by Michael R. Allen

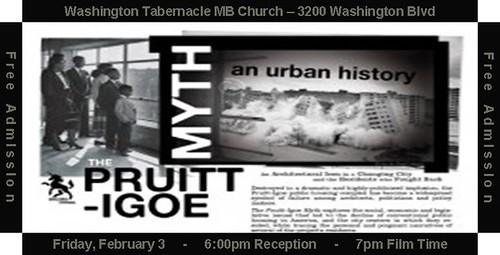

The St. Louis Development Corporation has proposed initiating a $100,000 two-year option on the 33-acre Pruitt-Igoe site for Paul J. McKee, Jr.’s Northside Regeneration LLC. During that time, the ddeveloper would have exclusive right to purchase the site for $900,000. What does this mean for the future of the site of one of the city’s most important events from the recent past?

For now, it means that the developer will be able to lay claim to the ground, and market the site as the potential location for commercial buildings. Yet the option does not stop public imagination of what could be done with the site. The Pruitt-Igoe parcel is owned by the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority, a public agency. Thus we are all owners of the site, and its future is a question of public interest. Most sites in the Northside Regeneration footprint are of marginal historic interest, but this one is rich with symbolism. What happens to Pruitt-Igoe’s remaining vacant land reflects our collective regard for the lives of all who lived in the housing project there.

Ahead of Northside Regeneration’s option, last summer I joined my collaborator Nora Wendl in launching the independent ideas competition Pruitt Igoe Now. Pruitt Igoe Now has solicited ideas and designs for the site’s reuse, and has attracted the interest of participants from around the world. We close the competition on March 16, and announce winners in late May. Our purpose is not to block redevelopment but to offer a powerful moment of civic reflection.

How do we honor the past life of the Pruitt-Igoe site through its renewal? Often historic sites connected with significant African-American experience are lost without deliberation. The list of buildings lost in Mill Creek Valley, JeffVanderLou and The Ville is staggering. The loss of public housing buildings has erased much of the postwar history of struggle and accomplishment. Pruitt-Igoe’s ruins are left as an imperfect marker of a complicated but definitive chapter in the city’s history.

WORTH READING: “Fantastic Pruitt-Igoe Design Workshop: Social Agency Lab and Neighborhood Youth” — an account of a workshop in which Hyde Park youth developed ideas for the Pruitt-Igoe site, written by a young participant.

by Michael R. Allen

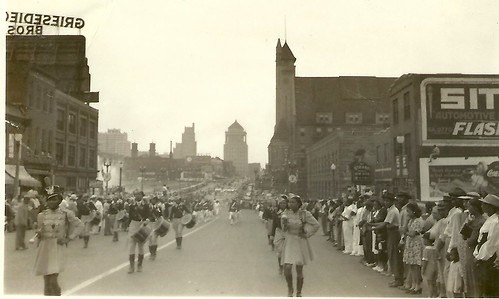

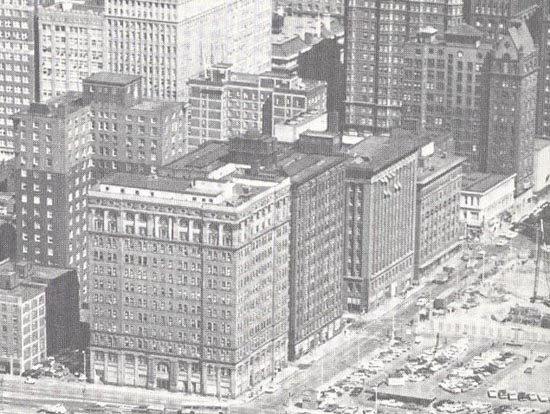

Another photograph from our collection of amateur images of the St. Louis built environment captures a parade moving westward down Market Street into Mill Creek Valley. The view was taken west of 21st street, and shows a panorama of the mid-century downtown skyline. Lacking a date, the image nonetheless offers a major clue: the surging waters of fountains around Carl Milles’ The Marriage of the Waters in Aloe Plaza can be seen at left. That installation was completed in 1940.

The image was taken before 1954, because the photograph shows blocks of vernacular, small-scale buildings between 18th and 15th streets that would be leveled for park space. Eventually this landscape would become the Gateway Mall. The buildings in the foreground would be leveled after 1959 as part of Mill Creek Valley clearance. Later, this area would be rebuilt with depressed on-ramps as part of the stalled North-South Distributor project.

Somewhere between the triumph of early intervention and later, more troubling urban renewal, a parade passed through this scene. The moment captured shows the African-American community of Mill Creek Valley in celebration, right in the heart of the city. By 1965, this community would be forever removed, and its built environment replaced by an uninspired landscape. Today city leaders have embraced the Northside Regeneration project, which calls for reconstructing the urban street grid west of Union Station and building dense infill there. Yet this photograph reminds us that architectural character is only the backdrop for urban cultural experience. Mill Creek Valley’s lively culture will never return to Market Street, and for that this city is worse.

