by Michael R. Allen

Last week I participated in two gatherings held consecutively in St. Louis’ kindred city, Philadelphia: the Reclaiming Vacant Properties Conference, hosted by the Center for Community Progress, and the Right Size, Right Place Forum hosted by the emergent Preservation Rightsizing Network. While I was a session moderator and presenter, respectively, I would have attended each of these events regardless. The preservationist impulse of my younger career has hit head-on the realization that historic district creation, demolition protest and the fabled building “mothballing” are transitory tools at best — not options that resolve vacancy and threats, but stabs at creating possibilities. The hard work lies within those possibilities.

The first challenge remains framing the term “rightsizing.” Our panel took aim at the prevalent and oversimplified connotation that “rightsizing” means demolition of supposed liability properties. Perhaps we erred in our offensive, as we received very intelligent critique reminding the panel that “right size†need not be restricted to subtractive activities. Indeed, “right-sizing†can also refer to infill projects that add density to stable neighborhoods, renovation of historic buildings that add new residents or businesses, interim or permanent uses for vacant lots, and the creation of historic districts to guide policy-making. The “right size†of every American city is not necessarily smaller. However, much of the discussion on “rightsizing” (or “managed decline,” or “shrinking cities”) nearly obsesses over population loss and resource scarcity, without being more accurate about the complexity of planning in what are more accurately called changing rather than shrinking cities.

Thus, the realm of Reclaiming Vacant Properties might seem to be foreign soil for the preservationist, and there were but a handful of us practitioners amid the critical mass of landbank professionals, planners and community development folks. Yet the opening plenary showed a wider recognition that existing buildings are assets than some might expect. A panel of mayors from South Bend, Gary, Cincinnati, Philadelphia and Allenton — company St. Louis should embrace, not shun — turned up some interesting comments by Cincinnati Mayor Mark Mallory. Mallory admitted that he personally joins a city staffer on drives to look at each building on the city’s demolition lists. The mayor then makes his recommendations for demolition to the city. Mallory explained that he doesn’t want demolition to create holes in viable blocks, lowering property values and removing potential city revenue and population.

Still, a questioner at the end of the plenary posed the oft-stated opinion that rehabilitation of historic buildings is usually more expensive than new construction, a false dichotomy. The dichotomy that is more likely in cities with significant vacancy is the gap between a renovated historic building and a long-term vacant lot. The question underscored that the language of historic preservation has yet to reach many people working in community development. Yet the panel that I moderated, “Building on Historic Assets,’ attracted over 60 people even put up against the Detroit Future City panel. There is an intersection of interest when preservation practitioners show up in unlikely places.

Our challenge in the right-sizing world is posing historic preservation as practice, specialized knowledge about place that is as essentially to good planning as the knowledge brought by tax foreclosure experts, architects and urban planners. Yet our key values should not be diluted in the process. As Advisory Council on Historic Preservation member Brad White stated on our panel at Reclaiming Vacant Cities, the message is not even that historic buildings have value, it’s that buildings have value. Period. Buildings have economic value, social value, artistic value and ecological value. All of these are traits that planners tout with new green space projects, affordable housing developments, downtown retail, and other endeavors based on new construction. How do we remind people that existing buildings offer every bit of the value of new buildings, with the added values of energy conserved by already being built, and material quality that this country will never see again?

Two preservation professionals who are working on strategies for asset-based “right size” planning are Donovan Rypkema and Cara Bertron at PlaceEconomics. The PlaceEconomics Rightsizing Cities Initiative promotes “planning decisions and regenerative opportunities that are deeply rooted in local landscapes and character.” So far, PlaceEconomics has worked on a pilot ReLocal program in Muncie, Indiana. Although the project delves into decisions about demolition, the goal is to get planning agencies to consider the economic benefits of preservation and the costs of demolition — to look beyond policies that encourage demolition as the only blight remedy. As Rypkema often says in his frequent lectures, demolishing a building removes one option for a property — and why would cities want to narrow their options?

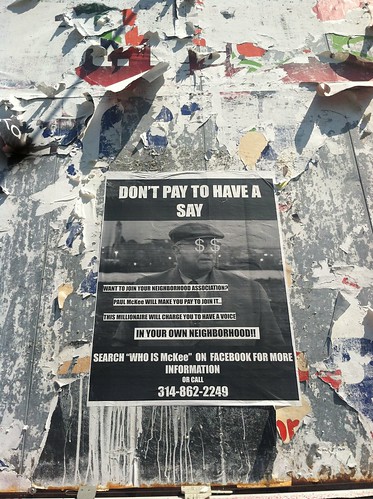

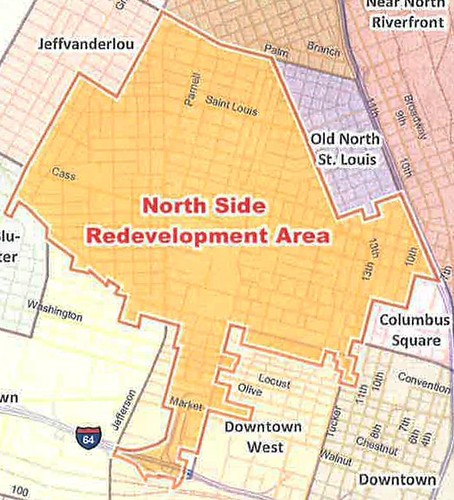

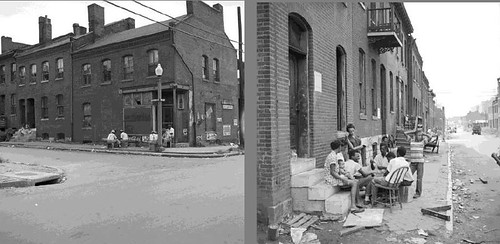

Government officials are not our only needed allies — we must reach people who live in places whose revitalization we can foresee and assist. The people who live in neighborhoods affected by right-size initiatives, or just large housing or redevelopment projects, are predominantly poor and in many cases largely African-American. The historic preservation movement has never done well at reaching out to these groups, in some cases because we aren’t listening. I work with urban preservation groups in St. Louis and other cities, and none have more than a few African-Americans on their boards or staffs. Poor people aren’t represented at all. If we are going to help right-size cities, we have to realize that cities are collections of people before they are collections of buildings — and we are going to have to treat urban neighborhoods as something other than the frontiers we seek to intellectually colonize.

Building real alliances in distressed neighborhoods will entail listening, building more inclusive leadership structures on preservation campaigns and within preservation organizations. We need to shed some of our old skin. Many preservation battles don’t involve demolition — they involve keeping homeowners and renters in their homes, so buildings don’t go vacant. Foreclosure mediation, home repair, eminent domain resistance, mediation with code compliance are all aspects of preservation work that historic preservationists need to get better at. Communities typically welcome practitioners who offer resources for them. We have to develop capacity to provide those resources, and then remember that they are in service to the real ground-level leaders.

Preservation practitioners have the chance to help define “rightsizing,” and through that process redefine urban preservation so that it is more responsive to 21st century needs and possibilities. Historic preservationists should have been talking to urban planners and residents of poor neighborhoods more often for decades. What happened in Philadelphia is just part of a larger and long-term dialogue that will place historic preservation more centrally in urban development and right-sizing — alongside disciplines that are not questioned when they claim seats at the table. We should not be shy about taking a seat, but we should make sure we are ready to collaborate, listen, and develop new methods.