While we were writing the building description of this two-flat in the proposed Fairground Park Historic District in the O’Fallon neighborhood, we did a double-take. Is that…? Yes, that is. An owner of this striking building at 4147 W. Kossuth Avenue, built in 1916 by contractor J.W. Jones, covered the open false gable end in mesh to keep birds out. The neighboring building to the west has an identical feature, open, and seems clean. the two buildings to the east have identical features closed-in. So it goes.

Category: North St. Louis

by Michael R. Allen

In The Power of Place, Dolores Hayden champions the study and preservation of common urban vernacular housing as the best way to record the lives of most Americans. “Most can be learned from urban building types that the represent the conditions of thousands or millions of people,” Hayden writes. Yet Hayden finds that scholars are more interested in simpler rural and exotic urban types (the mythic flounder house is our local intrigue-builder). To some scholars, Hayden observes, “the best vernacular building will always be the purest, the best preserved or the most elaborate example of its physical type.”

Hayden’s observations can be counterbalanced by emergent material culture studies that widen the architectural history of cities beyond the showiest (prettiest?) vernacular buildings and those whose owners seek official landmark or National Register status (regulatory vehicles that enhance but do not replace cultural appreciation). Objectification of domestic architecture is far simpler using pure examples — we who practice architectural history can then shift the focus onto style, form and material so as to avoid messier discussions of class, race, use, power and alteration. Yet much housing production historically in St. Louis and other cities came through mass building practice. One of those practices was alteration by later, lower-income owners often strapped for cash and in search of a cheap fix.

by Michael R. Allen

A distinctive building in the northern reaches of The Ville is no more. In late August, the city wrecked the two-story, mansard-atop-brick mass at 4159 Ashland Avenue. This strange specimen sat on the sidewalk line on a block where remaining buildings — fewer in number than ever — maintain a general setback of ten feet, and are residential. This building had traces of a storefront opening (see the painted, nearly-concealed I-beam above a new entrance at left) suggesting a commercial past.

by Michael R. Allen

Although heavily deteriorated, and possessed by a shadowy real estate speculator, the lonely large residence at the southwest corner of Cook and Whittier avenues remains a stunning example of local Richardsonian Romanesque residential design. The house was built around 1892, with its definite architect a mystery and its origin enmeshed in a design exercise whose details are also elusive. Underneath a high-pitched slate-clad hipped roof with dormers is a two-story brick building on raised basement. A curious corner bow is open at the second story, framed by Iowa sandstone elements and rising to an intersecting rounded hip.

Today the St. Louis Preservation Board will consider recommending approval of the National Register of Historic Places nomination for the O’Fallon Park Historic District. This meeting is the first step toward listing the historic neighborhood in the National Register. After today, the nomination heads to the biggest step: consideration by the Missouri Advisory Council of Historic Preservation at its next public meeting on August 17.

View O’Fallon Park Historic District in a larger map

If the Advisory Council approves the nomination, it will be sent to the National Park Service for final listing. Depending on the length of that consideration, the O’Fallon Park Historic District might be listed in the National Register of Historic Places by the end of October. State and federal historic rehabilitation tax credits would be available immediately.

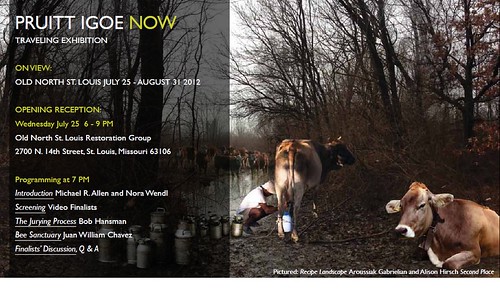

Pruitt Igoe Now Exhibition Opening

Wednesday, July 25 from 6:00 until 9:00 p.m.

Old North St. Louis Restoration Group Gallery, 2700 N. 14th Street (at Montgomery)

The Old North St. Louis Restoration Group hosts the first exhibition presenting the winner and 31 finalists in Pruitt Igoe Now, an ideas competition that examined the future of the 33-acre forested vacant site of the former housing project. Entrants in Pruitt Igoe Now came from a wide variety of disciplines and explored futures that included design intervention, urban redevelopment, agriculture, cultural memorialization and forest management. The program includes remarks from Bob Hansman, Associate Professor of Architecture at Washington University in St. Louis and a competition juror, artist and cultural activist Juan William Chavez, creator of the Pruitt-Igoe Bee Sanctuary, Michael Allen, Director of the Preservation Research Office and competition manager, Nora Wendl, Assistant Professor of Architecture at Portland State University and finalists in the competition.

