by Lynn Josse

A lot of what you need to know about the Castle Ballroom can be read on its exterior. The commercial first floor of the building indicates its historic place on a busy streetcar line. Graceful double-height arched windows above the first story reveal a ballroom which extends almost from the street to the alley. The lively Renaissance Revival brickwork indicates the aspirations of the owners in 1908 — this is a proper dance academy, not a warehouse. Perhaps the most telling piece of evidence isn’t part of the building itself, but in the enormous expanse of lawn across the street. The Castle Ballroom had epitomized early 20th century elegance, but half a century later it was only spared from the nation’s largest urban renewal slum clearance project by virtue of being on the north side of Olive rather than the south side. Put all of these pieces together, and you’ve got the story.

In just over four decades of operation, the Castle Ballroom witnessed and responded to wave after wave of changing taste in music and dance. Herman Albers and Cornelius Ahern constructed the building in 1908. Architect J.D. Paulus designed the building. They had previously operated the dance academy at Cave Hall, the above-ground entertainment center associated with Uhrig’s Cave at the southwest corner of Jefferson and Washington. When the old Cave Hall was demolished to make way for the Coliseum, they took the name with them.

Mr. and Mrs. Albers and Mr. and Mrs. Ahern themselves supervised the dancing at the new hall, and the Uhrig’s Cave Orchestra followed them to the new location. By this time, traditional tastes in music were giving way to a new sensation — ragtime. The syncopated rhythms of the ragtime music invited a daringly different style of dancing. Scandalous new “animal dances” (the Turkey Trot, Bunny Hug, and Grizzly Bear, among others) were popularized at the highest levels of society. In 1911, Chief of Police William Young instituted a Morality Squad to inspect public dance halls and stop the vulgar new dances wherever they occurred. Newspapers gleefully covered the controversy, their condemnations illustrated with titillating line drawings of couples in unseemly poses. Alexander DeMenil, always a spokesman for Victorian values in the Edwardian age, wrote that the dances were a symptom of society’s decadence. “We do today openly and publicly what we would have been ashamed to do in secret ten years ago,” he wrote in 1913. “Far from being ‘new,’ these dances are a revision of the grossest practices of savage men.”

If the moralists thought the ragtime dances were bad, what came next was much, much worse. Jazz music invited even more jumping and gyration. Instructors of traditional ballroom dance banded together in self-defense, encouraging additional legislation to eradicate dances such as the “Camel Walk.” The new ordinance was designed to “reach the irresponsible dancing teachers who, because of the money there is in it, will teach any kind of wiggle.”

After his partner’s death, Albers changed the name of the venue to Castle Ballroom. In doing so, he embraced a more modern image for the academy. Vernon and Irene Castle had been the greatest names in dancing until Vernon’s death in a training accident during World War I. The Castles earned their success by taking modern dances and making them completely respectable. Today, the name “Castle” may sound like a reference to the building, but in 1922 the allusion to the famous dancers could not have been missed.

The dawn of the Jazz Age spelled the end of the great ballroom dancing academies of St. Louis. As early as 1922, dance instructor Alice Martin claimed to have “practically given up teaching ballroom dancing†because of the “vulgar extremes of these times….” By 1930, most teachers of ballroom dancing had stopped advertising. The Castle’s newspaper advertisements increasingly emphasized the hall’s availability for rental.

In 1934, Herman Albers closed the Castle and filed for personal bankruptcy. The end of Prohibition had played a role, his attorney noted, since people now danced at cafes where liquor was sold. He also blamed the widening of Olive Street and a change in streetcar stops. His comments to the Globe-Democrat overlook an obvious demographic shift in the neighborhood.

In the second and third decades of the 20th century, the immediate neighborhood of the Castle Ballroom, especially the blocks just south, had transitioned from an almost completely Caucasian neighborhood to one that was dominated by African American institutions. The fabled Mill Creek Valley neighborhood developed the city’s greatest concentration and number of black residents. When the Castle re-opened in 1935, it was advertised as “THE MILLION DOLLAR DANCE PALACE – Exclusively for the Best Colored People of St. Louis.” The hall again held dances on Tuesday, Thursday, Saturday and Sunday nights, but they were advertised to a different clientele.

