This view looking east at the Grand Avenue Water Tower dates to February 1957 and was taken by the City Plan Commission.

This view looking east at the Grand Avenue Water Tower dates to February 1957 and was taken by the City Plan Commission.

Category: Hyde Park

by Michael R. Allen

Did you ever see this lovely building at the southeast corner of 20th and Farragut streets? Too late now. While you soon can park on top of the site in a city-funded parking lot, you won’t be able to ever look at this corner store in Hyde Park again. Demolition of this building and two others on north 20th street between Penrose and Farragut — all contributing resources top the Hyde Park Historic District — started in February and wrapped up this week.

Did you ever see this lovely building at the southeast corner of 20th and Farragut streets? Too late now. While you soon can park on top of the site in a city-funded parking lot, you won’t be able to ever look at this corner store in Hyde Park again. Demolition of this building and two others on north 20th street between Penrose and Farragut — all contributing resources top the Hyde Park Historic District — started in February and wrapped up this week.

How did demolition pass by the Cultural Resources Office and the Preservation Board? As is often the case, the Building Division issued an emergency demolition order (on December 16, 2008) that trumped preservation review. Never mind that these buildings were sound under both the city’s preservation ordinance and public safety laws. The Building Division deemed that their sound condition somehow was an imminent danger to public safety. Or, perhaps, imminent danger to the neighboring occupant of the old Penrose Police Station at 1901 Penrose: the parking meter division of the City Treasurer’s Office.

The building at the northwest corner of Penrose and 20th streets.

The building at the northwest corner of Penrose and 20th streets.

The City Treasurer’s Office has owned the lots on which the buildings sat for years. While these buildings could have been sold to tax-paying developers, the Treasurer’s Office decided to instead wreck them, remove taxable improvements from the land and keep the land under city ownership. Perhaps there is an ultimate development plan (hopefully not a parking lot, which would be absurd). For now, though, there is just another vacant lot in an area where there seem to be more vacant lots than buildings.

The lost buildings formed a remarkable group worthy of protection, and I regret never photographing them until demolition had commenced. The corner storefront at 20th and Penrose dated to 1895 and, while not overly ornamented, had a handsome cast iron storefront and chamfered corner. I don’t recall much about the house across the alley to the north, but its history was interlocked with its lavish neighbor to the north, shown in the first photograph above. That house, located at 4220 N. 20th, was home of Charles A. Roettger, who developed the storefront at 4222-24 N. 20th in 1907. According to its permit, the new building cost $9,800 to build — no small sum then.

To design this building, Roettger employed a distinguished north St. Louis architect, Otto J. Boehmer. Boehmer designed the perpendicular Gothic sanctuary of Friedens United Church of Christ (1908) nearby at the southwest corner of 19th & Newhouse streets. Boehmer also resided at 3500 Palm Street in Lindell Park from 1914 through 1933 — the house now occupied by former mayor Freeman Bosley, Jr., son of the alderman who represents the site of the new parking lot. The contractor for the new building was also a north side of German ancestry: Leo Motzel of 2217 College Avenue.

The corner storefront was a masterpiece of vernacular use of the Tudor Revival style. The corner turret, tiled roof with its false dormers, half-timbering and copper cornices are all fine decorative elements that created one of Hyde Park’s most picturesque corner stores. The building housed Frank C. Roettger’s (Charles’ brother) meat shop at the corner for decades following its construction. Another early tenant was Flora Loewenthal’s cigar shop at 4222 N. 20th.

The city directory listings name tenant after tenant in these buildings. The names shift from German-American to African-American at some point, until the word “vacant” pops up. Reading the names in the city directory and thinking about the loss of the buildings, one tracks not simply a loss of architectural stock, but a loss of life — lost names, lost uses and lost activity.

by Michael R. Allen

All across the city are examples of residential buildings adapted to later commercial use. As neighborhoods changed, so did uses. In early 19th century walking neighborhoods, commercial uses needed to be abundant to serve residents who could not travel far to get food, shoes or a hair cut. Later, after the streetcars gave middle- and working-class residents greater mobility, residential buildings located along street car lines were ripe for commercial use, especially in areas where property values declined because of the new street car lines.

Many examples of the common storefront addition involve the construction of connected one- or two-story buildings in the lawn space of houses and flats. However, in neighborhoods east of Grand, many early converted buildings stood at the sidewalk line. Here, the best way to create commercial space was through the insertion of storefront openings in existing front elevations. Typically, cast iron columns and combined beams would “jack” the new opening in the brick wall. Often, floor levels inside of the building would be altered to draw the shop floor down to sidewalk level from is common position at the head of foundation walls.

