by Michael R. Allen

Across Chouteau Avenue from the Pevely Dairy Plant, St. Louis University has cleared several older industrial buildings. In recent days, the straw-strewn vacant lot has been awash with birds picking out the grass seeds. This prominent location, elevated above Grand Avenue to the east, now will sit idle for the time being. St. Louis University, a non-profit corporation, will not pay real estate taxes on this valuable central corridor site. Until developed, the site is producing absolutely nothing in economic good for the city.

Jeremy Claggett posted an article at nextSTL that shows how the university’s proposed ambulatory care center could occupy this newly-cleared land mass. Construction could start immediately, and the value of the Pevely Dairy Plant would increase with the investment across the street.

In the early twentieth century, urban planning became a function of city government in order to curb rampant private misuse. At its best, municipal planning ensures thoughtful lands stewardship remains an enforceable public good. This happens through a priori guidance — comprehensive planning. Commissions’ denying demolition permits serves as a negative force that can prevent careless losses of historic buildings with cultural and economic value, but such denials do not constitute effective urban planning.

St. Louis University’s land acquisitions around the medical center demonstrate that in the absence of strong municipal planning, the university has created its own comprehensive plan. That plan may lead to job creation and provision of some public goods, like ambulatory care, but it remains a plan to achieve private institutional goals. The university’s wishes for future development of the corner of Grand and Chouteau may coincide with the public good, but they are not responsive to it.

At present, the public good is manifest through citizen power brought to public meetings at the Preservation Board, Board of Aldermen and other venues. Citizens have asserted that the public good is not served by allowing demolition of the Pevely Dairy when the university has enough land to build ten ambulatory care centers and still leave the historic dairy plant standing. All people are saying is that the university’s planning should be subsumed to the interests of the entire city.

The interests of the city are not served by the university’s land-banking, nor by the university’s wanton demolition of buildings listed in the National Register of Historic Places (a not-easy-to-obtain federal designation created in 1966 that represents the public interest). The absurdity of taking down the Pevely Plant when there is a giant, fresh moonscape across the street is clear to the public, the majority of Preservation Board members and seemingly to Mayor Francis Slay. That’s a glaring point of contest, though. The larger issue remains more diffuse: St. Louis University’s planning for the medical center area is happening without the presence of assertive municipal comprehensive planning. The Pevely Dairy demolition won’t be the last battle here.

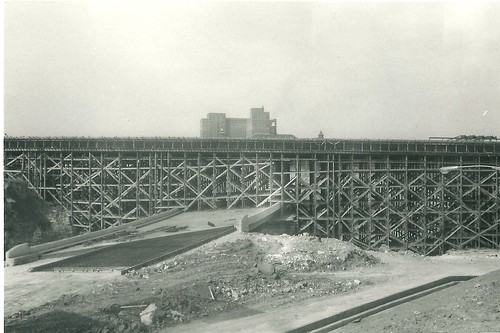

Looking east near the intersection of McRee and Lawrence avenues.

Looking east near the intersection of McRee and Lawrence avenues.