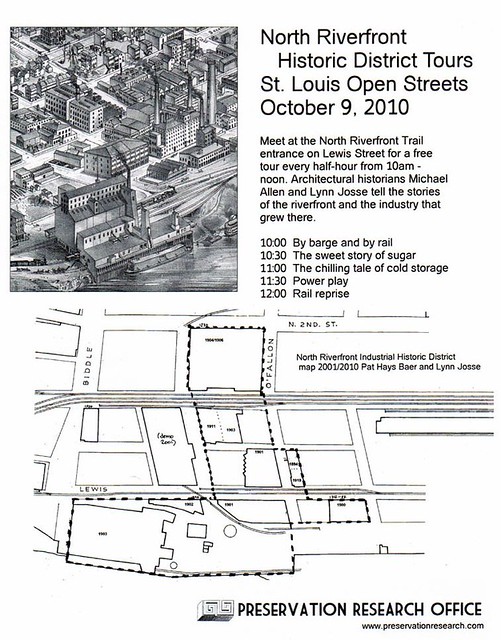

Tour starts near the St. Louis Cold Storage and Refrigeration Company Warehouse at Lewis & O’Fallon Streets (1901; Widmann, Walsh & Boisselier)

Tour starts near the St. Louis Cold Storage and Refrigeration Company Warehouse at Lewis & O’Fallon Streets (1901; Widmann, Walsh & Boisselier)

Architectural Tour of the Industrial North Riverfront

Saturday, October 9 (part of Open Streets)

Short walking tours every half hour, 10 a.m. – Noon

Meet around the North Riverfront Trail entrance on Lewis Street

The Preservation Research Office is pleased to join the City of St. Louis for the next Open Streets Day. Architectural historians Lynn Josse, author of the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the district, and Michael R. Allen will lead guided tours of the industrial world of the north riverfront around the trail head. See the St. Louis Cold Storage warehouse, the massive Ashley Street Power House, a charming former bath house renovated using green technology, the birthplace of graniteware and other sites. Tours approximately 20 minutes. Informational flier will be distributed.

by Michael R. Allen

Brick theft is an act that is neither novel nor particularly likely to spur strong response in St. Louis. Malcolm Gay’s excellent recent New York Times article on brick theft in St. Louis reported to the nation what has become a sad backdrop to life in distressed neighborhoods of the city for decades. In the thirty odd years that illegal destruction of brick buildings has hit the city, especially the north side, few efforts have been made to increase legal penalties for the action. There is outrage in the streets, but the dealers who buy stolen brick still sleep peacefully in their own homes when sun sets.

Once when I wrote about brick theft in this blog, I received a thoughtful comment that likened brick thieves to fungi that consume fallen trees in the forest. The commenter suggested that an organic and harmless transaction occurs when a supposed useless old brick building is picked apart by thieves that often set the buildings afire first and leave a dangerous pit behind. Gay’s article let us know that the arson that precedes brick theft has collateral damage that cannot be rationalized under a theory of urban material reclamation. The notion that thieves are recycling neglected material is belied by the fact that their methods are far from systematic, and so much useful material is left to be placed in landfills. Demolition contractors — who lose hours of paid work to the thieves — may be the fungi that tackles the city’s building stock, but brick thieves are more akin to the loggers that rob forests of their most valuable wood, leave behind a damaged ecosystem that others must mend.

I thought about the comment on brick theft when I examined what remains of the North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church at 2940 Montgomery Avenue in JeffVanderLou, now owned by Northside Regeneration LLC. The brick church, built in 1900, recently was cleaned of its side walls by thieves who have systematically worked the surrounding buildings as well. There seems to be no compunction halting the destruction of a historic house of worship.