(Preservation Research Office provided pro bono staffing for Pruitt Igoe Now. Alyssa J. Stein, intern, deserves many thanks for her work on the competition.)

NORTHSIDE WORKSHOP AFTER PARTY

The Northside Workshop, located at 1306 St. Louis Avenue on the same block as the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group, will be open from 9:00 p.m. until 11:00 p.m. with an after party following the exhibit opening. There will be music, refreshments and tours of the north side’s newest art space.

by Michael R. Allen

On June 25, the Pruitt Igoe Now design competition (staffed by the Preservation Research Office) announced its three winners, selected from its thirty-one finalists. The scope of the initial 346 submissions that envisions a new life for the 33 vacant, forested acres of the Pruitt-Igoe site included many submissions that examined the preponderance of vacant land around the site. These submissions generally tended to look at the southern end of the St. Louis Place neighborhood, just across Cass Avenue from the site, or the eastern end of JeffVanderLou, just across Jefferson.

One of the competition finalists, a video submission entitled “LandRun,” whimsically suggests that the vacant land in and around Pruitt-Igoe be opened to development via an annual “land run” reminiscent of the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889. That event brought sudden and frenetic development, with the cities of Guthrie and Oklahoma City ending up with over 10,000 residents in one day. The impetus for settlement was the availability of plentiful undeveloped publicly-held land. North St. Louis around Cass and Jefferson remains partially settled, and has been settled through urbanization in the 19th century, but it now has vast acres of unused land. (Admittedly much of what was publicly-owned land when Pruitt Igoe Now opened in 2011 is now owned by one developer, Northside Regeneration LLC.)

“LandRun” envisions a lively and diverse re-settlement effort, and casts its prediction toward hand-tended agriculture instead of dense urban development. With the North Side Regeneration project in the area, there won’t be a land run in the area around the Pruitt-Igoe site. Yet other parts of the city, and East St. Louis, have tracts of non-taxed land currently costing local government money to maintain. Large-scale redevelopment has proven to be a perpetual myth whose pursuit only drains tax dollars and population. The 1889 land run divested the federal government of the costs of long-term land ownership while stimulating economic development and tax revenues. Could St. Louis dream of doing the same through a Land Reutilization Land Run?

“LandRun” was created by Julien Domingue, student in architecture, ENSA – Paris Belleville, Paris; Bernardo Robles Hidalgo; student in architecture, ENSA – Paris Belleville, Paris; Camille Lemeunier; student in architecture, ENSA – Paris Belleville, Paris; Laetitia Anding-Malandin; student in applied arts, visual communication, DSAA Jacques Prévert, Paris.

by Michael R. Allen

Over the weekend, several friends alerted my attention to a rather naive essay in the Daily Mail showing “abandoned” St. Louis buildings. Two of these friends own one of the houses depicted in the arresting images by Demond Meek thay provoked the articles, entitled “City of ghosts: Haunting abandoned buildings of St Louis after the city’s population FELL by 70 per cent in a century”. These friends are rehabbing a small house in Old North St. Louis that may seem neglected to a passer-by lacking the local knowledge that helps differentiate the holdings of slumlords and city agencies from the hopeful projects of urban caretakers.

The Daily Mail article makes a generic argument about St. Louis not caring about its beautiful buildings, but its reporter chose the wrong photographs to make that point. The first image used shows a building in the 1500 block of Palm Avenue owned by the city’s Land Reutilization Authority, but available for rehab through a partnership between LRA and the Old North St. Louis Restoration Group. The second photograph depicts the massive Second Empire Loler Residence at 2135-37 St. Louis Avenue in St. Louis Place, dating to 1871 and definitely in need of care. Yet that need is partially addressed by a new historic district designation for St. Louis Place that makes rehabilitation tax credits available for the house.

The other houses include my friends’ “cottage”, a few buildings owned by Northside Regeneration LLC — which now apparently is studying rehabilitation of many buildings — a foreclosure or two, some LRA-owned houses and even one house on Chambers Avenue in Old North that is occupied. I wonder whether an the residents of that house have seen the essay and what they would make of being included in an international chronicle of the ravages of abandonment. Whoever they are, their presence is keeping that building off of the list of endangered north side homes.

A few years ago, the New York Times used a photograph of Old North St. Louis to demonstrate the ravages of abandonment in this city. Oops. The photograph that august paper chose for its urban-decay-in-St. Louis article showed a historic two-story house at the corner of Monroe and 13th streets. Today, that house has been stabilized and made ready for rehabilitation by the Old North St. Louis Restoration group using a grant from a large national bank. Oops, again.