Soulard’s Dave Lewis

Soul of Soulard from Jerry Michaud on Vimeo.

Anyone who is on the listserve of the St. Louis Rehabbers Club knows that Dave Lewis’ insights and tips on rehab work are indispensable. Those who have lived in Soulard in the last few decades no doubt know Dave’s work rehabbing his two buildings, his beautiful garden project or his assistance with countless projects of his neighbors. This video’s title suggests that Dave Lewis is the “Soul of Soulard,” a mantle (ouch) he would probably decline out of modesty. No matter; Dave’s life’s work speaks for itself.

by Michael R. Allen

This is the ninth and final part of a series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

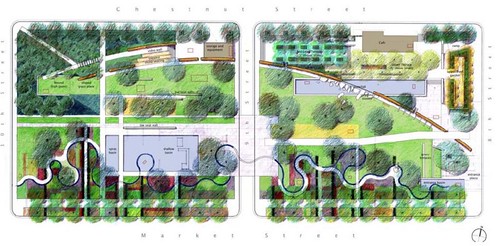

The 2007 Gateway Mall master plan provided impetus to the development of the two blocks of the mall between Eighth and Tenth streets as the successful Citygarden. Designed by Nelson Byrd Woltz architects and completed in 2009, Citygarden is an interactive sculpture garden that has garnered favorable criticism from the New York Times. Citygarden’s two blocks share the “hallway,†a wide formal tree-lined sidewalk along Market Street recommended by the new Gateway Mall Master Plan. However, the blocks eschew further strict formalism. Linear paths follow the somewhat irregular lines of long-abandoned alleys, while a gentle arc runs through both blocks. The north sides are raised up, with the eastern block containing a waterfall and minimalist cafe building on its high side and the western block rising up to a whimsical forested hill atop which is placed a sculpture. There is a plaza on the western block alive with fountain jets adjacent to a grid of large metal pedals upon one which one can jump to trigger bells at different tones. All of the sculptures can be touched. Citygarden has been so successful that the section of 10th Street between the two blocks remains closed to shield the heavy pedestrian traffic.

Citygarden’s design discarded rationalist notions of open space and view in favor of a contemporary landscape design theories of the need for activation, asymmetry, whimsy and native plantings. The small size of the intervention — two blocks — creates clear boundaries and edges of Citygarden that drive pedestrians into its space. The success of Citygarden in part comes from employing long-standing observations about the utility of basic urban design features that encourage circulation and building density.

by Michael R. Allen

This is the eighth part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

St. Louis Mayor Francis Slay and Planning and Urban Design Director Rollin Stanley announced in 2007 their intention to create a Gateway Mall Master Plan in association with landscape architect Thomas Balsley. Their plan would be the first comprehensive plan for every block that had become part of the mall, as well as the rest of Memorial Plaza. Recognizing the design failure of the Gateway Mall, Stanley envisioned a break from the past — a mall friendly to pedestrians and built around uses that attract people. Stanley and Slay went farther than most actors in this drama and admitted that the Mall needed real planning. They didn’t want to extend it or glorify it but improve it.

Unfortunately, their plan was too constrained by the old rationalist vision to be a blueprint for major improvement. For one thing, they were committed to preserving every block of the Mall as green space — a questionable proposition in a downtown with as much open space as ours. For another, their plan avoided recommendations for improving the mall’s context. The large-scaled environment around the Mall is as resistant to human action as the park itself; it’s a chicken and egg relationship and the new Master Plan acted like an ostrich.

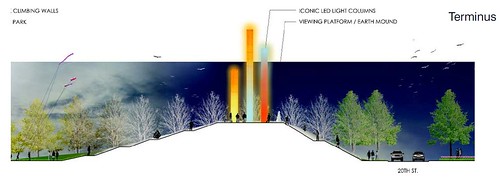

Still, there were good ideas in it. The plan avoided trying to visually unify the mall, except for a southern bike lane and promenade. The plan acknowledged the variation in block width and the curving streets that make symmetry impossible. Instead, the mall plan recommends creating different zones on the mall — a sculpture garden between Eighth and Tenth; recreation areas and a dog park west of Fifteenth street; an amphitheater-style space on Memorial Plaza; a gathering space in Kiener Plaza.

The plan tried to match these zones to adjacent uses without looking at the physical connections between. For instance, the sculpture garden introduced a rather romantic vision of human-scaled green space near downtown residences and offices. But it’s flanked to the north and south by large, monolithic office buildings set back from the sidewalk and possessing reflective windows and intrusive driveways. A walk from the north side of downtown to the sculpture garden won’t provide much delight or instruction if it passes by the bizarre sidewalk configuration on the west or east sides of the AT&T tower, for instance.