North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church, April 2009

North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church, April 2009

North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church, August 2010

North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church, August 2010

There would be many who would argue that this old church was a useless remnant of a lost neighborhood, and that its gruesome demolition mandates no more than a passing word or a Flickr photograph. They are wrong. The church served its function for over 100 years, only going vacant a little over three years ago. While the building had been altered beyond the criteria of architectural integrity required for listing in the National Register of Historic Places, it remained the embodiment of decades of African-American worship and community life. Churches are their people, but church buildings are stores of memory worthy of our care. The North Galilee Missionary Baptist Church building deserved a more dignified end, and the brick thieves and their clients ought to suffer significant penalty. The New York Times article should not be shaken off as “bad press” but taken as a call to action.

Bike the Belle!

Saturday, October 2 · 10:00am – 11:30am

Bellefontaine Cemetery – 4947 West Florissant Ave

Join Metropolis St. Louis for a 4 mile bike ride through historic Bellefontaine Cemetery.

Founded in 1849, the cemetery includes the graves and tombs of many notable St. Louisans such as Adolphus Busch and General William Clark.

** We will also have the opportunity to go inside the Wainwright Tomb and the Lemp Family Tomb.

Meet at the main entrance on W. Florissant Ave, park anywhere along the street. Take Hwy 70 to W. Florissant, do it.

FREE! Just bring your bike. Walkers are also welcome.

Visit http://www.mstl.org/ for more information and http://www.bellefontainecemetery.org/ for information on the cemetery.

by Michael R. Allen

Today was a lovely day on the near north side of our fair city. At 14th Street in Old North, the two-block former pedestrian mall now has a paved street, full sidewalks and street signs. With the addition of street lights, all will be set for the final opening of 14th Street in the heart of the neighborhood.

Today was a lovely day on the near north side of our fair city. At 14th Street in Old North, the two-block former pedestrian mall now has a paved street, full sidewalks and street signs. With the addition of street lights, all will be set for the final opening of 14th Street in the heart of the neighborhood.

Up in Hyde Park, as I attended a meeting I heard the clamor of tools around 19th and Mallinckrodt streets. The sounds were unmistakable, and plainly beautiful to hear. They came from two buildings on each side of 19th street in block south of the park. Eliot School LP is rehabilitating these 19th century brick buildings for housing. The long-vacant single family home shown here will hold multiple families.

Up in Hyde Park, as I attended a meeting I heard the clamor of tools around 19th and Mallinckrodt streets. The sounds were unmistakable, and plainly beautiful to hear. They came from two buildings on each side of 19th street in block south of the park. Eliot School LP is rehabilitating these 19th century brick buildings for housing. The long-vacant single family home shown here will hold multiple families.

Another vacant four-family will remain in service as a multi-family building, maintaining the residential density that enlivened Hyde Park in the past. Nearby, Salisbury Avenue is getting new sidewalks and street lights. The Salisbury project is in full swing as well, causing traffic to back up around the entrance to the McKinley Bridge. Let no one mistake the sidewalk work for anything other than a catalyst for future growth. Salisbury offers potential for infill construction and rejuvenated mixed-use buildings. Apartments in solely residential buildings are a great part of neighborhood life, but not the only one. The buildings being rehabbed now will someday join a wave of mixed-use buildings old and new on one of the north side’s most humanely-scaled commercial streets. Both 14th Street and Salisbury are central to neighborhood economy, and while much has been renewed around them their historic function — facilitating exchange through commerce – is fragile.

Another vacant four-family will remain in service as a multi-family building, maintaining the residential density that enlivened Hyde Park in the past. Nearby, Salisbury Avenue is getting new sidewalks and street lights. The Salisbury project is in full swing as well, causing traffic to back up around the entrance to the McKinley Bridge. Let no one mistake the sidewalk work for anything other than a catalyst for future growth. Salisbury offers potential for infill construction and rejuvenated mixed-use buildings. Apartments in solely residential buildings are a great part of neighborhood life, but not the only one. The buildings being rehabbed now will someday join a wave of mixed-use buildings old and new on one of the north side’s most humanely-scaled commercial streets. Both 14th Street and Salisbury are central to neighborhood economy, and while much has been renewed around them their historic function — facilitating exchange through commerce – is fragile.