I doubt that the Daily Mail will follow up on its article, but if it does it should look again. Behind some of the buildings in this weekend’s articles are people who care about the future of the buildings depicted. Their stories would add some complexity to the supposed ruins, and some sense of moral urgency. Perhaps readers in London can afford to sublimate the gaze upon vacant St. Louis buildings, but St. Louisans cannot — and, largely, do not. The real story, underreported even locally, is that people do care about these buildings.

by Michael R. Allen

The Hodgen School rose from the good soil of St. Louis in stages starting in 1884. Then, 128 years later, the St. Louis Public Schools destroyed it. The Hodgen School displayed no signs of stress, decay or lack of reuse potential. Its limestone foundation and brick walls were sturdy, and its ornamental details — carved limestone blocks, rounded bows, sheet metal cornices — all were proof of the prowess of St. Louis craftsmen during the Gilded Age.

Do the blows dealt by the demolition team’s sledge hammers match the precise gestures by stonemasons long ago? Of course not. Yet they exemplify the change in attitude from the era in which St. Louis’ aspirations were palpable in the designs of architects like Otto Wilhelmi, who designed Hodgen’s main section. Today, as Hodgen School falls to create playground space serving an underwhelming replacement building, we can see this city’s casual disregard for its own future. The St. Louis Public Schools’ choice to use funds raised by the sales tax for building renovations is a travesty.

The underutilized park wast of the new Hodgen could have accommodated a playground. The old Hodgen building was deemed eligible for listing in the National Register of Historic Places by the State Historic Preservation Office last year, based on an eligibility assessment prepared by Lindsey Derrington of Preservation Research Office. National Register listing would have allowed historic rehabilitation tax credits to be used for reuse. The building’s views of the Gateway Arch and near south side location made it a likely — if not immediate — candidate for reuse. Sustainability — embodied by reusing second-nature resources that include whole buildings — ought to be a value that the St. Louis Public Schools teaches its students.

The Special Administrative Board raised $150 million for building improvements through Proposition S in August 2010. Voters did not know that any of this money would be used to demolish a historic, National Register-eligible building — a use that does nothing to help education in a struggling school district. The district instead could have raised money by selling Hodgen School, which taxpayers had already renovated at a cost over a half million dollars around 1990. The Special Administrative Board not only wasted money today, they wasted money spent 22 years ago. Yet St. Louis is not alone, which is why statewide advocacy group Missouri Preservation categorically placed School Buildings of Missouri on this year’s statewide Most Endangered Places List. That listing and the Hodgen demolition should make St. Louisans mindful of what built record of our values we are giving to the next generations.

by Michael R. Allen

Today the Missouri Court of Appeals filed its ruling in Northside Regeneration and the City of St. Louis’ appeal of Circuit Court Judge Robert Dierker’s July 2010 ruling that suspended the redevelopment ordinances for Northside Regeneration’s redevelopment project. Rather than affirm the lower court’s ruling, the Court of Appeals stated that it would affirm the ruling but is instead sending it to the Missouri Supreme Court due to “due to the general interest or importance of questions involved.”

One of those fundamental questions is whether Missouri’s statues on tax increment financing (TIF) permit a municipal government to designate a tax increment financing plan for an area for which a developer has not provided specific redevelopment goals. Northside Regeneration has claimed that a redevelopment agreement for a small part of the larger 1,500 acre project satisfies Dierker’s identification of defects in the TIF and redevelopment ordinances. The Court of Appeals disagrees.

Notably, no citizens have challenged that separate redevelopment ordinance for several discrete projects within a smaller area. Should the developer want to pursue separate ordinances for smaller projects across the rest of the larger area it seeks to redevelop, there is not likely to be serious opposition. In the two years since Dierker’s ruling, Northside Regeneration has been able to acquire city-owned land in its project area, complete the rehabilitation of a warehouse on Delmar Boulevard and continue to pursue development goals. Northside Regneration’s ambitions remain large, but its operational scale has adjusted. The new scale is far less threatening to the urban fabric of the north side than it was during the acquisition phase, when entire blocks of buildings and people disappeared regularly.

The only facet of the project that has been obstructed is access to the $398 million TIF that the Board of Aldermen authorized in 2009. Dierker’s ruling does not preclude the passage of smaller TIF ordinances within the project. By the time the Missouri Supreme Court hears Northside Regeneration’s appeal, the developer may even have completed more projects in the area. What critics stated early on — that the project would have its greatest success block by block, project by project — will have become a deep reality for Northside Regeneration. Even the developer’s own approach, which has been lacking in the early fanfare and focused on obtainable work, reflects that. The 2009 ordinances are effectively dead at this point, and everyone knows it.