Two examples of similar buildings from different neighborhoods illustrate how this practice happened across the city.

by Michael R. Allen

Eleventh Street continues north of Branch Street for two blocks, abruptly dead-ending where it meets the embankment of I-70. I-70 hems in the street and the pocket of residential Hyde Park that remains severed from the neighborhood. The city furthered this severance by officially drawing the Hyde Park boundary at I-70, which is certainly a barrier but nothing that defines any boundary of a neighborhood that has always started at the Mississippi River.

Eleventh Street continues north of Branch Street for two blocks, abruptly dead-ending where it meets the embankment of I-70. I-70 hems in the street and the pocket of residential Hyde Park that remains severed from the neighborhood. The city furthered this severance by officially drawing the Hyde Park boundary at I-70, which is certainly a barrier but nothing that defines any boundary of a neighborhood that has always started at the Mississippi River.

I love these two houses on the west side of Eleventh Street north of Branch. There are many small shaped-parapet bungalows in Hyde Park, built of pressed brick with wooden front porches. Houses like these line Agnes and Destrehan streets back in official Hyde Park. These homes date to the 1920s, when they went up en masse on undeveloped sites in the south end of the neighborhood. Few of those houses enjoy as dramatic a setting as these two now do. The highway in the back yard, giant billboards on each side — the only comfort found in one of these houses is its well-kept neighbor. The brick sidewalk in front adds another reminder of the lost connection with the historic world of Hyde Park.

by Michael R. Allen

This house stands in Hyde Park on the west side of Vest Avenue just north of Bremen Avenue. Despite some obvious maintenance needs, the house is a treasure. This is one of the small houses that have a front-gabled salt box roof profile. I think of these houses as cousins to our city’s flounder houses, whose roofs make a slope from one side to the other. The salt box variation has a roof profile common around the country, but the basic form and size of the house is akin to the small flounder houses that one still finds all over the city east of Grand Avenue.

This house stands in Hyde Park on the west side of Vest Avenue just north of Bremen Avenue. Despite some obvious maintenance needs, the house is a treasure. This is one of the small houses that have a front-gabled salt box roof profile. I think of these houses as cousins to our city’s flounder houses, whose roofs make a slope from one side to the other. The salt box variation has a roof profile common around the country, but the basic form and size of the house is akin to the small flounder houses that one still finds all over the city east of Grand Avenue.

On the next block of Vest to the south stands another small house. This one is of a different but common type, that of the two-story mansard-roofed home in which the mansard roof forms the second floor. These houses are more common than either the flounder or the saltbox, but typically are also small in size.

On the next block of Vest to the south stands another small house. This one is of a different but common type, that of the two-story mansard-roofed home in which the mansard roof forms the second floor. These houses are more common than either the flounder or the saltbox, but typically are also small in size.

Taking the wide view of this block, we see two other small houses and some vacant lots. Some two-story houses are down the block and across the street.

Looking up to the next block north, we find vacant land and the one-story salt box house. Some two-story houses are down the block and across the street.

This west end of Hyde Park developed slowly in the 19th and early 20th centuries, and the results are neither as consistent or as dense as the eastern part of the neighborhood. The west end was far less desirable as a place to live due to the presence of the meat packing industry, which was centered on Florissant Avenue. The Krey’s Packing plant and a few other packing-related buildings stand, but much of the rest is gone. The packing industry was largely lost to the National City Stockyards in Illinois by the early 20th century, so later residential development in western Hyde Park produced larger buildings. The early houses were modest in scale, many only one story tall. The residents worked nearby at the packing houses or the Hyde Park brewery.

The 1909 Sanborn fire insurance map shows over a dozen one-story houses on the two blocks of Vest Avenue profiled here. Less than six remain. The remaining small houses point to a residential economy lost to rising Gilded Age fortunes. Nowadays, in the wake of the McMansion glut and with the American economy on the brink of collapse, small houses do not seem so bad. Necessity led to construction of the small houses on Vest, and necessity may make them attractive 21st century housing options.