Manager Jesse Johnson was frequently touted in The St. Louis Argus as the city’s top black promoter. A favorite house band was Eddie Randle’s St. Louis Blue Devils. According to one account, it was at the Castle Ballroom that the teenaged Miles Davis first auditioned for the band. With Eddie Randle (playing regularly at the Castle as well as other venues around town), the young prodigy received his first experience playing in a professional band. By the end of the 1930s, Johnson brought in more national acts, including Duke Ellington. Under other management, the entertainment included Fletcher Henderson, Ella Fitzgerald, Fats Domino, and Count Basie. Through the 1940s, the Castle featured local and national touring acts and hosted many private events for black organizations.

The early 1950s brought the Mocambo Club (named for a famous Los Angeles hot spot) This club lasted barely a month before a dispute at the bar turned into a sensational shootout which claimed the life of the owner and a local underworld figure. The Globe-Democrat reported that there were thirty people present but only one witness. When the club reopened under new management, it was still able to attract national favorites such as Louis Armstrong and the Ink Spots, both in 1952.

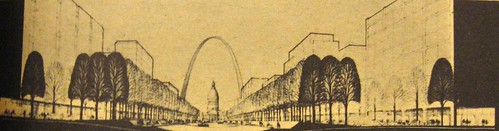

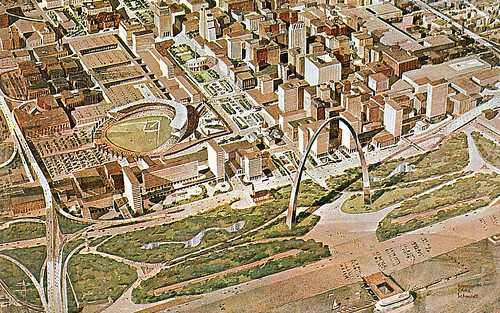

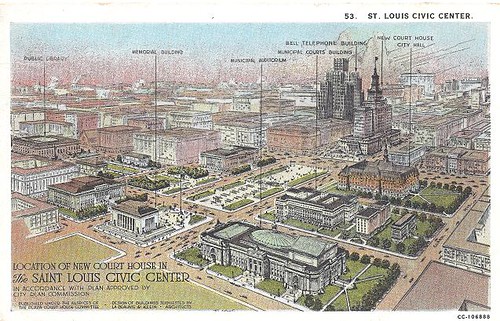

The final days of the Castle Ballroom coincided with a civic effort toward slum clearance. Mill Creek Valley at this time retained the deteriorated housing stock of the 19th century, densely packed with African Americans who were allowed few other living options. The neighborhood had a high crime rate, high infant mortality rate, and low indoor plumbing rate. One planning document described the neighborhood as “100 blocks of hopeless, rat-infested, residential slums.”

A bond issue for clearance and redevelopment failed in 1948. Amendments to federal law in 1954 allowed the Mill Creek Valley to become an urban renewal project, and voters approved matching local funding in 1955. Original plans called for 4,200 families to be relocated from a 107-block area. Roughly 2100 buildings plus accessory structures were to be demolished.

The northern boundary of the clearance area was Olive Street. Beginning in 1959, nearly every home, church, and business in Mill Creek was demolished. Thriving commercial districts, significant institutional buildings (including the Pine Street YMCA) and untold homes were knocked to rubble and sent to the landfill. The vast majority of Mill Creek residents were not resettled in the new housing that was built across from the Castle.

Today, the Castle Ballroom is one of the last buildings in the area to retain a strong association with the African American community that once surrounded it. The second story ballroom has not seen dancing since the 1950s, but now it has another chance. The building is on the market and substantial historic tax credits are available for its restoration. Several potential buyers have come forward, but none have committed yet. (If you’re interested in purchasing the building, visit the realtor’s web site at www.leighmaibes.com.) Public interest is also increasing, with recent appearances on music history tours by Michael Allen and Kevin Belford. Landmarks Association’s hard hat tour this past Saturday sold out, and a second tour is scheduled for February 4 (details here).

Our full nomination of the Castle Ballroom is on the State Historic Preservation Office web site here.