by Michael R. Allen

Demonstrating against the San Luis demolition, June 2009.

Tomorrow at 11:00 a.m., the Eastern District of the Missouri Court of Appeals hears oral arguments in Friends of the San Luis v. the Archdiocese of St. Louis. The court meets on the third floor of the Old Post Office downtown, and supporters of the Friends of the San Luis are invited to attend. The Court of Appeals will issue its ruling later.

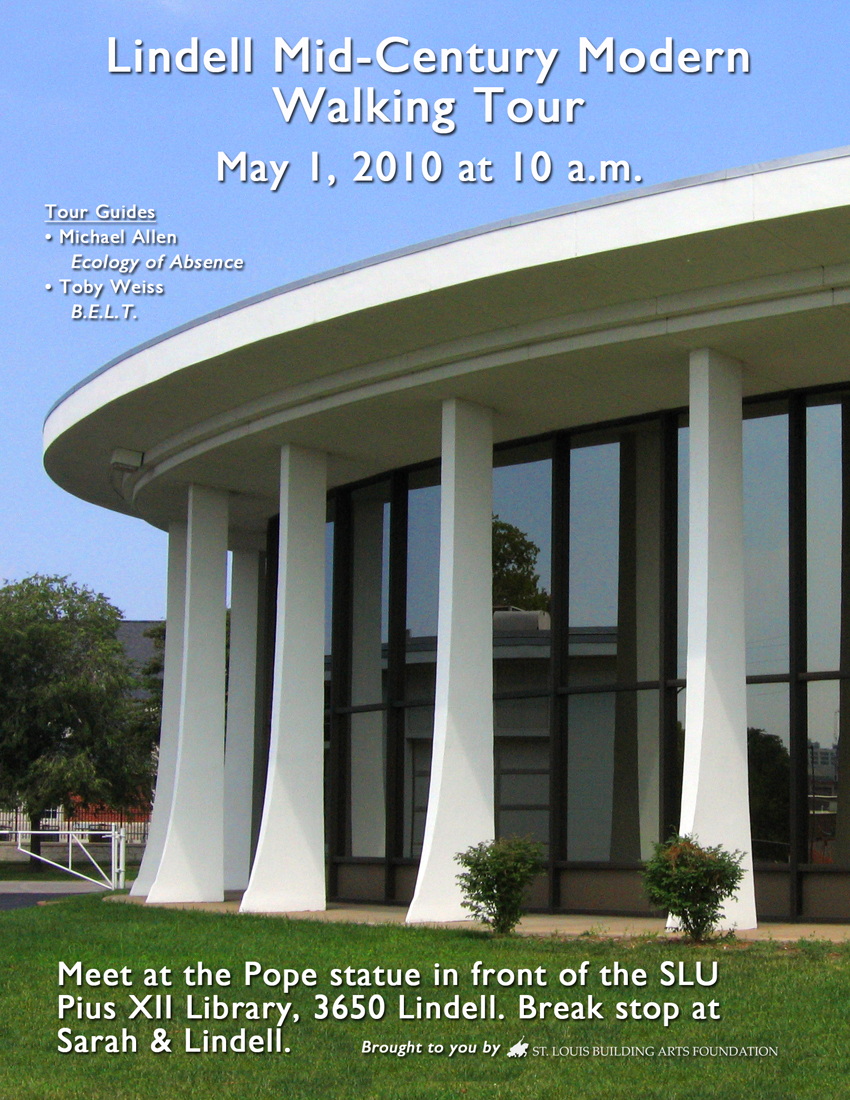

What is happening? After the Preservation Board approved by a thin 3-2 margin a preliminary application for demolition in June 2009, the Friends of the San Luis (disclaimer: I serve as the organization’s president) filed a petition for injunction to halt the demolition of the mid-century modern San Luis Apartments (originally the DeVille Motor Hotel) 1t 4483 Lindell Boulevard in the Central West End. Under city preservation law, a preliminary grant of demolition cannot be appealed until a demolition permit is issued. That stipulation makes appeals moot, at least beyond procedural review.

Circuit Court Judge Robert Dierker, Jr. dismissed the Friends’ petition with prejudice. Dierker opined that preservation laws were an encumbrance on private property rights, and that only persons with direct financial interest — essentially, adjacent property owners — have standing under the city’s preservation ordinance. (Dierker’s forthcoming ruling in the Northside Regeneration suit should be interesting given that he must choose between the divergent interests of private property owners.) The ruling cut against city government’s own interpretation of the ordinance by granting only narrow right to redress.

Given Dierker’s conservative judicial activism, the Friends could have let the matter go. Yet we appealed to ensure that Dierker’s ruling does not stand as precedent in the future. Who knows when and why citizens will need rights to appeal the Preservation Board’s decisions? All we know is that the right to appeal should apply to any citizen of the city of St. Louis. After all, the ordinance states that “[t]he intent of this ordinance is to promote the prosperity and general welfare of the public, including particularly the educational and cultural welfare.”