A new ballpark is proposed east of here on Florissant Avenue, and revitalization efforts around Bethlehem Lutheran Church and Irving School have changed this west end of the neighborhood into a livable place. New housing has gone up on 22nd and 25th streets, but the larger market-rate homes have limited demand. Perhaps an alternative market-rate infill project is in order on Vest Avenue. The vacant lots offer the opportunity to again build small houses there to create affordable, low-energy houses. Small houses already cost less to heat and cool, and are easier to make passive than larger homes. The size makes them more affordable, and also expandable. The first home shown above has an addition on its south side, and others shown on the Sanborn map have one or two rear additions. Such flexible, small houses are in short supply in St. Louis. Development of more needs to happen.

by Michael R. Allen

The Missouri Housing Development Commission (MHDC) has published staff recommendations for tax credit allocations to be made at the December 12 MHDC meeting. Noteworthy is that the Junction development in Old North (“‘The Junction’ and Old North’s Housing Balance,” November 29) is not among the projects recommended for approval of 9% federal low income housing tax credits. St. Louis projects recommended for approval are the Dick Gregory Place project in the Ville and new phases in the North Newstead Association’s ongoing project in O’Fallon and Better Living Communities’ project in Hyde Park.

by Michael R. Allen

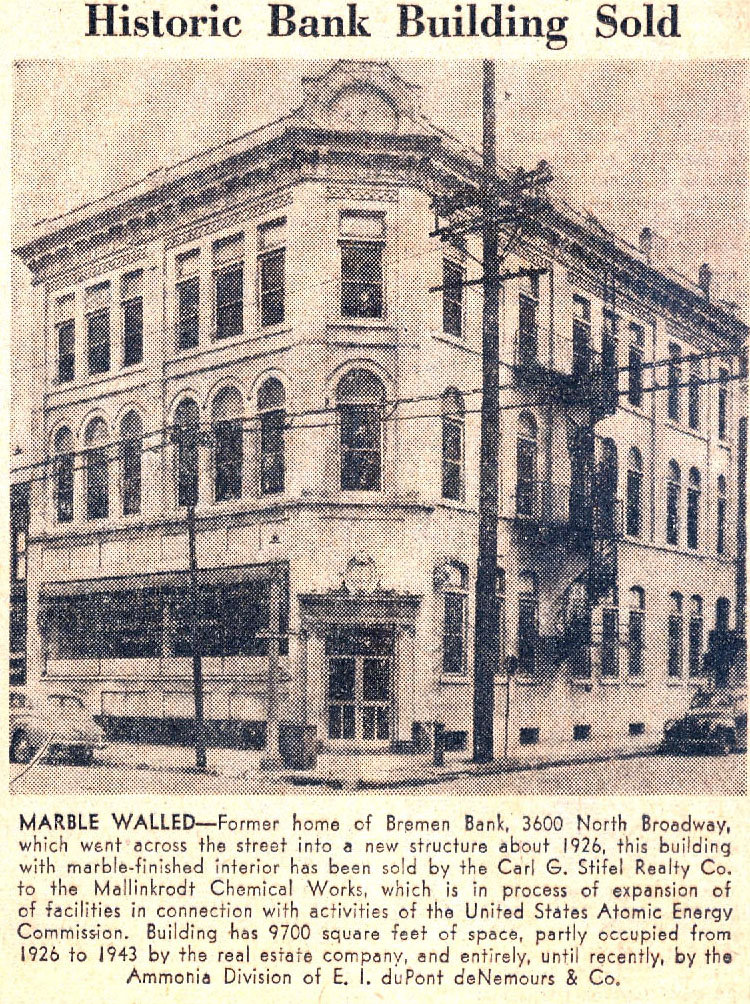

The following scanned clipping comes from the January 9, 1949 edition of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch:

Some readers know of the 1927 Bremen Bank building diagonally across the intersection of Broadway and Mallinckrodt streets; that lovely historic building remains the home of the Bremen Bank.

Some readers know of the 1927 Bremen Bank building diagonally across the intersection of Broadway and Mallinckrodt streets; that lovely historic building remains the home of the Bremen Bank.

This clipping is interesting because its caption tells the story of what has happened to large buildings built for specific large tenants when the original tenant moves out. First another large user might come along, with a less prominent use of the space (her, a real estate office). Then comes a second wave of office use, and further depreciation of value. Finally, the property is eyed for a larger development. The story here ends a few months after this blurb appeared in the newspaper. After Mallinckrodt purchased the lovely old bank building, it wrecked it. While the blurb mentions federally-subsidized atomic energy activity, Mallinckrodt actually wrecked the Bremen Bank for a worker parking lot. To this day, the site remains vacant save a small building built on the east end if the parcel in 1994.

In 1949, such industrial expansion along Broadway north and south of downtown was not uncommon. Such expansion came on the heels of the 1947 city Comprehensive Plan, which streamlined land uses to industrial in formerly mixed-use areas along the riverfront while calling for a zoning plan that would allow such anti-urban uses as surface parking on a major thoroughfare. Alas, that zoning plan remains in place, while the land use plan finally changed in 2005. Also remaining is the notion that industrial sites need to spread outward, surrounded by parking and open land, and not be more integrated into city neighborhoods. A clipping like this demonstrates that there are formidable constants in historic preservation and urban design. Nearly sixty years later, a lot remains the same.