The master plan recommended more seating, a walking and running path, kinetic art on adjacent buildings, and lighting on the blocks that would make them attractive night time spaces. There was some break-down of barriers with a small restaurant building in the sculpture garden. But in some ways the restaurant and the dazzling contemporary art are low-key, updated versions of the monuments and buildings of the 1919 Public Building Group Plan.

At the Gateway Mall press conference in 2008, Mayor Slay declared a “new era” for the Gateway Mall. This era was new inasmuch as it is based on planners’ admission of the mall’s failure. However, the failure has always been systematic and structural, while the solutions outlined in the new Master Plan were topical and aesthetic. Rather than address crucial problems of identity, circulation and boundaries, the new Master Plan treated those as secondary causes by offering a remedy not to the idea of a Gateway Mall but to its execution.

by Michael R. Allen

This is the seventh part of a nine-part series on the evolution of the Gateway Mall, that ribbon of park space that runs between Market and Chestnut streets and from the Jefferson National Expansion memorial westward to Twenty-Second Street downtown. This article began its life as a lecture that I delivered to the Friends of Tower Grove Park on February 3, 2008, and was published in its entirety in the NewsLetter of the Society of Architectural Historians, Missouri Valley chapter in Spring 2011.

At the end of the 1970s, after failing to build the winning design from the 1967 design competition, city leaders did not let the dream of a “completed” Gateway Mall die. There still were blocks of old buildings to clear and new corporate high-rises to attract. However, developer Donn Lipton seized the opportunity of city inaction and in February 1977 submitted a redevelopment plan for the blocks between Seventh and Tenth streets radically different than the Sasaki plan.

by Michael R. Allen

Nearly every day I pass by this lonely two-story frame house at the northwest corner of North Florissant and Newhouse avenues in Hyde Park. While this stretch of North Florissant has its gaps, the east side is a nearly-continuous line of flats, houses and storefronts. Pietkutowski’s is not far. Yet this house stands alone at the intersection. Original weatherboard siding peaks out from failing rolled asphalt siding that mocks red brick (note the faux keystones on the front elevation!). Above, the slates on the mansard roof are in place, shedding water as they should. The side entrance is covered by a Craftsman-influenced open hood, a later addition marking stylistic changes since the nineteenth century when the house was built. Many frame houses in Hyde Park have been lost, and few have the solid and straight lines of this one. Yet I suspect one day my travels will take me past its grave-site, mud marked by bulldozer tracks.

by Michael R. Allen

On Monday, the St. Louis Post-Dispatch published an article by reporter Tim Logan that raised the issue of the city’s lack of citywide demolition review. The article, which ran on the front page above the fold, took as a starting point the sudden, lonesome death of the Avalon Theater on South Kingshighway. Since the Avalon was outside of one of the city’s preservation review districts, it bit the dust — or, rather, became dust bitten by passers-by — without any review.

Logan’s article included a promising set of quotes from two aldermen. The first came from Carol Howard (D-14th), who represents the eastern part of the Southampton neighborhood where the Avalon was located. The demolition experience has spurred Howard to seek demolition review for her ward, one of south city’s only wards that lacks review. Howard also endorses a return to citywide review, which St. Louis had before 1999. “It’s a tool, I think, that makes for better decisions,” she told Logan.

A view that could be read as dissenting came from Alderman Antonio French (D-21st), whose constituents include this writer. French’s first bill upon being elected in 2009 put the 21st Ward into preservation review for the first time since 1999. Yet the alderman wants to remove review for part of the College Hill neighborhood added to his ward in redistricting. French wants to concentrate preservation efforts on the intact largely Penrose and O’Fallon neighborhoods in his ward. “What works for Penrose and O’Fallon may not work for College Hill,” said the alderman.

Am I the only person who sees that both Alderwoman Howard and Alderman French are right? St. Louis does need citywide review, and building conservation strategies for depleted neighborhoods like College Hill — where many blocks are devoid of more than five or six historic buildings — need not entail preserving every remaining historic building.

Yet the crux of these two points’ convergence is that these decisions need to be made by qualified professional planners working in the interest of all city residents. Aldermen who serve geographic areas whose boundaries change every ten years, who lack training in urban planning and historic preservation, and who have to seek re-election are not the best people to make decisions for the long-term interests of the city’s built environment. Yet aldermen create the legislation under which review takes place, establishing guidelines that represent the public interest.

Alderman French might be suggesting that a citywide demolition review ordinance be informed by theories of planned shrinkage. Again, having professionals examining demolition seems like the best way to make that happen. Citywide review does not mean preservation of everything in the city, it means a system in which preservation planning is made under legal criteria interpreted by professionals who are free from political motivations. Applicants for demolition, aldermen, neighbors and preservationists will have a predictable public process with the same rule for every building.

If that sounds familiar, it’s what this city had before the Board of Aldermen passed the current preservation ordinance in 1999.