by Lindsey Derrington

Saint Louis University recently stated that it has “studied the Pevely buildings extensively and determined they [do] not meet the needs of a modern health care facility,” effectively justifying its proposed demolition of the entire National Register-listed complex at Grand and Chouteau avenues for a new doctor’s building. Yet the original 1915 Pevely corner building and 1943 Pevely smokestack — the two structures the Pevely Preservation Coalition seeks to preserve — occupy a mere sliver of the university’s nearly 10 acre site between Grand and Chouteau Avenues and 39th and Rutger Streets. This begs the question: “Why?”

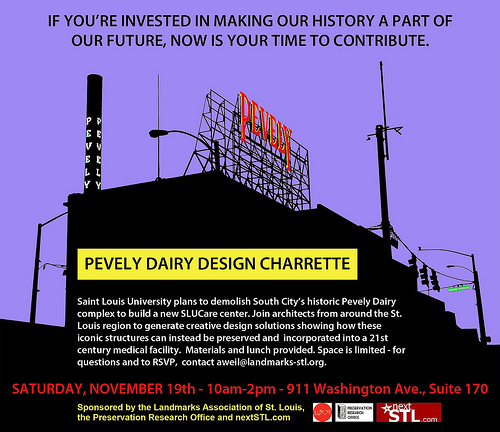

This past Saturday, November 19, the Preservation Research Office, Landmarks Association of St. Louis and nextSTL took on this question with the Pevely Dairy Design Charrette. The four hour charrette proved an incredibly positive event aimed at finding practical solutions for the university to incorporate these historic buildings into its medical campus. The event far exceeded our expectations, with a pool of sixteen diverse participants consisting of architects, graduate students from SLU’s urban planning program, a mechanical engineer, and even a SLU doctor weighing in.

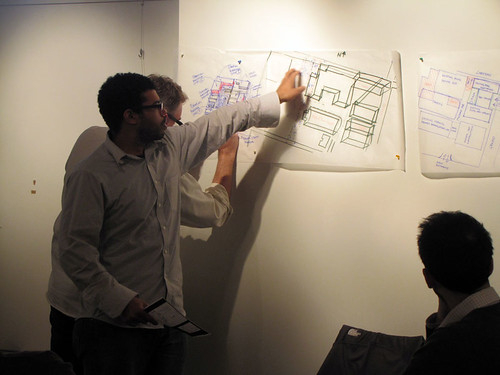

After a thorough discussion of the site’s dimensions, SLU’s extensive landholdings in the area, and the university’s probable needs, participants subdivided into four groups. Each focused on a different approach, including converting the corner building into doctors’ offices with a larger modern addition, adapting it into market-rate housing and ancillary facilities for the medical school, finding additional on-site locations for new buildings, and generating an overall site plan to connect this corner to the rest of the university.

The charrette was characterized by the matter-of-fact study that its designers bring to the workplace and classroom on a regular basis. Idealistic, or even hopeful rhetoric was wholly absent, because it turns out that this design “problem” is no problem at all. Each group presented multiple scenarios of how to preserve these buildings while still accommodating the university’s needs. The take-away was that the task is almost too easy, and that given more time, even more solutions could be found.

Their plans will be presented at the Preservation Board meeting on Monday, November 28. Hopefully board members will see past SLU’s influence and political clout to what is so clearly apparent: these structures can and should be incorporated into the university’s larger medical campus to serve patients, doctors, and students in a manner that enhances the built environment rather than destroys it.