North Broadway around Bremen Bank, however, does not remain the same. Mallinckrodt’s expansion — much of it for parking — erased most of the pedestrian quality of that street scape. Besides the bank, only a few other small businesses are open there. Interstate 70 forms a barrier between this area and the populated section of the Hyde Park Park neighborhood to the west. The city government officially draws the Old North and Hyde Park boundaries at I-70, further enforcing the separation. Had things progressed differently, the old Bremen Bank could have been retained along with other buildings on Broadway, with Hyde Park connected to its major employer and to the riverfront.

What is puzzling is that at the same time the 1947 Comprehensive Plan’s call for creating an industrial wall along the river was being drafted, civic leaders were also plotting the construction of the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial downtown in order to improve the central riverfront. Did no one see the conflict between the policies? There was already an organic urban connection to the river, and it could have been enhanced as the city began its loss of industry. Industrial expansion policies — and, I should point out, the Memorial itself — decimated the street grids, neighborhoods and buildings that bound the city to the Mississippi. The long-term consequences of the old policies are haunting us today. And we don’t have as many resources like the Bremen Bank building around to help reconnect us to the riverfront as we started with.

by Michael R. Allen

This morning, I attended a meeting where Alderman Freeman Bosley, Sr. (D-3rd) pledged to never support another demolition in Hyde Park again. Historic buildings’ value will surely increase, reasoned the alderman, “even the ones with only one wall left.” On the way back, I passed a Hyde Park house that nearly matches the alderman’s welcome remarks.

This morning, I attended a meeting where Alderman Freeman Bosley, Sr. (D-3rd) pledged to never support another demolition in Hyde Park again. Historic buildings’ value will surely increase, reasoned the alderman, “even the ones with only one wall left.” On the way back, I passed a Hyde Park house that nearly matches the alderman’s welcome remarks.

The frame house at 2911 N. Florissant Avenue is, to put it mildly, derelict. The rear half of the house has collapsed and the front has a severe lean. Owned by the city’s Land Reutilization Authority and vacant since 1996, the house has reached a point where demolition — either by condemnation or simple collapse — is a foregone conclusion.

That conclusion is sad, because the house itself is quite a unique specimen of that peculiar house type known as the flounder house. Historians have only found the flounder house form in St. Louis and parts of eastern Virginia. The origin of the flounder house is unknown, but the form is easy to spot: the roof slopes sharply from one side of the building to the other. The form garnered its name because the roof pitch made the house look like half of the head of a flounder fish.

In St. Louis, there are probably less than 30 flounder houses left. Most are small one-and-a-half-story homes, but a few are two-and-a-half stories tall. Benton Park, Gravois Park, Marine Villa, Soulard, Old North St. Louis, St. Louis Place and Hyde Park all have flounder houses. The noteworthy thing is that, of all of the examples that are known to survive, the house on North Florissant is the only frame flounder house. While others may exist, perhaps altered beyond recognition, none have been identified by historians at the Cultural Resources Office or Landmarks Association of St. Louis. The house in Hyde Park is quite unique.

Another interesting element to the house is that the side walls of the foundation seems to consist of two wooden sills spaced by a fachwerk wall atop a shallow rubble stone base. Fachwerk is essentially the use of covered masonry to fill in spaces between studs. Outside, a fachwerk wall looks like clapboard, timbered stucco or whatever cladding conceals it. This foundation’s original cladding and masonry are gone, with concrete block and weatherboard substituted.

Another interesting element to the house is that the side walls of the foundation seems to consist of two wooden sills spaced by a fachwerk wall atop a shallow rubble stone base. Fachwerk is essentially the use of covered masonry to fill in spaces between studs. Outside, a fachwerk wall looks like clapboard, timbered stucco or whatever cladding conceals it. This foundation’s original cladding and masonry are gone, with concrete block and weatherboard substituted.

Alas, being a badly-deteriorated frame building in Hyde Park does not distinguish the house. Hyde Park has many ailing frame structures that are worthy of preservation. Most are in better shape than the flounder house.

Alas, being a badly-deteriorated frame building in Hyde Park does not distinguish the house. Hyde Park has many ailing frame structures that are worthy of preservation. Most are in better shape than the flounder house.

by Michael R. Allen

The St. Louis Preservation Board meets Monday at 4:00 p.m. at the offices of the Planning and Urban Design Agency on the twelfth floor of 1015 Locust Street. Meetings typically last three hours.

Here are some highlights from the agenda:

Preliminary Reviews

5594 Bartmer Avenue: The proposed demolition of a beautiful and rare Shingle Style house appeared on the Preservation Board agenda two months ago and was deferred pending study of the reuse potential by the staff of the Cultural Resources Office. Staff has written an excellent report on the building condition and reuse feasibility based on a thorough site visit; read that here. Staff recommends denial of the permit and exploration of a National Historic District for Bartmer Avenue. This house and its neighbors fall outside of any historic districts that would enable the use of historic rehabilitation tax credits.

2300 Newhouse Avenue: The proposed new construction of six frame homes with attached garages in the western edge of Hyde Park manages to add yet another absurd faux historic design to the architecturally mongrelized neighborhood. Here we have brick fronts with shaped parapets imitating 20th century buildings that can be found in Hyde Park, but there is a twist: the parapets are actually gable ends on a front-gabled building! The sides and rear show the pitched roof and reveal the illusion the front barely conceals. Furthermore, the developer includes attached garages and has not submitted a site plan showing setbacks. Staff recommends denial as proposed.

Appeals of Staff Denials

5286 Page Avenue: The appeal of staff denial of a demolition permit for the two-story commercial building at the southeast corner of Page and Union has been on the agenda for months, always being continued at the request of the owners. Another continuance is possible. The building is a contributing resource to the Mount Cabanne/Raymond Place National Historic District and the last remaining commercial building at a prominent intersection degraded by a Walgreens across the street. Staff urges upholding their denial.

4218 Maryland: The unlawful alterations made to this house transformed it in disturbing ways: rebuilt bizarre porch, new cheap door and sidelights that don’t even fit the opening, alteration of brick pattern and color on front elevation and removal of two front bay windows and replacement with flat openings. Yikes! Staff recommends upholding their denial.

Appeal of Preservation Board Denial

2013-15 Park Avenue: The builder of infill housing in Lafayette Square wants to amend earlier plans to face the side elevations with brick and instead face them with vinyl siding. Staff recommends upholding their denial of this request, and wisely so. Here we have strong neighborhood support for a strict local historic district ordinance that expressly prohibits sided primary and secondary elevations. One expects Lafayette Square to be the last local district where vinyl siding should be approved; the neighborhood is both bellwether and inspiration for the power of local district ordinances to shape attractive neighborhoods. (The Lafayette Square standards can also be an example of the the blind spots of such ordinances, but not regarding the use of vinyl siding.)

by Michael R. Allen

Developer Paul J. McKee, Jr. may speak about his acquisitions in north St. Louis in public next Thursday, October 25 at Holy Trinity Church in Hyde Park. McKee is an invited guest to the next regular public meeting of Metropolitan Congregations United (MCU), the interdenominational Christian alliance formed to promote social justice and high quality of life for the region’s urban core. According to MCU members, if he appears, McKee will state his agreement to a number of conditions MCU has set for their endorsement of his plans for north St. Louis.

While McKee’s willingness to make a public appearance is laudable — and some might say is an appropriate response to recent criticism of his silence — the fact is that the meeting is not a public forum intended to expose affected north side residents to the developers whose plans have altered their neighborhoods.

Given the format of MCU’s public meetings, a reasonable expectation is that McKee will make a brief statement of his intention and why he needs MCU support. A representative from MCU will list their conditions for support, which had been agreed upon by McKee and MCU prior to the meeting. McKee will state that he will abide by the four standard MCU conditions for supporting development: respect for urban character, not displacing people, affordable housing, and community participation.

Hence, the format does not allow McKee to present any substantial information. He will not be taking questions, or listening to comments. The audience will be composed mostly of MCU members, with a smattering of any near north side residents who manage to learn about the event and bother to attend. Residents whose homes are within McKee’s project area had a greater chance for engagement at the public meeting hosted by elected officials on August 30 at Vashon High School. McKee is not coming to the north side to address residents; he is coming to symbolically accept the political support of the influential MCU. Residents of north St. Louis will have to keep waiting for a meeting with McKee that is truly public.

In the meantime, perhaps MCU can consider the message sent by endorsing plans with details are unknown to the residents of the areas the plans affected; with an acquisition program fraught with allegations of fraud and deception; that has created nuisance properties on healthy blocks, driven down property values and led to displacement of poor residents; and that has created a climate of uncertainty and resignation in an area showing strong signs of revival. Does it not bother MCU leaders to endorse a development plan long before people affected by it eren know what it is?

MCU missed the chance to hold out their endorsement until McKee gave affected residents a chance for real dialog. Instead, MCU is stepping over residents of Old North St. Louis, St. Louis Place and JeffVanderLou. Hopefully McKee won’t do the same, and will meet directly with residents.